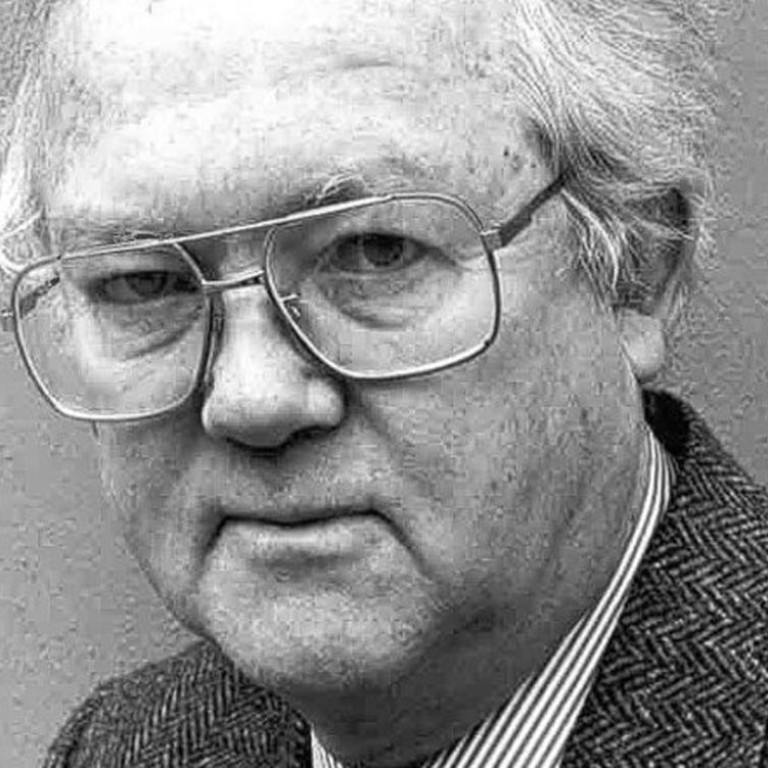

US authority on Chinese art James Cahill dies at the age of 87

James Cahill, an art historian who played a key role in expanding the study and teaching of Chinese painting in the West before and after the opening up of US-China relations in the early 1970s, has died at his home in Berkeley, California. He was 87.

James Cahill, an art historian who played a key role in expanding the study and teaching of Chinese painting in the West before and after the opening up of US-China relations in the early 1970s, has died at his home in Berkeley, California. He was 87.

The cause of death on February 14 was complications of prostate cancer, his daughter, Sarah Cahill, said.

A long-time professor at the University of California, Berkeley, Cahill was a dominant scholar in his field for 50 years. In the late 1950s, he was one of a small number of Western scholars permitted access to the imperial paintings that had been evacuated to Taiwan before the mainland fell under communist rule.

He was allowed to photograph many of the works for , his 1960 text that for decades was required reading in Chinese art history classes.

He helped organise an exhibition of Chinese imperial art from Taiwan's National Palace Museum that opened in 1961 at the National Gallery in Washington. Called "Chinese Art Treasures", the show travelled to other US cities, drawing large crowds to view works unseen by the West since the 1930s.

He also directed a project to produce high-quality colour photographs of thousands of paintings from the National Palace Museum. These became an invaluable resource for other scholars and museums.

"He was a pioneer specialist in the field and had tremendous impact," said Rick Vinograd, Professor of Asian Art at Stanford University who studied under Cahill. "Early in his career, he was really a central figure in bringing knowledge of important monuments of Chinese painting to the general public and the academic world."

In 1973, Cahill was among the first group of American art historians to visit China after president Richard Nixon's historic meeting with Mao Zedong in Beijing the previous year. They were granted extraordinary access to view and photograph rare paintings at the Palace Museum in Beijing.

Cahill, a brilliant lecturer, often took controversial stands.

After the National Gallery exhibit, he argued at a symposium of Chinese art experts that notable Chinese painters during the Ming dynasty were influenced by Western art. This theory was denounced by some Chinese scholars but the notion of foreign influences in Chinese art of that period is widely accepted today.

In 1999, he caused a stir when he claimed that , a reputed 10th-century masterpiece from the Southern Tang dynasty donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, was a fake. He said the painting, attributed to the Chinese master Dong Yuan, was actually painted by well-known forger Chang Dai-chien, who died in 1983. The controversy was widely covered in art and mainstream publications.

The museum stood behind the painting, which remains in its collection, but Cahill never backed away from his judgment and the painting's authenticity is still a matter of debate.