One in four Hong Kong properties has illegal structures, but most owners get away with their misdeeds

Each year, the Buildings Department receives about 29,000 complaints of unauthorised building works but ends up prosecuting only 8 per cent of errant owners

The 2,000 sq foot luxury house in an exclusive estate in Tai Po comes with a garden, but its structural plan – approved by authorities – does not show a 300 sq ft basement, a swimming pool and a second living room.

Yet on some days, the strains of popular ditties and the clicking of tiles can be heard from the underground space, which has been kitted out as a mahjong room and a karaoke lounge

The current owner of the house in Hong Lok Yuen knows the additions – which came with the HK$20 million property (US$2.56 million) – are illegal but maintains that they are justified.

“Who doesn’t want to live in a bigger house?” the owner said, speaking on condition of anonymity.

“With properties so expensive now, it’s much better value for money to make your own house bigger, rather than buying one at three times the cost [of renovations].”

The owner said the entire estate, with 1,150 villas, had similar secret features.

“There’s a saying that people would only buy a house here because they know there are illegal [additions],” the owner said.

A city of illegal structures

Hong Kong, one of the world’s most densely-populated places, is a city of illegal structures.

These run the gamut from supporting frames for air conditioners, canopies, rooftop structures, enclosed balconies and signboards on residential, commercial and industrial properties.

Buildings Department figures from the past 18 years suggest at least one in four properties has unsanctioned features.

Teresa Cheng isn’t the first - other big names caught out over illegal structures

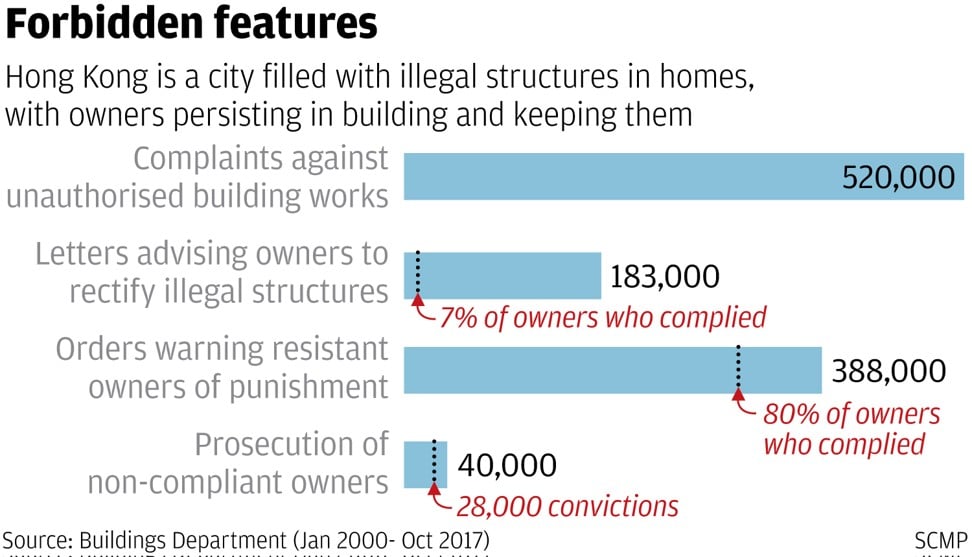

From 2000, the earliest records available, to October last year, it received 520,000 complaints about unauthorised building works in all properties (excluding village homes), or about 29,000 complaints each year.

Public anger over illegal structures flares up every so often, especially when famous, rich or powerful owners are involved.

The latest scandal erupted earlier this month when the department found 10 illegal extensions in adjoining houses belonging to newly-appointed justice minister Teresa Cheng Yeuk-wah and her engineer-husband Otto Poon Lok-to.

Cheng said she had overlooked the structures and had not made any alterations to the three-storey house in Villa de Mer, Tuen Mun, after she bought it in 2008.

But after a copy of her mortgage deed surfaced and showed no mention of any additions, critics alleged a cover-up, questioning how Cheng, a barrister and chartered engineer, could have overlooked the structures.

Cheng’s fate remains to be seen but a similar scandal put an end to former number 2 official Henry Tang Ying-yen’s bid in the 2012 chief executive race, even though he was then the front-runner.

The discovery of an illegal 2,300 sq ft basement – reportedly replete with a wine cellar and a Japanese bath – in his home in Kowloon Tong was believed to be the main reason for his eventual defeat in the election.

Tang’s popularity nosedived after he blamed his wife Lisa Kuo Yu-chin for constructing the basement during the “low ebb” of their marriage, while a teary-eyed Kuo admitted she was guilty.

Up in arms over the issue

“In Hong Kong, a square foot of land is worth more than an ounce of gold,” Civic Party lawmaker Tanya Chan Suk-chong said.

“When common people are finding it so hard to afford a home, they will wonder why some people can gain extra living space for free by building illegal structures …[especially] when high-ranking government officials and even former chief executives are involved in this.”

Hong Kong is the world’s most expensive among 406 cities for homebuyers, according to the Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey.

Since 2003, the city’s private home prices have jumped by 445 per cent with chief executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor pledging that her administration will provide more affordable housing, including looking for new sources of land to build homes.

Home prices soared for a 20th straight month last November, the longest rally since 1993, while latest government statistics showed that around 3 per cent – or 209,700 – of the population were crammed into subdivided flats, which range from 75 sq ft or 140 sq ft.

Then, there is also the issue of safety, Chan added. There have been several fatal incidents –

in August 1994, one person died and eight were injured when an illegal concrete canopy of a seafood restaurant in Aberdeen collapsed as workers dismantled a fish tank on it.

More recently last August, three people died when a fire broke out in an illegally partitioned unit in Mai Sik Industrial Building in Kwai Chung.

Vincent Ho Kui-yip, a former president of the Institute of Surveyors, said these incidents probably fuelled public outrage and led to several government campaigns to remove illegal structures.

Ironically, when Lam was development secretary in the previous administration, she led a crackdown on unauthorised building works after a series of high-profile exposés about six years ago.

But she is now facing criticism for backing Cheng and asking the public for “tolerance” as the beleaguered justice secretary rectifies her properties.

Forcing a teardown

Despite the risks, many owners insist on keeping illegal additions to their properties.

From January 2000 to October last year, the Buildings Department issued some 183,000 advisory letters asking owners to return their properties to their original state, but only 7 per cent complied.

It was not until the department issued statutory orders with warnings of punishment for non-compliance – totalling 388,000 notices – that 80 per cent of owners acted.

Former Democratic Party lawmaker Lee Wing-tat, chairman of think tank Land Watch, said owners were motivated to dig in their feet.

“In Hong Kong, the land and property prices are way too high and every extra 10 to 20 square feet means one more bedroom, so flat owners will naturally try to enclose their balconies or build rooftop sheds when they can,” he said.

By keeping quiet, owners would not have to pay the government for extra square footage.

In Teresa Cheng’s case, the 10 structures in both houses add up to 1,800 sq ft of space and would be worth HK$35 million, based on the value of her husband’s home when he bought it in 2012.

Communicating with the government is difficult. I can’t ask them to come to my house every time I want to make an alteration. At the painfully slow pace they work at, no one would be able to renovate their house

Tedious government procedures to approve alterations and strict regulations from different departments also deter owners from coming clean, according to veteran surveyor Vincent Ho.

The Lands Department would review the conditions of the lease, while the Buildings Department would look at the impact of the proposed alterations on fire safety, ventilation, lighting and building structure. The Town Planning Department would look at height restrictions and neighbourhood planning.

“Only very experienced experts can properly assess whether the proposed alterations will fulfil all the requirements and submit building plans accordingly, and they are not cheap,” Ho said. “You also need to pay the government for processing the applications.”

“At the end of the day, time is money,” the Hong Lok Yuen homeowner said.

“Communicating with the government is difficult. I can’t ask them to come to my house every time I want to make an alteration. At the painfully slow pace they work at, no one would be able to renovate their house.”

There is also minimal prosecution of those who flout the law, with relatively light penalties, Lee pointed out.

Hong Kong property owners beware! Illegal structures risk lives and can lead to heavy penalties

The Buildings Department usually responds to complaints and does not conduct proactive investigations. It only follows up on the case intensively if the illegal structures are found to be a safety risk.

But upon issuing a statutory order, it would also register the order with the city’s Land Registry, which is expected to lower the value of the property.

Prosecution can happen if the owners fail to take action within two months of receiving a statutory order. But these do not happen often, with 40,000 cases taken to court out of 388,000 orders, and only 28,000 convictions.

Lee acknowledged that it would be difficult for the department to prosecute cases more actively as gathering evidence was challenging, given that it needed an owner’s permission to enter their property and inspect it.

The courts might also be overloaded if there were too many cases to prosecute.

Thus, the rich and powerful have in the past utilised different methods of appeal to stall enforcement, he said.

No easy fixes

With better-off Hongkongers able to game the system, it is not surprising that indigenous villagers have fiercely fended off the government’s attempt to come down on them.

Lam in 2012 launched a reporting scheme for illegal structures in New Territories village houses, where owners could keep the additions if they were deemed safe by a qualified person but had to demolish them if they were deemed risky.

But it was violently countered in the New Territories, with rural committees applying for judicial reviews and going to Beijing to make their case to the central government.

Half of all illegal structures in New Territories feared unreported

A year later, over 100 police officers had to protect authorities trying to remove illegal structures in Tai Tong Lychee Valley in Yuen Long.

“For people crammed in downtown areas, they may feel the system is quite unfair,” Lee said. “Why have they become an easy target while the rich and powerful can do what they want?”

Ho believed the government was doing the right thing by focusing on high-risk illegal structures given its limited resources and manpower.

He added that another problem was relocation. Many illegal structures involved subdivided flats and rooftop houses which housed low-income families.

“Where will they go if their shelters are dismantled?” Ho asked.

Ho urged the government to make it easier for building owners to play by the rules. For example, having a consolidated set of clear guidelines on alterations, so that people would know when they needed to submit applications and what information to provide.

Currently, the government allows owners to conduct minor, non-structural alterations without needing permits but even professionals are not always clear about its definition.

“For example, installing a solar-powered water heater is categorised as a minor work, but is installing solar panels on the roof a minor work as well?” Ho asked.

The Buildings Department, he said, could levy a fine on those found to have unauthorised building works on their property, with the penalty accruing interest so that owners would have less incentive to delay making fixes.

Lee pointed out that in the long-term, having more affordable housing would reduce the problem of illegal structures.

But this scenario looked unlikely, he admitted.

“When bread is too expensive, the government can flood the market with flour so the prices will come down. Now can the government flood the market [with land]?

“Will it be willing to flood the market? I don’t think so, because [it would affect developers’ pockets] and in Hong Kong, real estate and politics are always connected.”

Additional reporting by Naomi Ng