Why a former Vietnamese refugee returned to Hong Kong to give back to the city of her harsh childhood

- Farah Dang, 38, has been volunteering with an NGO and came back a decade ago after leaving for Britain in 1992

- She has never forgotten how others helped her, and has come to terms with her refugee identity

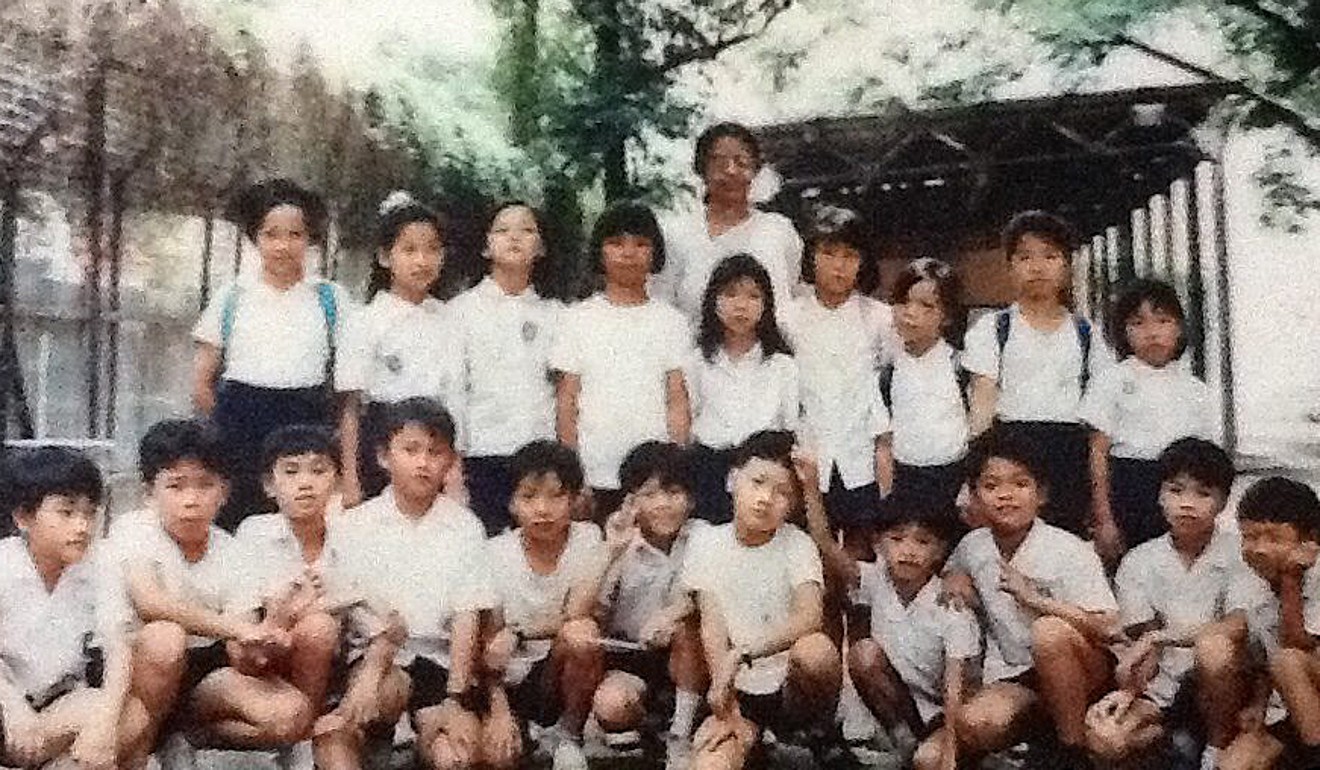

In Hong Kong’s Kowloon Bay in the 1980s, thousands of Vietnamese lived in sordid and cramped conditions in a refugee camp, sleeping among three-tier bunk beds with only tattered curtains for privacy. This was childhood for Farah Dang, now 38.

Dang was born and raised in the camp before she resettled to Britain with her family at 11.

A decade ago, she decided to move back to Hong Kong, along with her husband, and has been serving refugees whose struggles remind her of the hardship she endured.

Since 2015, Dang has been a volunteer at the Centre for Refugees in Chungking Mansions, run by Christian Action. She helps the NGO make traditional Vietnamese food for refugees seeking shelter.

“Being a refugee is never easy. I struggled with my identity for 30 years before truly opening up about it,” she says.

Dang’s parents were part of a wave of Vietnamese people who fled to the city by boat to escape communist rule following the end of the Vietnam war in 1975. Besides Hong Kong, the desperate masses spilled into Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia, creating a humanitarian crisis in the region.

According to official statistics, between 1975 and 2000, more than 213,000 Vietnamese people sought asylum in the city.

Dang’s parents are Vietnamese-Chinese and fled from the northern Vietnamese city of Haiphong to Hong Kong in 1978 amid rampant anti-Chinese sentiment in their homeland.

They stayed under appalling conditions in Kai Tak Camp, one of the city’s refugee centres and originally the base of the British Royal Air Force. The site was used to house Vietnamese refugees from 1978 till 1997.

Being a refugee is never easy. I struggled with my identity for 30 years before truly opening up about it

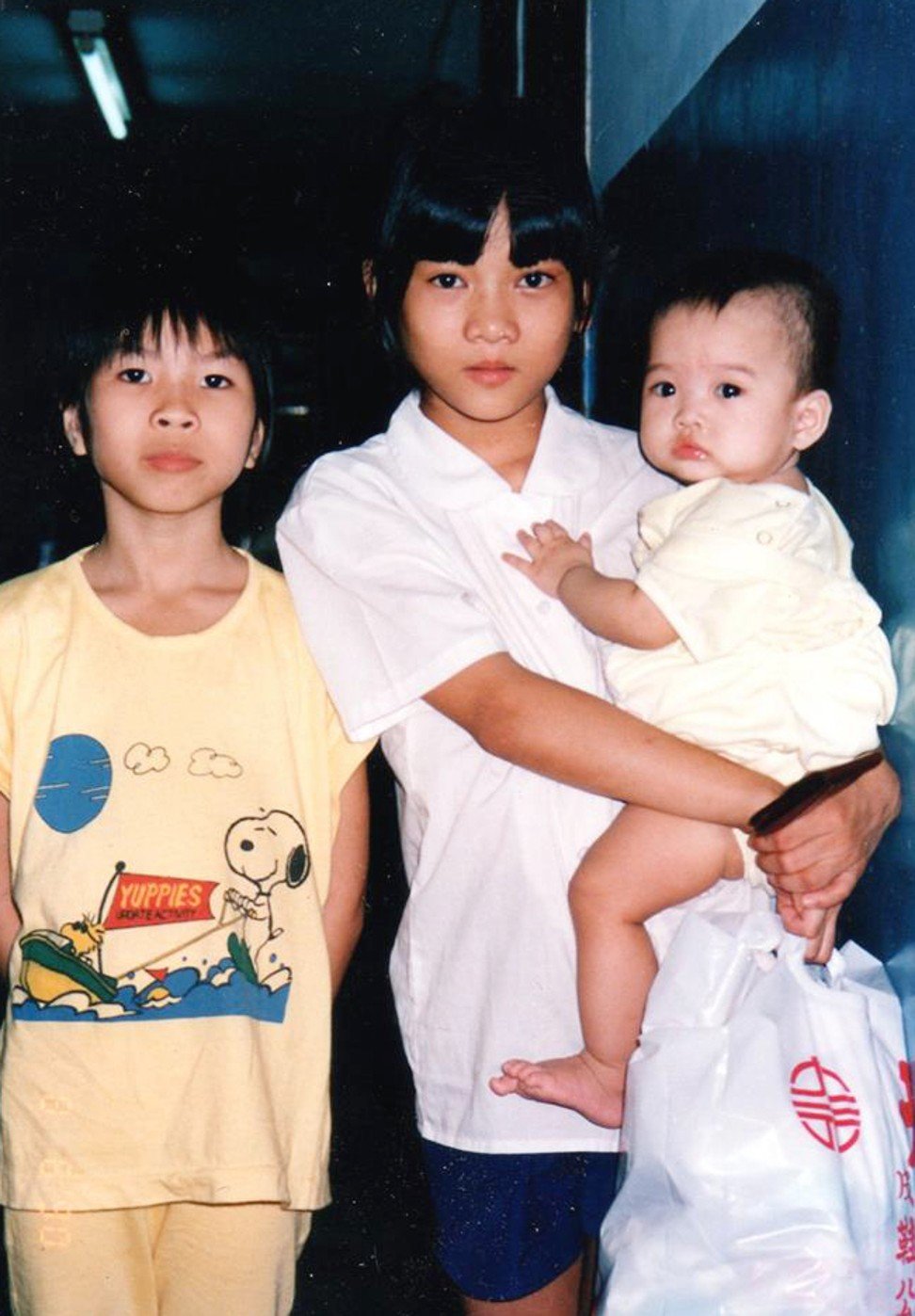

Dang was born in 1981, and spent her childhood in the camp. She remembers the communal lifestyle where people lived in one open area and slept on bunk beds. Each family occupied about 40 sq ft.

“It was just a bed space with a curtain – that was your privacy,” she says, adding how she would accidentally knock over items placed at the end of the bed because of the lack of space.

Due to Hong Kong’s relatively lenient immigration policies at the time, refugees were allowed to work outside the camp. Dang’s father took on several odd jobs as a delivery man and construction worker, while her mother ran a hawker stall inside the camp selling traditional Vietnamese food.

As a child growing up in Hong Kong, her mother’s delicious offerings, mainly banh cuon – a type of rice noodle roll from northern Vietnam – were her main link to her cultural roots.

Outside school, Dang cared for her younger siblings. She is the second-eldest among the children in her family, and the only girl.

While life was hard, it also brought simple joys. “I just needed to open the curtain and my friends would come to play with me,” she says.

“I don’t think children nowadays have that kind of happiness.”

When she left for Britain in 1992 at 11, she recalls shedding tears, not for the harsh conditions but for the friends she was leaving behind.

By 2000, the Vietnamese situation in Hong Kong was largely resolved, according to government records, with 143,700 refugees resettled in other countries and 67,000 repatriated.

Dang’s family lived in a 1,500 sq ft house outside London with a garage and a garden. It was the first time she had her own private room.

But as the only Asian in her class at school, Dang suffered racial discrimination, which brought on an identity crisis. To fit in, she never brought up her refugee days in Hong Kong.

“How do you tell someone that you are a refugee? It was not an easy thing and I didn’t want to be treated differently,” she says.

After graduating from the European College of Business and Management in London under scholarships, she became a chartered accountant and worked in investment banking for 10 years.

But deep down she always felt a call to return to her birthplace.

The opportunity came in 2009 when her husband, an Austrian-German, was offered a position in investment banking in Hong Kong and she encouraged him to take it.

It has been 10 years and the couple now live in Wan Chai with their daughter, seven.

Feeling grateful for the help her family received back then, Dang had an urge to give back to others.

Call it serendipity – but she only found out later that Christian Action also once managed Kai Tak Camp.

Cheung-Ang Siew Mei, executive director of Christian Action says Dang’s experiences and support for refugees are inspirational. “Farah is thankful and she is paying it forward by helping other refugees. It is good for people to remember that refugees are grateful for what has been done for them.”

Having only come to terms with her refugee identity at 30, Dang, now a British citizen and Hong Kong permanent resident, tells others going through what she has experienced to keep faith and be positive.

“I’m happy to tell people I’m a Vietnamese refugee and I’m proud of my roots.”