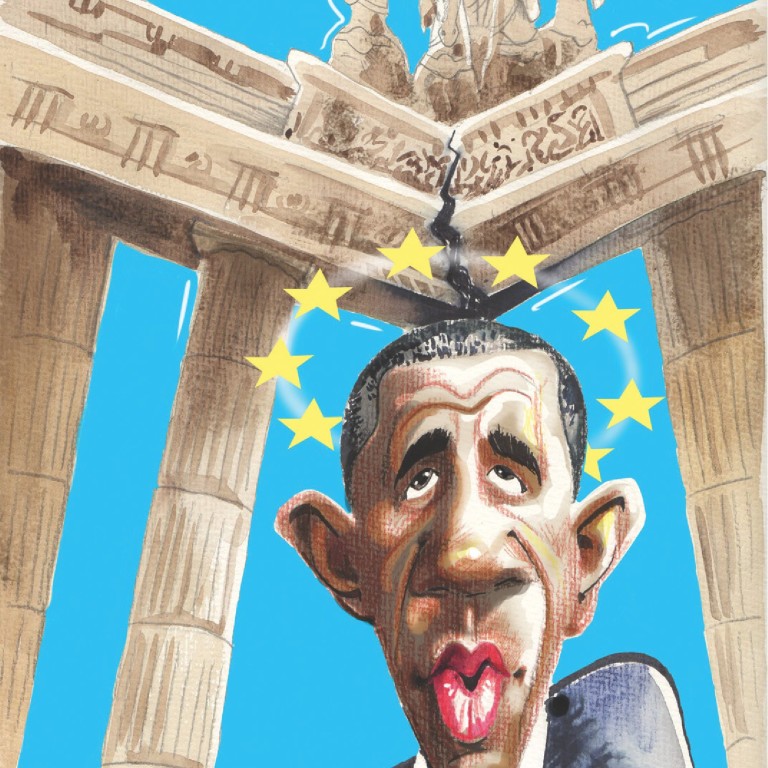

European mission shows honeymoon is over for Obama

Humiliation after call for cut in nuclear arms at Brandenburg Gate and German scepticism on surveillance scandal show honeymoon is over

Barack Obama went to Europe with his expectations set low. He met them.

He and other western leaders were unable to move Russian President Vladimir Putin to take a stronger stand on Syria.

At the Group of Eight industrial nations summit in Northern Ireland, he faced a grilling from US allies about National Security Agency surveillance of international internet data.

The centerpiece of Obama's three-day trip was supposed to have been his address at the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin.

But his headline-making call for a reduction in nuclear weapons was rejected by the Russians within hours.

Officials said 4,500 people were present at Obama's Berlin speech, far fewer than the 6,000 tickets distributed.

At their news conference, German chancellor Angela Merkel responded to Obama's assurances over the surveillance scandal with distinct scepticism.

"The unanswered questions - and there are a few - we will continue to discuss," she said.

All in all, it has been an embarrassingly underwhelming week for the US president.

The contrast between the rhapsodic reception he received in Berlin in 2008 when he was first campaigning for the presidency could not have been more clear. Then, 200,000 Germans packed a park to hear Obama speak.

Michael Hirsh wrote in the , a magazine aimed at Washington insiders, that the honeymoon between Obama and Europe is long over and the marriage itself is becoming deeply troubled.

Nowhere has Obama been as popular as he was in Europe, a collection of traditional US allies viewed by the George W. Bush administration as more of a hindrance than a help amid the security challenges of the post-September 11, 2001, world.

But a Gallup poll published in March showed that the public approval of the US leadership in Europe has dropped 11 percentage points since Obama's first year in office, to 36 per cent.

Even then, it is still far higher than it was during the Bush administration's final year.

"In Europe, especially, Obama was welcomed with open arms, and some people had unrealistic expectations about him," said Nicholas Burns, a longtime senior US diplomat.

He noted that Obama continued some unpopular Bush-era policies, such as the use of drones, and added: "People don't appreciate that American interests continue from administration to administration."

Obama differs from his most recent predecessors, who made personal relationships with leaders the cornerstone of their foreign policies.

The first George Bush moved gracefully in foreign capitals, while Bill Clinton and George W. Bush related to fellow leaders as politicians, trying to understand their own domestic pressures.

"That's not President Obama's style," said James Steinberg, Clinton's deputy national security adviser and Obama's deputy secretary of state.

Such relationships matter, Steinberg said, but they are not the driving force behind a leader's decision-making.

"They do what they believe is in the interests of their country and they're not going to do it differently just because they have a good relationship with another leader," he said.

Sometimes, Obama's recent efforts to forge a rapport with his counterparts have come off as downright excruciating.

Witness, his tough meeting with Putin before the G8 summit. At their joint press conference, Obama tried to lighten the mood by joking about how age was depleting their athletic skills.

"And finally, we compared notes on President Putin's expertise in judo and my declining skills in basketball," he said.

"And we both agreed that as you get older it takes more time to recover," he said.

Putin was having none of it. He waited for the audience to finish laughing, smiled icily and stuck in his spear.

"The president wants to put me at ease with his statement about how he is growing weaker," retorted Putin.

Obama arrived in office determined to invest in Russia's then-president Dimitry Medvedev, but he underestimated Putin's continuing power.

"Obama doesn't really take kindly to being harangued so we knew from the beginning that he and Putin weren't going to have a good basis together," said Fiona Hill, a former top US analyst about Russia and co-author of a book on Putin.

Earlier this month, Obama faced a similarly chilly response from President Xi Jinping when they met in California.

Obama had delivered a stern lecture to Xi about China's disputes with its neighbours. If it is going to be a rising power, he scolded, it needs to behave like one. The next morning, Xi punched back, accusing the US of the same computer hacking tactics it attributed to China. It was, Obama acknowledged, "a very blunt conversation".

While tangling with the leaders of two Cold War antagonists of the US is nothing new, the two bruising encounters in such a short span underscored a hard reality for Obama as he heads deeper into a second term that may come to be dominated by foreign policy: His main counterparts on the world stage are not his friends, and they make little attempt to cloak their disagreements in diplomatic niceties.

His woes in Europe obscured the progress Obama was able to make on economic issues, including moving forward on a free trade agreement with the European Union and commitments to stamp out bank secrecy and deter tax avoidance.

But even those gains came with a price. Obama had wanted the free trade talks to proceed without conditions. But France won a concession when the European Union chiefs agreed to exclude European film, radio and TV industries from the negotiations. It was a sign of the difficulties that lay ahead.

French President Francois Hollande was initially thrilled with Obama because he saw him as an ally against Merkel on economic issues.

But by the time they met at the G-8 on Tuesday, the relationship had soured, according to French analysts, because France is frustrated that the US did not do more to help with the war in Mali and resisted a more robust response to Syria.

British finance minister George Osborne, meanwhile, was none too happy at the G8 summit after Obama said three times that he agreed fully with "Jeffrey" on Britain's plans to crack down on tax avoidance, leaving Osborne red-faced.

Realising his blunder afterwards, Obama joked that he had mistaken Britain's chancellor for the US singer Jeffrey Osborne.

"I'm sorry, man. I must have confused you with my favourite R&B singer," he said, weakly.

British newspaper quoted an onlooker as saying: "Osborne looked put out. It got really cringe-worthy by the end."