Why Carrie Lam needs to prove herself before she can lure talent to Hong Kong’s governing team

Pundits say incoming leader must deliver results before she can get talented individuals on board, but the city’s governing system means the odds are stacked against her

The good news is she has managed to assemble her cabinet, which is likely to get Beijing’s approval as early as Wednesday.

The bad news is she has not been able to deliver on a promise for a more diverse slate.

“I’m afraid good governance requires higher standards [than just good policies] – public participation, the rule of law, societal consensus, timely response, accountability ... My view today is that the governing team of the next administration should be injected with some new blood,” she said on January 16 when she confirmed her candidacy for the city’s leadership, hours after her resignation as chief secretary was formally accepted by Beijing.

Fast forward five months and Lam, who is less than two weeks away from being sworn in as Hong Kong’s first woman chief executive, is set to unveil a new cabinet with just one new face from outside the bureaucracy – Democratic Party member and social policy professor Dr Law Chi-kwong, 63.

Former chief executives and commentators had argued in the past that the administration needed talent from the business or academic worlds to inject new ideas, ways of thinking and skills to make the city’s governance more transparent and publicly accountable – or simply, better.

But as elites showed a reluctance to join Lam’s cabinet at a time when the city remains politically divided, academics now believe that the incoming chief will need to do things the other way around. She needs to rely on her “practical” team, as she has described it, to first work on issues such as education and housing, and when it starts producing results, more new blood is likely to be attracted to join them.

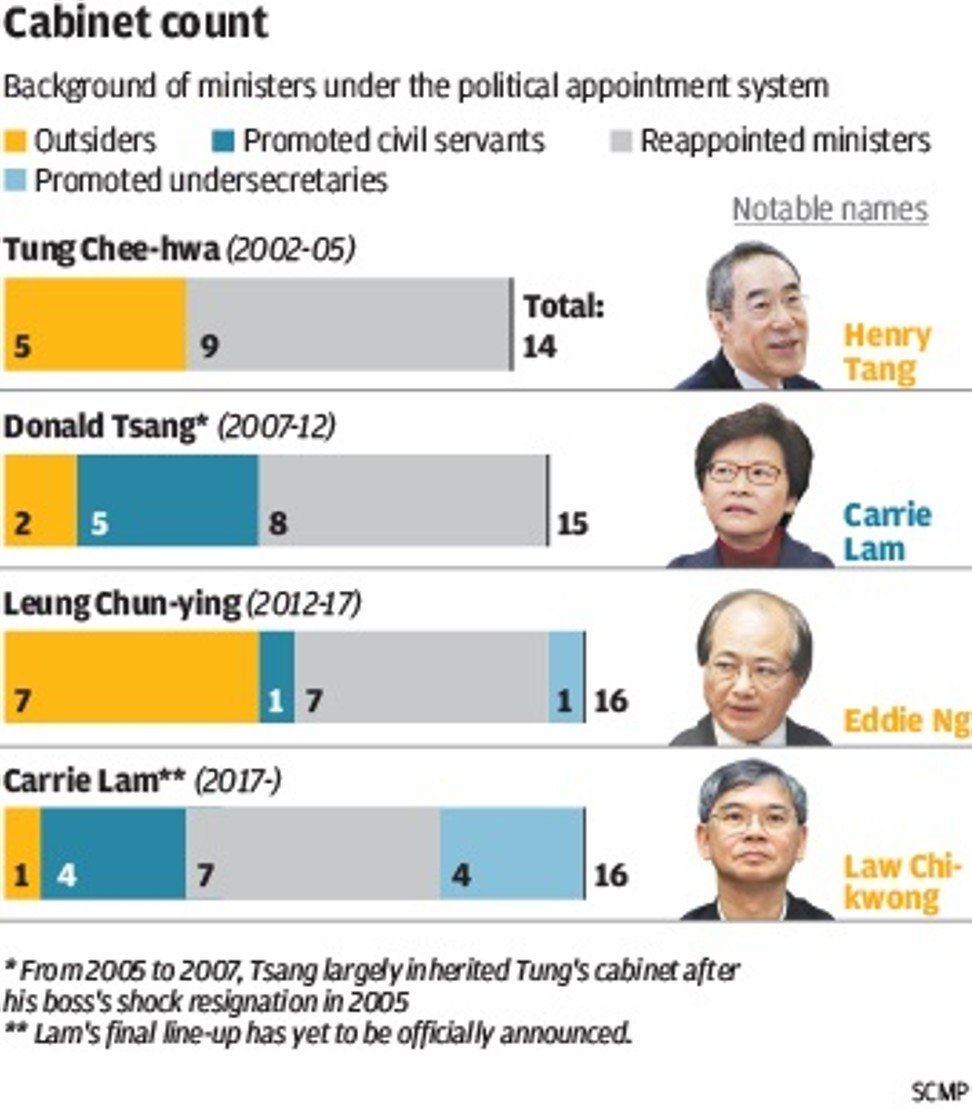

Tung Chee-hwa, Hong Kong’s first post-colonial leader, introduced the ministerial system 15 years ago to improve governance and attract talent from outside the government. Hence, the chief executive found political appointees for policy bureau secretaries and ministers rather than recruit from the ranks of politically neutral career civil servants.

Tung said his Principal Officials Accountability System would mean all principal officials – mostly secretaries of policy bureaus – would be accountable to him for the decisions they made. This arrangement would ensure their sensitivity to policymaking, as their tenure would depend on their ability rather just having the iron-rice bowl mentality of a civil servant.

On June 24, 2002, the businessman-turned-politician declared “the dawning of a new era for the governance” of Hong Kong as he unveiled his 14-strong cabinet with five new ministers from outside the bureaucracy.

But commentators questioned if the team actually produced results as Tung’s popularity continued to drop until he resigned in 2005.

That combination of talent did not yield much success for Tsang either. During his term from 2007 to 2012, a growing feeling set in that the accountability system had failed to work, as various political controversies erupted and led to public calls, in vain, for officials to resign.

Matters became more complicated when Tsang added two more tiers of government leadership in 2008. He introduced his so-called political appointment system, under which undersecretaries and political assistants were appointed at salaries of around HK$200,000 and HK$140,000 a month each.

The new tiers of appointees were tasked to help ministers through lobbying, but commentators argued the three tiers were less capable than the top civil servants in their respective bureaus.

During Leung’s five-year term public perceptions of the system further deteriorated as the former surveyor inducted a record seven outsiders into his 16-strong team.

If her team could make achievements ... it is possible that more people from outside the administration would like to join

According to a University of Hong Kong poll last month, some of those political outsiders, such as education chief Eddie Ng Hak-kim, have remained among the least popular in the cabinet.

Commentators believe that it was the unpopularity of her former colleagues whom Lam worked closely with during five years as Hong Kong’s No 2 official that prompted her to try to introduce young talent and more women into her cabinet.

There was wide speculation that Rex Auyeung Pak-kuen, Asia chairman of a United States-based insurance firm, would become the financial chief, while Teresa Cheng Yeuk-wah, who heads the Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre, was tipped as justice secretary.

However, it was revealed last month that Lam’s final cabinet line-up, that she will likely introduce to the public on Wednesday, would be made up largely of current officials.

Law is expected to become the labour and welfare chief, and the only new face in Lam’s 16-minister cabinet – the lowest influx of fresh faces since the system was introduced in 2002.

City University political scientist Ray Yep Kin-man said Lam’s cabinet line-up showed that the political appointment system had failed to serve its main goals of attracting talent from outside the government and making ministers more accountable.

Yep suggested that after assuming office on July 1, Lam needed to handle political conflict in a more moderate or measured manner and appoint a greater diversity of people to advisory bodies.

This twin focus would improve ties between the executive branch and the legislature, and make the city’s ministerial posts more attractive to executives in the business and professional sectors, he said.

In recent years, Leung has been accused of being too combative in the face of dissenting voices.

Lau Siu-kai, vice-chairman of the Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macau Studies, a semi-official think tank, also believed Lam’s team would need to “get things done” in order to attract new blood and further improve the city’s governance.

“If her team could make achievements, it would strengthen the government’s authority and ... it is possible that more people from outside the administration would like to join,” Lau told the Post.

He believed that the difficulties faced by Lam showed the need for Beijing to urge Hong Kong’s pro-establishment camp to be more united in “building a political coalition”. Members of such a coalition should be willing to take up ministerial posts, he suggested.

However, Horace Cheung Kwok-kwan, vice-chairman of the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong, the city’s largest pro-Beijing force, told the Post it was impractical to expect pro-establishment parties to be eager to take up ministerial posts.

“A party’s lifeline is really to groom talent to win seats in the legislative and district councils,” Cheung said.

Currently, 117 district councillors and 12 lawmakers were DAB members, along with two ministers – Lau Kong-wah (home affairs) and Greg So Kam-leung (commerce).

Former Democratic Party chairwoman Emily Lau Wai-hing disagreed with Cheung’s assessment.

“A party’s goal is to rule with its own cabinet, not to recommend a few people to someone else’s team.

But Hong Kong’s broken system doesn’t allow a party to rule, and it doesn’t make sense,” she said.

It really boils down to the issue of loyalty in Beijing’s eyes

Hui also questioned if Beijing would allow any former democrat to take up more sensitive jobs, such as secretary for security.

“It really boils down to the issue of loyalty in Beijing’s eyes,” Yep told the Post.

But instead of continuing to appoint political assistants who might not be knowledgeable in their respective policy areas, Tsang proposed in March that assistants be replaced with “special advisers” or policy experts.

This area has been a recruiting ground for future leaders in the West. For instance, before becoming a member of Parliament, David Cameron was a special adviser to Britain’s chancellor of the exchequer, or finance chief, and the home secretary in the early 1990s.

In Hong Kong, Ronald Chan Ngok-pang was the only political assistant to be promoted undersecretary since the posts were introduced in 2008. He quit earlier this month to study in the US.

However, Chinese University political scientist Ivan Choy Chi-keung said that without a healthy development of party politics, the chief executive would always be hamstrung by the lack of a political machinery to help him or her lead the government.

Under Hong Kong law the chief executive cannot be a member of a political party. Last year even Tung lamented that the past three administrations – including his own – had failed to run an executive-led government as envisioned in the Basic Law because the leader did not head a party, while lawmakers were popularly elected.

Beijing is widely believed to have taken a negative attitude towards party politics in Hong Kong, but Choy said: “If the structural problem is not tackled ... it will be difficult for the chief executive to establish a strong team spirit in the cabinet, and ministers will continue to fight their own battles and not as a team.”