Three vaccines prevent Zika infection in monkeys as trial in humans gets underway

One day after US health officials announced an early start to a clinical trial to test a Zika vaccine in humans, researchers reported in the journal Science that three different types of vaccines designed to block the virus all worked to perfection in monkeys.

The three experimental vaccines had already proven effective in mice, and their success on rhesus monkeys is “raising optimism for the development of a (Zika) vaccine for humans,” the study authors wrote.

With more than 50 countries and territories battling active Zika outbreaks, the need for a vaccine is clear. Hundreds of thousands of people have been infected, including more than 6,400 people in the US and its territories.

Although most infections cause only mild symptoms at best — including fever, rash, headache and joint or muscle pain — women who contract the virus while pregnant put their unborn children at risk of microcephaly. Affected infants are born with small heads and often experience neurological problems and cognitive deficits as they get older.

“A safe and effective vaccine to prevent Zika virus infection and the devastating birth defects it causes is a public health imperative,” Dr Anthony S. Fauci, director of the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in a statement.

The vaccines assessed by researchers from the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Harvard Medical School and elsewhere use three different methods to generate an immune response in patients.

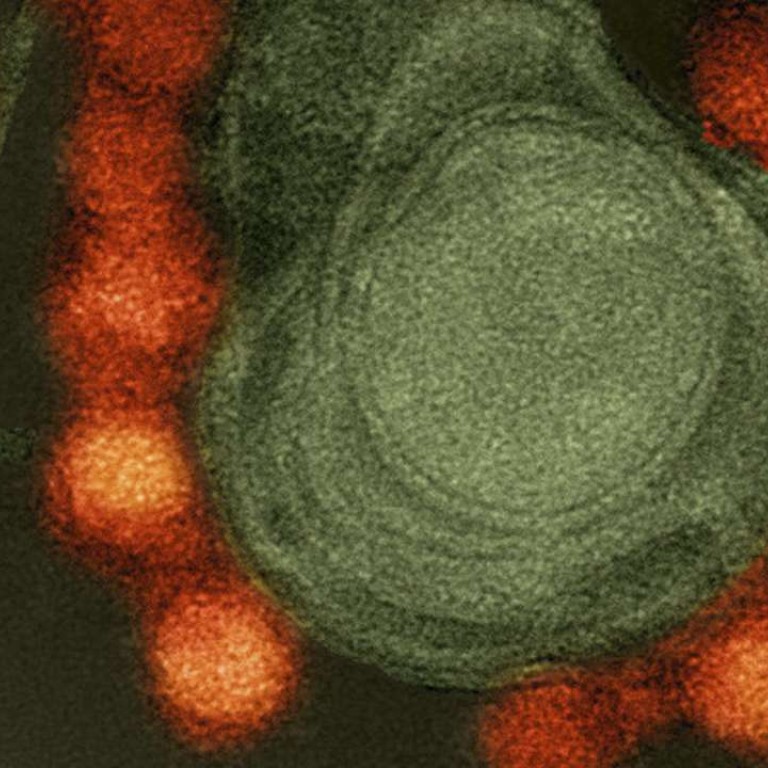

The first of them used a purified and inactivated version of the virus, which was too disabled to cause an infection but still caused the monkeys’ immune systems to make antibodies capable of fighting Zika. When deliberately exposed to the virus, none of the eight monkeys that received two doses of the vaccine showed any sign of infection. However, the eight monkeys that got the placebo became sick for about a week.

Next, the researchers extracted antibodies from the vaccinated monkeys and infused them into four other unvaccinated monkeys. Two of the animals received a lower dose of antibodies and experienced “a blip” of infection when exposed to the virus. The other two monkeys that got a higher dose of the antibodies showed no sign of infection, according to the study.

The other two vaccines — a DNA vaccine and a so-called adenovirus vector-based vaccine — exposed monkeys to fragments of DNA that the Zika virus uses to make its outer coat. Each version was tested in four monkeys, and another group of four monkeys received a placebo.

A single shot of the adenovirus vaccine prompted recipients to make Zika-fighting antibodies two weeks after the injection. The DNA vaccine required two shots — an initial injection and a booster four weeks later — to spark a robust antibody response.

After being exposed to Zika, monkeys that got either type of vaccine had “complete protection” against the virus. However, all of the monkeys that got the sham vaccine became infected with the virus.

“These data support the rapid clinical development of (Zika virus) vaccines for humans,” the study authors concluded.

The vaccine being tested in people in the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases trial is also a DNA vaccine. It contains genes that cause a person’s cells to make Zika virus proteins. Once those proteins are assembled, the body’s immune system should respond by making antibodies and T cells capable of neutralizing the Zika virus. That way, if an actual Zika infection occurs, the body will be ready to fight it.

The vaccine itself can’t cause an infection because the Zika proteins it prompts the body to make “do not contain infectious material,” according to the NIAID.

A similar approach was used in an experimental vaccine for West Nile virus. A preliminary clinical trial found that it safely prompted an immune response.

The Zika vaccine will be tested in 80 volunteers who will be randomly assigned to one of four groups. All of them will get the vaccine at their first visit, using a device that pushes medicine directly into the arm without requiring a needle.

Members of the four groups will receive one or more follow-up doses over various periods of time. Each time a dose is administered, volunteers will be monitored by a doctor for at least 30 minutes.