Give millions, get grief: For rich philanthropists, a thick skin is a must

To give is to gain a heap of grief if you're a mega-rich donor these days.

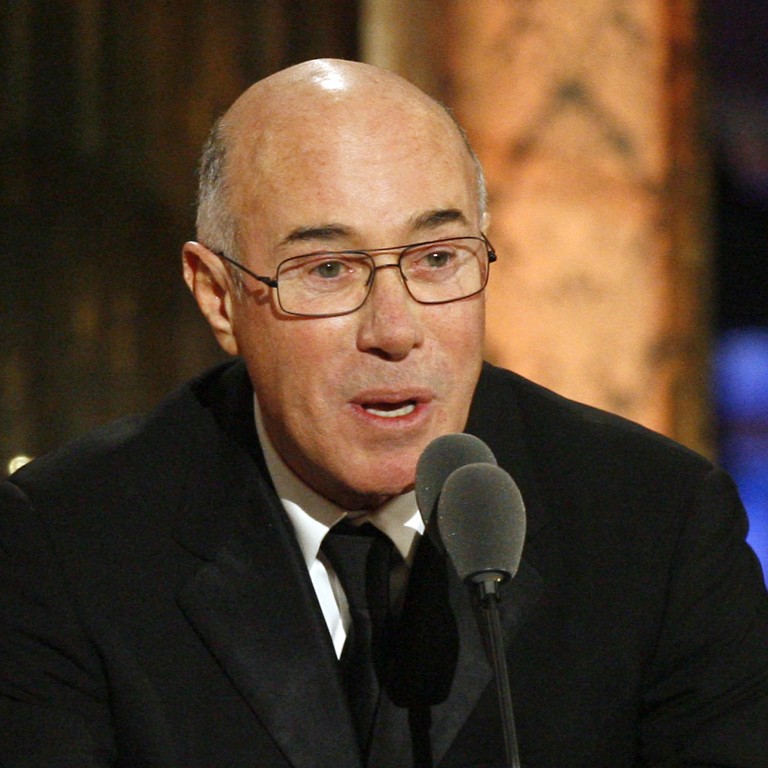

In recent months, a hedge fund billionaire was denounced for his US$400 million gift to the already wealthy Harvard University, David Geffen took flak for gifts that plaster his name on a Manhattan concert hall and a Los Angeles school, and the wife of a Wall Street banker was roasted for trying to put her name on a small Adirondacks college. Even Bill Gates, who has given billions to battle diseases, is taking lumps in a new book titled No Such Thing as a Free Gift.

Scorn for the rich and powerful dates at least to the Gilded Age heyday of Rockefeller and Carnegie, but experts who track philanthropy say the spate of indignation this year is not surprising when even academics and presidential candidates rail against the privileges of the so-called 1 per cent.

“We've always had this very mixed attitude toward very wealthy people giving their money away,” said Leslie Lenkowsky, an Indiana University professor who studies philanthropy. “It's a long, drawn-out controversy. Our concerns about equality and inequality are bringing it back to the surface today.”

Critiques vary, but they tend to revolve around allegations of vanity for seeking credit, futility for giving to less-deserving beneficiaries or simply acting like an arrogant rich person.

Media mogul Geffen, a prolific philanthropist for the arts, AIDS and other causes, has been accused of a bit of each after two recent gifts, including US$100 million this month to create the Geffen Academy at UCLA to serve the children of faculty, among others. The gift — aimed in part at attracting top talent to the college and its medical school, which is named for Geffen — has generated critical headlines like this one in LA Weekly: “Let's All Watch David Geffen Light His Money on Fire.”

Placing a rich person's name on a building in return for a big donation is an established practice in the philanthropy playbook that can be a way to honour a loved one or encourage other donations. While mocked recently as “Philanthro-me” and “Egonomics” by social commentators, money-for-naming transactions can be mutually beneficial. Benefactors get their name in history books — or at least on Google Maps — and recipients get cash infusions for pressing projects.

For instance, New York's Lincoln Centre received US$100 million toward massive renovations for Avery Fisher Hall from Geffen in a deal that renamed the venue to David Geffen Hall this month. But that happened only after Lincoln Centre paid US$15 million to the family of Fisher, a philanthropist who died in 1994, to clear the way to the renaming.

Geffen’s gift was lauded as transformative by Lincoln Centre administrators and elsewhere criticised as self-aggrandising.

But the reaction was muted compared with the buzz saw started this summer by Joan Weill, the wife of billionaire former Citigroup CEO Sanford Weill.

She offered US$20 million to Paul Smith’s College in New York's Adirondacks — but only if the small college changed its name to the Joan Weill-Paul Smith’s College. Outraged alumni cried foul. The deal was likened to bribery and a betrayal of the college's history.

A court eventually ruled that the bequest that established the college barred the name change. Weill chose not to give the US$20 million.

Alumni took to Facebook to excoriate the proposal, underscoring the role social media can play in amplifying controversies. Best-selling author Malcolm Gladwell started one such debate this summer after hedge-fund billionaire John Paulson gave US$400 million to Harvard’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences by tweeting: “It came down to helping the poor or giving the world's richest university $400 mil it doesn't need. Wise choice John!”

Paulson's defenders argue the donation will fund beneficial innovations and, besides, it’ his money.

Sharp critiques of the “1 per cent” have been commonplace since the first Occupy Wall Street protest four years ago. Sociologist Linsey McGoey goes as far as to question the strategies and influence of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the world's largest charitable foundation, in No Such Thing as a Free Gift. McGoey credits the Gateses for doing good, such as seeking to eradicate malaria and other disease, but takes issue with their approach to global health problems.

The contemporary complaints would be familiar to people in the days of when “robber barons” — the 1 per cent of their time — wielded immense wealth and power. It can be painful for people fighting for clean water or fair housing to see the Fisher family get $15 million so Geffen can put his name on a hall, said Marian Stern, who teaches at New York University's Center for Philanthropy and Fundraising.

“I see the parallels here as not so much that people are critical of the gifts per se, but perhaps the power behind it,” Stern said, “that the donors are dictating the conversation and also really influencing public policy.”