Researchers locate the DNA that gives human beings our appearance

Ground-breaking work reprogramming the genome of mice has given researchers a far better understanding of how appearance comes about

Researchers have started to realise how DNA fine-tunes faces. In experiments on mice, they have identified thousands of regions in the genome that act like dimmer switches for the many genes that code for facial features, such as the shape of the skull or size of the nose.

Specific mutations in genes are already known to cause conditions such as cleft lips or palates. But in the latest study, a team of researchers led by Axel Visel of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in Berkeley, California, wanted to find out how variations seen across the normal range of faces were controlled.

Although each face is unique, the actual differences are relatively subtle. What distinguishes us is the exact size and position of things such as the nose, forehead or lips. Scientists know that our DNA contains instructions on how to build our faces, but until now they have not known exactly how it was accomplished.

Visel's team was particularly interested in the portion of the genome that does not encode for proteins, until recently nicknamed "junk" DNA, but which comprises about 98 per cent of our genomes. In experiments using embryonic tissue from mice, where the structures that make up the face are in active development, Visel's team identified more than 4,300 regions of the genome that regulate the behaviour of the specific genes that code for facial features.

The results of the analysis were published on Thursday in the magazine .

These "transcriptional enhancers" tweak the function of hundreds of genes involved in building a face. Some of them switch genes on or off in different parts of the face, others work together to create, for example, the different proportions of a skull, the length of the nose or how much bone there is around the eyes.

"If you think about face development, a gene that is important for both development of the nose and the mouth might have two different enhancers and one of them activates the gene in the nose and the other just in the mouth," Visel said.

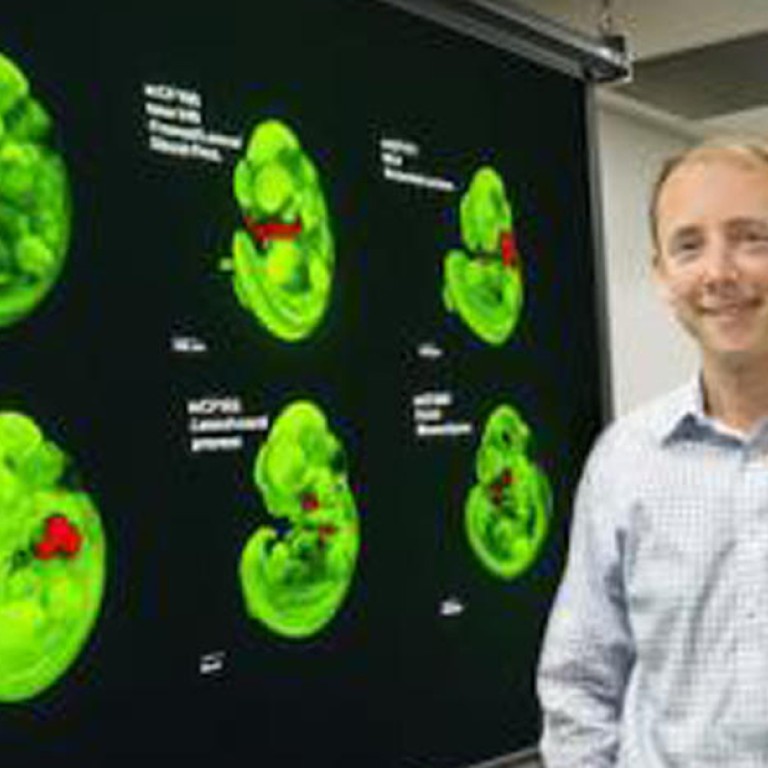

In further experiments to test their findings, the scientists genetically engineered mice to lack three of the enhancers they had identified.

Compared with normal mice, the skulls of the modified mice had microscopic, but consistent, changes.

Importantly, all of the modified mice showed only subtle changes in their faces, and there were no harmful results such as cleft lips or palates.

Though the work was done in mice, Visel said that the lessons applied to humans well.

He said that the primary use of this information, beyond basic genetic knowledge, would be as part of a diagnostic tool for clinicians to advise parents if they were likely to pass on particular mutations to their children.