Hong Kong’s High Court rules police need a warrant to search mobile phones

The only exception is if circumstances are ‘exigent’, court says, as human rights activists laud the review outcome

The High Court on Friday declared that Hong Kong police must have a warrant to search the digital content of seized personal technology items, unless it is to prevent imminent danger to the public, the possible destruction of evidence or if the discovery of evidence is “extremely urgent”.

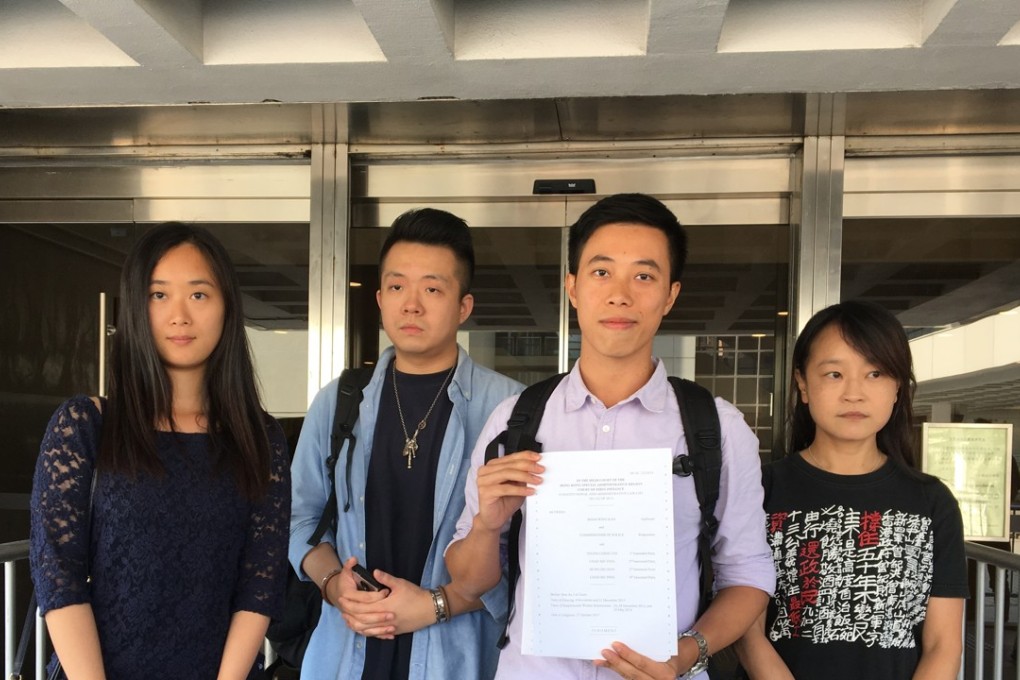

Activists lauded the outcome of the judicial review, saying it was a “remarkable day” for efforts to protect human rights and personal privacy.

Hong Kong’s High Court to rule on whether police can seize mobile phones

The case raised important questions of whether this practice is allowed under the Police Force Ordinance and whether it is constitutional, given that individual privacy is protected by the Hong Kong Bill of Rights and the city’s mini-constitution, the Basic Law.

The court ruled partly in Sham’s favour as Mr Justice Thomas Au Hing-cheung found the ordinance only empowers a search in “exigent circumstances”.

Most times, police have efficient and effective access to obtain a search warrant from a magistrate, he said.

But there may be scenarios where there is a reasonable basis to suspect that a search may prevent an imminent threat to safety of the public or police officers, prevent imminent loss or destruction of evidence, and lead to the discovery of evidence in extremely urgent and vulnerable situations.

“Given the high importance in protecting the massive and extensive personal information and data, and to give meaningful effect to the constitutionally protected right to privacy and freedom of private communication against unlawful intrusion,” Au wrote, “it is only proportionate to achieve the objective of effective law enforcement by permitting warrantless search for the digital content of mobile phones seized on arrest only in exigent circumstances.”