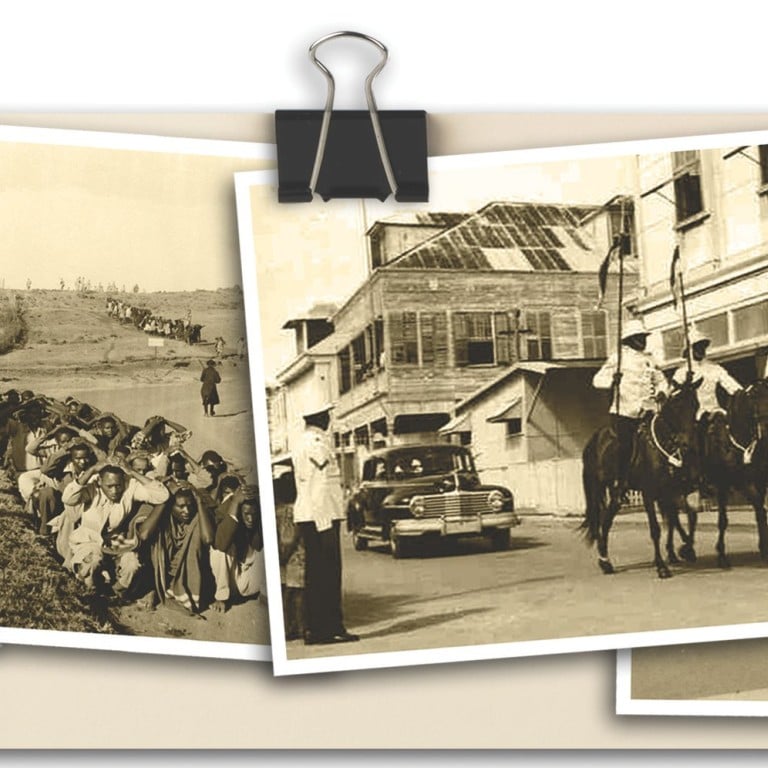

British empire staff burned sensitive files before new nations' birth

Retreating colonial officials went to great lengths to stop new nations seeing sensitive documents

The full extent of the destruction of Britain's colonial government records during the retreat from empire was disclosed yesterday with the declassification of a small part of the Foreign Office's vast secret archive.

Fifty-year-old documents that have been transferred to the UK National Archive show that bonfires were built behind diplomatic missions across the globe as the purge - codenamed Operation Legacy - accompanied the handover of each colony.

[Destroy] all papers likely to be interpreted as indicating racial prejudice

The declassified documents include copies of an instruction issued in 1961 by colonial secretary Iain Macleod that postindependence governments should not be handed any material that "might embarrass [the] government ... police, military forces, public servants or others eg police informers", that might betray intelligence sources, or that might "be used unethically by ministers in the successor government".

In Northern Rhodesia, officials were also given orders to destroy "all papers which are likely to be interpreted, either reasonably or by malice, as indicating racial prejudice or religious bias".

Evidence of the purge had to be erased. Documents "should be reduced to ash and the ashes broken up", while any dumped at sea must be "packed in weighted crates and dumped in very deep and current-free water". Also among the documents declassified yesterday are "destruction certificates" sent to London by officials as proof they were performing their duties, and memoranda that showed some were struggling to complete their huge task.

A confusing classification system was introduced, in addition to secret/top secret, to protect papers that were to be destroyed or shipped to the UK. Officials were often refused security clearance on the grounds of ethnicity. Documents marked "Guard", for example, could be disclosed to non-British officials from the "Old Commonwealth"- Australia, New Zealand, South Africa or Canada.

Those classified as "Watch" were to be removed or destroyed. Steps were taken to ensure post-colonial governments would not learn that such files had ever existed. "DG", said to be an abbreviation of deputy governor, was a code word to indicate that papers were for "British officers of European descent only".

As colonies passed into a transitional phase before full independence, with British civil servants working for local ministers, a parallel series of "Personal" files could be seen only by governors and their British aides, a system that appears to have been employed in every territory from which the UK withdrew after 1961.

While thousands of files were returned to London during decolonisation, it is now clear that countless documents were destroyed. "Emphasis is placed upon destruction," officials in Kenya were told.

Officials in Aden were told to start burning in 1966 - 12 months before British withdrawal. As in many colonies, a three-man committee decided what would be removed to London. The paucity of Aden documentation may suggest that the committee decided that most files should be destroyed.

In Belize, officials told London in 1962 that an MI5 officer had decided that all sensitive files should be destroyed: "In this he was assisted by the Royal Navy and several gallons of petrol."

In British Guiana, a shortage of "British officers of European descent" resulted in the "hot and heavy" task falling to two secretaries, using a fire in an oil drum in the grounds of Government House. Eventually the army agreed to lend a hand.

Not all sensitive documents were destroyed. Large amounts were transferred to Foreign Office archives. Colonial officials were told that crates sent back to the UK by sea could be entrusted only to "a British ship's master on a British ship".

The files show that destroying papers pre-dated Macleod's 1961 instructions. A British official in Malaya reported that in 1957 "five lorry loads of papers ... were driven to the naval base at Singapore, and destroyed ... discreetly".

A few years later, officials in Kenya were told not to follow this example: "It is better for too much, rather than too little, to be sent home - the wholesale destruction, as in Malaya, should not be repeated."

The documents made available yesterday at the National Archives at Kew in London are from a cache of 8,800 colonial-era files that the Foreign Office held for decades, in breach of the 30-year rule set down in the Public Records Act.