Why abuse of police in other countries carries harsher consequences than in Hong Kong

From the row over officers jailed for beating up a protester have come calls to criminalise insults against police. Such laws are not without precedent

Insulting police could land you in prison in Singapore, Macau or parts of Europe. But it would probably get you nothing more than a dirty look in Hong Kong. At least for now.

But others have warned the proposed law would exacerbate tensions, and could limit freedom of expression.

Legislator and barrister Dr Priscilla Leung Mei-fun is one of the main proponents of a change. She believes if insulting the police got people fined, it would send a message that the behaviour was unacceptable, and would make it easier for police to do their job.

Hong Kong law criminalises resisting lawful arrest, wilfully obstructing a police officer, acting in a disorderly manner, and physical assault.

But it doesn’t specifically make insulting officers an offence.

Hong Kong police have guidelines for confrontations, and the force said it provides a 24-hour support network for its officers’ stress-related problems.

But in a Facebook post last month, the force said police work was “arduous” and managers were “open to any new measures or legislation that would enhance the effectiveness of policing”.

Pro-establishment lawyer Lawrence Ma Yan-kwok, chairman of the China-Australia Legal Exchange Foundation, which helps Hong Kong and Australian lawyers understand the mainland, backs a change. He said people might not like facing the police, but they should not abuse officers.

“You want to go and protest, go and protest,” he said. “You shouldn’t take out your anger on people who are performing their job.”

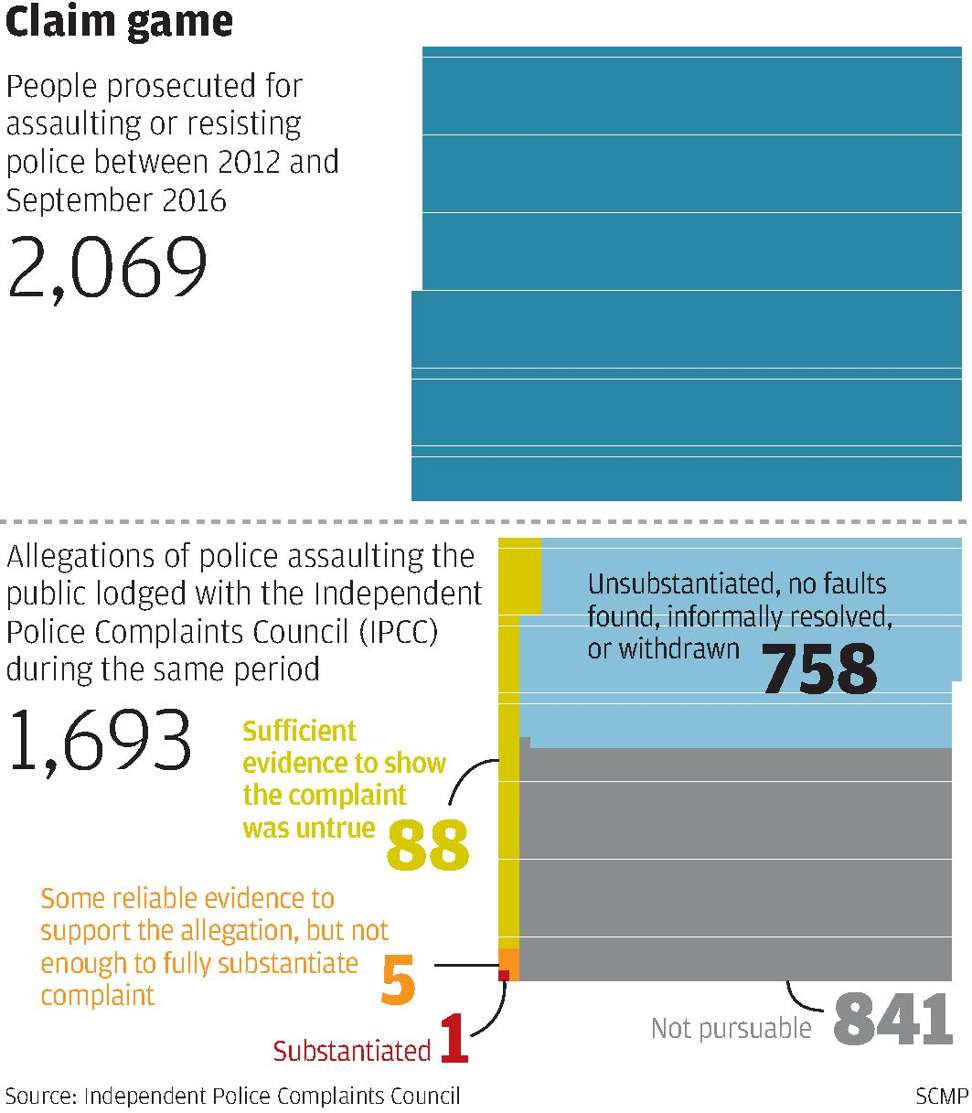

Between 2012 and September last year, 2,069 people were prosecuted for assaulting or resisting police. The force does not maintain statistics on insults.

During the same period, police watchdog the Independent Police Complaints Council (IPCC) got more than 1,693 allegations of police assaulting the public. Only one was deemed “substantiated”.

More than 8,200 complaints have been made since 2011 relating to police misconduct, improper manners or offensive language. Because the IPCC considers allegations of offensive language or impoliteness a minor complaint, these are often informally resolved.

The IPCC claimed there was no evidence to show police were more likely to assault the public if they had been insulted. But a spokesperson said a law change could dissuade people from making complaints against the police, or create conflicts between police and the public.

A ‘necessary’ provision

Other countries have had laws against insulting police for decades. In Singapore, it has been an offence since 1906 to insult a public officer, and lawyers in the city state say it has been uncontroversial. Anyone who threatens, abuses or insults a public servant or public service worker could face a S$5,000 (HK$27,000) fine and up to one year in jail.

National University of Singapore law professor Kumaralingam Amirthalingam said the laws are a necessary deterrent.

“You do need to ensure that police officers and public service workers are protected so that they can ensure public safety,” he said. “They do not choose to be in a situation of confrontation; they have no choice but to go into situations of danger or conflict.”

You need to ensure police officers are protected so that they can ensure public safety

“We are in an era of constant revolution and protests,” he added. “These are vital to functioning democracies. But they are also tinderboxes that can cause considerable collateral damage to innocent citizens.”

It is an uncontroversial law, said Macau-based litigant Francisco Leitao, who as a lawyer has the same legal protections as a police officer.

“The law considers that a person who voluntarily takes this action of insulting a lawyer or insulting a public official because of their duties ... deserves a higher degree of reproach than someone who simply insults a normal person,” he said.

Macau rights activist Jason Chao Teng-hei said he had no problem with the law itself. Instead, he said the context made it unfair. Chao, who warns fellow activists about the law before they protest, said citizens’ lack of universal suffrage and what he sees as a compromised justice system means police enjoy an unequal level of protection.

“Our major concern is the inadequacy of means for the citizens to protect themselves,” he said. He said he thought it was a bad idea to introduce similar laws in Hong Kong, where he said the police force is “out of control”.

He said: “Hong Kong and Macau citizens are denied universal suffrage. There are virtually very few means for us to hold the police officers and those at the top of the power hierarchy accountable.”

A valid restriction?

In France, the penalty for insulting police was doubled last month to a year in prison or a fine of 15,000 euros (HK$124,000). About 17,000 people each year are prosecuted for the offence, according to figures from Amnesty International, whose researcher Marco Perolini said the law has gone too far. He said officers used the offence to arrest protesters on “vague grounds”, and could use it to limit free expression.

Other countries have decided it is more important to protect freedom of expression.

In Australia, for instance, a magistrate in the state of Queensland ruled in 2010 that a man did nothing illegal when he told a female police officer to “f*** off” outside a nightclub.

Hong Kong lawyer Ma acknowledged the law would limit freedom of expression. But it would be a reasonable restriction, he said.

And if the law passed and someone launched a legal challenge as to its constitutionality, he would defend the law in court, he said.

You’ve got to be able to handle a bit of abuse to be a public officer

“We should encourage and assist [the police] in performing their duties because they’re performing their duties for the public good,” he said. “They’re not performing duties to protect their own interest.”

Are you insulted by this?

It is something we learn early in life: what is insulting to one person might not be to another. This, detractors say, is another problem with criminalising insults.

“It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to define what ‘insult’ means. Is it a subjective feeling, or is there an objective measurement as to what ‘insult’ really means?” he said.

“If we really wish to criminalise insulting police officers, we have to be extremely cautious to strike a balance so that freedom of expression will not be infringed.”

But lawyers in Macau and Singapore said there is ample precedent to help courts determine what counts as an insult.

National University of Singapore’s Amirthalingam said what counts as an insult depends on the country or person involved, and insulting words would most likely need to breach the peace.

In Hong Kong, Democratic Party legislator Lam Cheuk-ting said it was unfair to afford more protection to police than to the public. He said the imbalance would only worsen the relationship between police and the public, and that officers could end up handling hundreds of insult cases a day.

Jeffrey Herbert, who worked with the Hong Kong force for 30 years and wrote the Complaints Against Police manual in 1980, said the lesson from Tsang’s assault was that police needed to look into how they supported their frontline officers, in ways other than through legislation.

And he offered some simple advice for officers struggling with insults from the public: “Grow up.”

“You’ve got to be able to handle a bit of abuse to be a public officer,” Herbert said. “Every police force in the world has to deal with riots and much worse. In many ways we should be happy to police Hong Kong.”