Failure of Egypt’s Arab Spring spells dilemma for Obama

Obama struggles to strike balance between fury over oppression of protesters and keeping ties with the military to preserve regional stability

In February 2011, when Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak bowed to a popular uprising and relinquished power, US President Barack Obama welcomed the change and declared: "Egypt will never be the same."

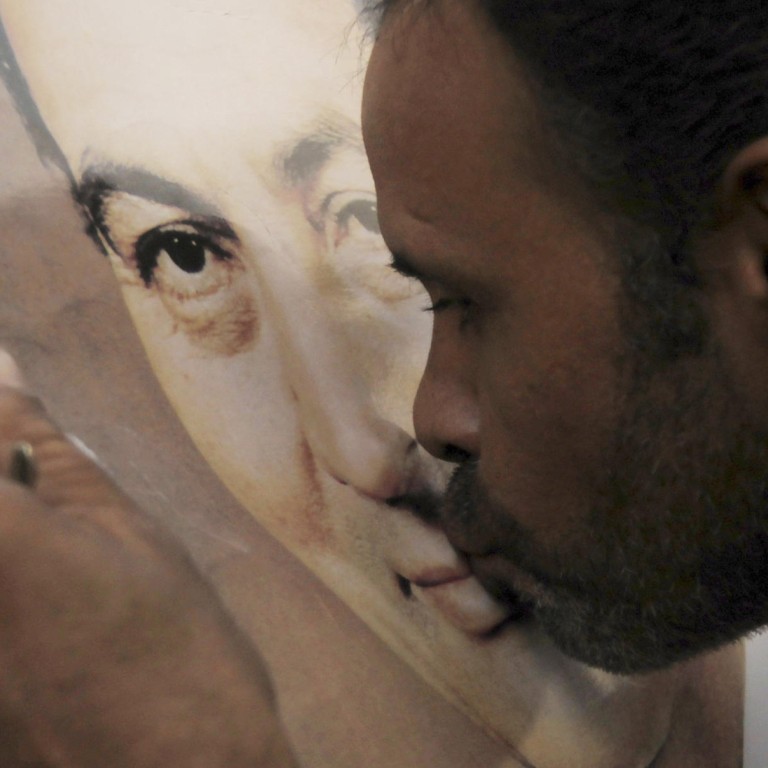

Two-and-a-half years after the elation of the Arab spring, Egypt looks much as it did under the ageing autocrat, only more violently polarised. Critics say Obama has mostly watched from the sidelines.

Mubarak's court-ordered release from prison on Thursday in effect capped the end of Egypt's brief experiment with democracy and its return to military rule.

Over the last two months, security forces have ousted and jailed the first freely elected president, killed or imprisoned hundreds of his Muslim Brotherhood supporters and reasserted the pillars of Mubarak's reviled security state.

Obama's failure to ease the crisis reflects America's diminished ability to influence political outcomes in the Arab world's most populous nation.

Administration officials have struggled to strike a balance. They expressed outrage over security forces shooting civilian protesters, but were careful not to jeopardise ties to the military, which the White House views as key to regional stability, particularly peace with Israel.

The result is a US message that is "tough to explain, and very contradictory, but it is in fact functional", said Aaron Miller, who was an official at the State Department.

"It reflects Obama's very realistic, limited view of America's influence in the Arab spring across the board."

In Egypt, Obama's reluctance to withhold US$1.3 billion in annual military aid stems partly from doubt about whether the military-backed interim government will allow elections once the crisis subsides, as it has signalled, or will cling to power.

White House spokesman Josh Earnest said the aid package was "the subject of ongoing conversation" but remained intact.

Obama's other actions on Egypt have been symbolic. He cancelled a mostly ceremonial joint military exercise that was scheduled for next month and delayed, but did not cancel, delivery of four F-16 fighter jets.

The caution of US officials "reflects not only their sense that they have limited influence over the near-term decision-making of the Egyptian government, but also that they are still trying to discern what the trajectory will be in Egypt," said Tamara Cofman Wittes, director of the Saban Centre for Middle East Policy in Washington.

The risk of a backlash is clear for US policymakers. Egypt could prohibit US warplanes headed to Afghanistan or other hot spots from passing through its airspace, or slow American warships transiting the Suez Canal.

It could also derail US efforts to have Egypt improve surveillance on its borders with Libya and Israel to stop arms smugglers and terrorists, changes that General Abdel Fatah el-Sissi, the army chief, has pledged to make.

"There are plenty of costs to cutting off this aid, and it comes just at the time when, after 30-some years, General el-Sissi comes in and opens up discussions on these issues," said Robert Springborg, of the US Naval Postgraduate School.

"From the American military perspective, this would be a tragedy."

For a few weeks, US-backed diplomatic efforts appeared to help hold off large-scale bloodshed. Defence Secretary Chuck Hagel called Sissi more than a dozen times and senators John McCain and Lindsey Graham met the general in Cairo to urge him to negotiate with the Muslim Brotherhood.

Those efforts fell apart on August 7 and a week later Egyptian soldiers stormed the Brotherhood's protest camps.

Eric Trager, of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, said: "The prospect for getting negotiations between the military and the Brotherhood was always very low and the administration wasted some of its influence by even attempting to get those negotiations going."