Huge Indian Ocean quakes in April triggered massive aftershocks

Massive Indian Ocean tremors, part of tectonic plate break-up, triggered large aftershocks thousands of kilometres away

Planet earth may be 4.5 billion years old, but that does not mean she cannot serve up a shattering surprise now and again.

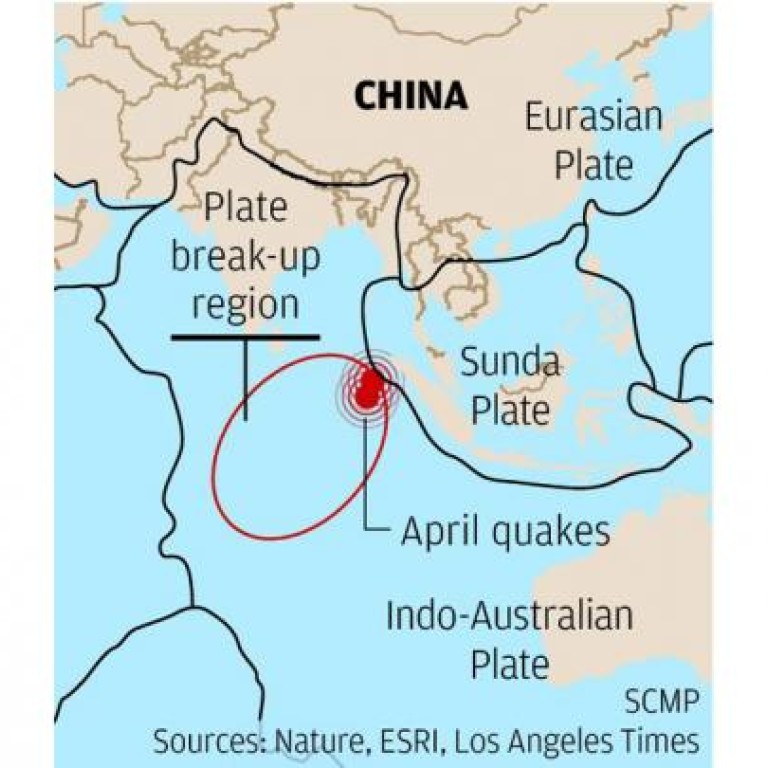

Such was the case on April 11 of this year when two massive earthquakes erupted beneath the Indian Ocean, far from the usual danger zones. Now scientists say the seafloor ruptures are part of a long suspected, yet never before observed, event: the splitting of a vast tectonic plate.

The first of the quakes, a magnitude 8.7, was 20 times more powerful than California's long anticipated "big one" and tore a complex network of faults deep in the ocean floor. The violence also triggered unusually large aftershocks thousands of kilometres away, including four off North America's western coast.

"It was jaw-dropping," said Dr Thorne Lay, a professor of earth and planetary sciences at the University of California, Santa Cruz. "It was like nothing we'd ever seen."

At first, Lay wondered whether the computer code he used to analyse earthquakes was wrong. Eventually, he and other scientists realised that they were documenting the break-up of the Indo-Australian plate into two pieces, an epic process that began roughly 50 million years ago and will continue for tens of millions more.

The scientists reported its findings on Wednesday in the journal .

Most great earthquakes occur along plate borders, where one plate dives beneath the adjoining plate and sinks deep into earth's mantle, a process called subduction. The April 11 quakes, however, occurred in the middle of the plate and involved a number strike-slip faults, meaning the ground on one side of the fault moves horizontally past ground on the other side.

Scientists say the 8.7 main shock broke four faults. The quake lasted two minutes and 40 seconds - most last just seconds - and was followed by a second 8.2 main shock two hours later.

Unlike the magnitude 9.1 tremor that struck in the same region on December 26, 2004, and created a deadly tsunami, the April 11 quake did not cause similar destruction. That is because horizontally moving strike-slip faults do not induce the massive, vertical displacement of water that thrust faults do.

The type of interplate faults involved in the Sumatran quakes are the result of monumental forces, some of which drove the continent of India into Asia millions of years ago and lifted the Himalayan Mountains.

As the Indo-Australian plate continues to slide northwest, the western portion of the plate, where India is, has been grinding against and underneath Asia. But the eastern portion of the plate, which contains Australia, keeps on moving without the same obstruction. That difference creates squeezing pressure in the area where the quakes occurred.

The study authors say that over time, as more quakes occur and new ruptures appear, the cracks will eventually coalesce into a single fissure.

"This is part of the messy business of breaking up a plate," said University of Utah seismologist Dr Keith Koper, senior author of one of the studies. "Most likely it will take thousands of similar large quakes for that to happen."

The quake was also notable for triggering powerful aftershocks far away. While major quakes have been known to trigger aftershocks at great distance, they are usually less than 5.5 in magnitude.

The April earthquake triggered 11 aftershocks that measured 5.5 or greater in the six days that followed the main shock, including one as big as magnitude 7. Remote shocks were felt 10,000 to 20,000 kilometres from the main quake, halfway around the globe.