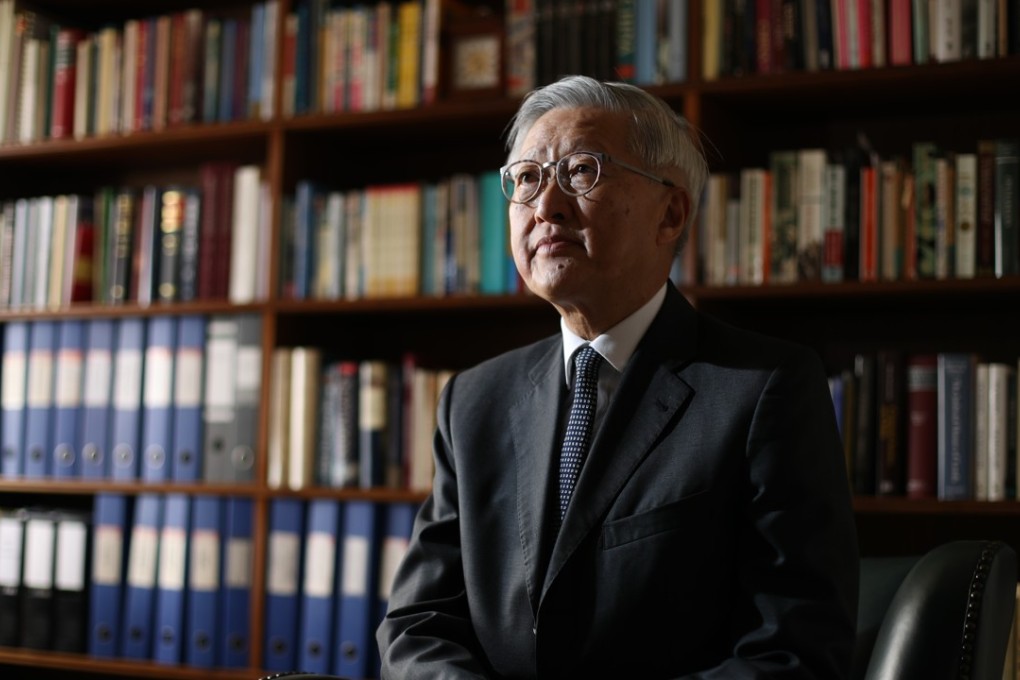

Sticking to his legal principles: former Hong Kong chief justice Andrew Li reflects on how rule of law has fared in last two decades

Today marks the one-month countdown to July 1 , the 20th anniversary of the return of Hong Kong to China. In the start of a weekly series on the handover, we focus on the rule of law in an interview with former chief justice Andrew Li Kwok-nang

Hong Kong’s legal system has been through some tumultuous times in the two decades since 1997. The first post-handover chief justice, Andrew Li Kwok-nang, tackled challenges arising from the new constitutional order, where the city’s common law tradition came up against the mainland regime under “one country, two systems”.

As Li put it, there were bound to be “tensions and grey areas” under the unprecedented governing model: while Hong Kong enjoys a high degree of autonomy and judicial independence, China maintains the final say on how the Basic Law, the city’s mini-constitution, is interpreted. Often, it holds a different view on when and how it should intervene.

Since the handover, the mainland has interpreted the Basic Law five times over matters ranging from immigration and political reform to how lawmakers should swear their oaths. It has also issued a white paper declaring the country had “comprehensive jurisdiction” over Hong Kong and judges must be patriotic.

The legal profession has held silent marches and lamented “the darkest days for the rule of law”. But Li remains optimistic, while sounding a note of vigilance. Here is how he sees the past, present and future.