Opinion | Letter of the Law: The fine line in Hong Kong between freedom of speech and national security

In conflicting legal arguments, advocates of freedom of speech seem to have a stronger case, but don’t discount national security

“I want real universal suffrage.” Is the phrase protected speech under the Basic Law? Does police discouragement of hanging the banner represent an un-Basic-Lawable (as the word unconstitutional clearly doesn’t apply) “restriction of freedom”? Or do hikers putting banners on Lion Rock pose a threat to national security? In short, the answer is both.

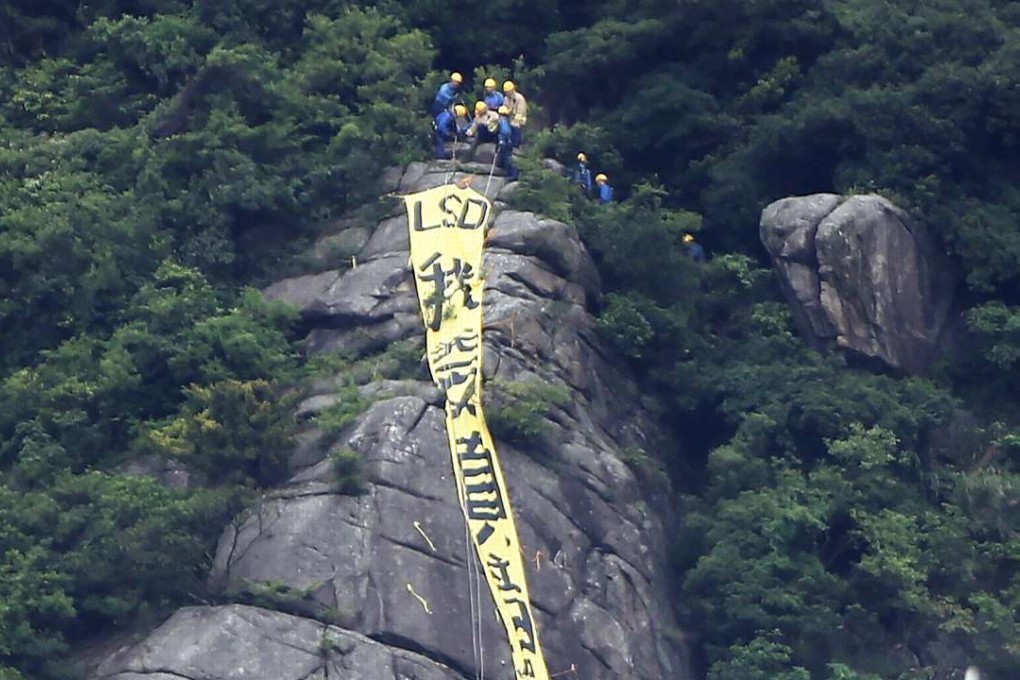

The police camped near Lion Rock in an attempt to dissuade activists from putting up the same banner they put up during the umbrella movement. They failed. The banner went up on nearby Beacon Hill.

According to press accounts, the police claimed to act in the interests of national security. They also probably wanted to protect the nation’s security as well.

What does Hong Kong’s emerging jurisprudence tell us about the legality of both the protesters’ and police’s actions?

Advocates of freedom of speech seem to have a stronger legal case. Article 27 of the Basic Law provides unequivocally for freedom of speech. Nowhere does the article provide for “freedom of speech, except when Zhang Dejiang comes to town.” The banner is clearly speech. If the League of Social Democrats allies who eventually put up the banner had a quasi-religious belief in their views, one might half-jokingly argue that Article 32 applies (protecting freedom of conscience). Yet, we don’t have the right to free speech. Indeed, few countries around the world recognise speech as a natural right.