3D printing will change how wars are fought, foreign policy conducted, experts say

Evolving technology expected to reshape way wars are fought, foreign policy conducted and where and how products are made, experts say

3D printing will revolutionise war and foreign policy, say experts, not only by making possible incredible new designs but by turning the defence industry - and possibly the entire global economy - on its head.

For many, 3D printing still looks like a gimmick, used for printing plastic figurines and not much else. But with key patents running out this year, new printers that use metal, wood and fabric are set to become much more widely available - putting the engineering world on the cusp of major historical change.

The billion-dollar defence industry is at the front edge of this innovation, with the US military already investing heavily in efforts to print uniforms, synthetic skin to treat battle wounds, and even food, said Alex Chausovsky, an analyst at IHS Technology.

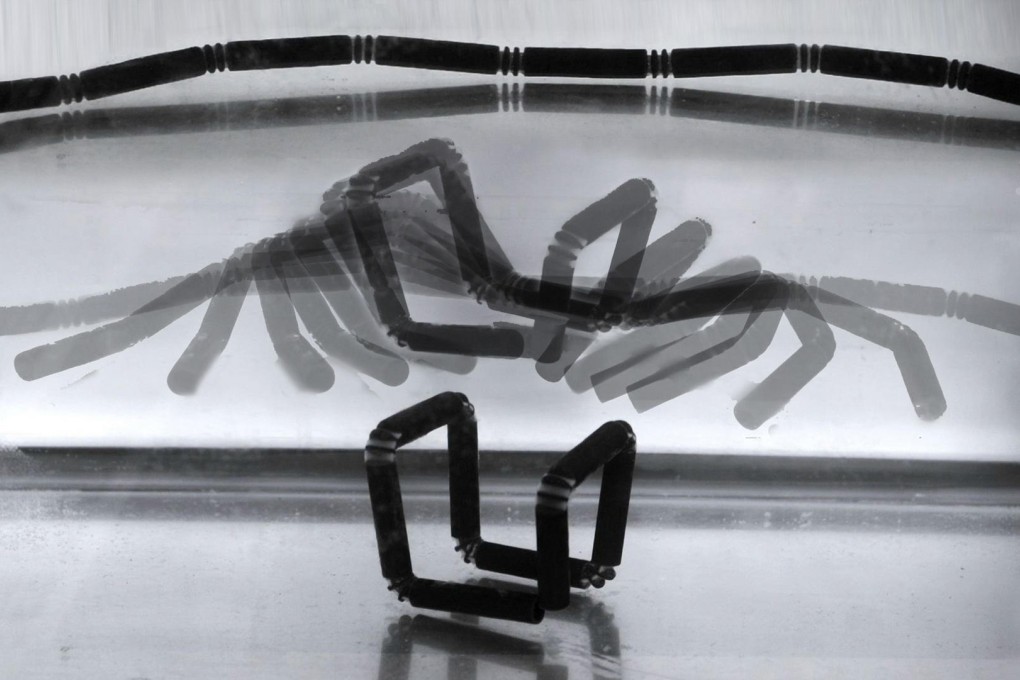

Scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have already invented "4D printing" - creating materials that change when they come into contact with elements such as water.

One day, that could mean things such as printed uniforms that change colour depending on their environment.

In the real world, the baby steps are already being taken. Late last year, British defence firm BAE Systems put the first printed metal part in a Tornado jet fighter. The company recently put out an animated video showing where they think such humble beginnings could one day lead the world to. It imagined a plane printing another plane inside itself and then launching it from its undercarriage.

"It's long term, but it's certainly our end goal to manufacture an aerial vehicle in its entirety using 3D printing technology," said Matt Stevens, who heads BAE's 3D printing division.