Publish and be damned: Turkish media resisted coup, but it won’t win any favours from government

At the Dogan Media Centre, a sleek glass building in Istanbul that houses some of Turkey’s major media outlets, the failed coup arrived just before dawn Saturday with the low drone of a Black Hawk helicopter setting down in a nearby parking lot.

Minutes later, 14 soldiers led by a small cadre of officers entered the building, quickly splitting into two smaller groups to take over various media outlets, including the Hürriyet Daily News, and the television stations CNN Türk and Kanal D.

The soldiers had one demand - stop publishing or broadcasting - and other than that they said little. The cameras kept rolling, however, as newsroom staff members pulled out their smartphones and the producers put up a ticker that read, “Soldiers have entered CNN Turk studios”.

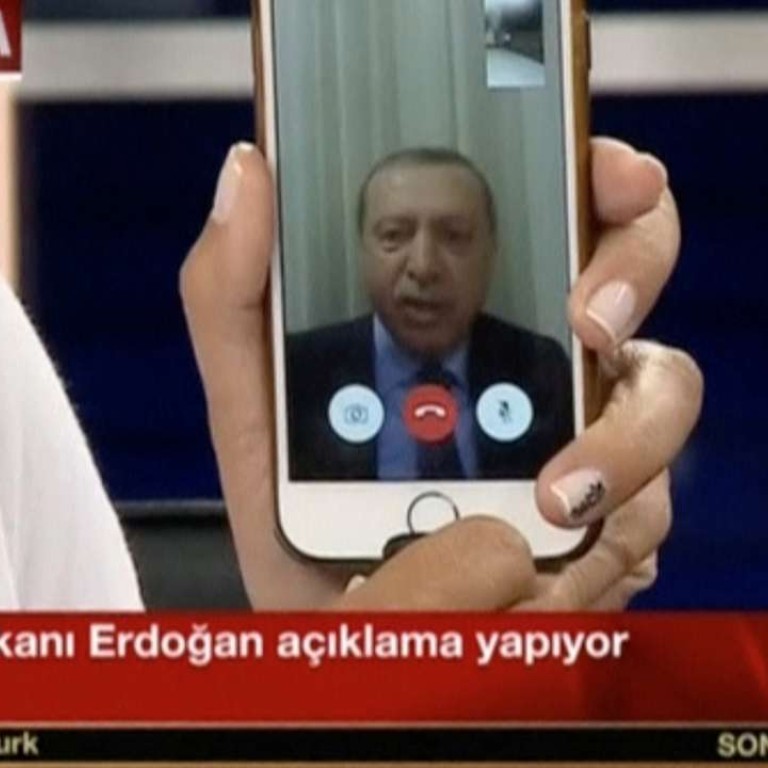

Yet despite a moment of seemingly mutual understanding between Erdogan and the independent Turkish media - best captured in a surreal moment when an Ankara bureau chief for CNN Turk let Erdogan FaceTime his nation in the throes of the coup d’état - some Turkish journalists are wary over what the unrest will entail for their profession and ultimately their country.

Murat Yetkin, the editor in chief of Hürriyet Daily News, was at his desk when seven soldiers burst into the atrium of his building Saturday morning, pointing rifles at journalists and telling them to “stop their work and get out.”

Outside the media centre, Yetkin couldn’t help noticing that a growing crowd of anti-coup protesters contained many of the same faces from an incident in September, when armed throngs who backed Erdogan had attacked his newsroom with Molotov cocktails because of its reporting on Erdogan and his government.

“There’s no reason to be optimistic about this situation,” Yetkin said. “But you cannot correct bad with worse. We have a lot of problems, but that’s no reason to be supportive of a military coup.”

CNN Turk, part of the Dogan Media group that owns the Hürriyet Daily News, also had a history of conflict with the Erdogan government. But journalists said that feud was put aside when soldiers stormed the building.

The Dogan Media group is part of conglomerate known as Dogan Holding, which has had several disputes with Erdogan’s government. In 2009, for instance, the conglomerate was fined US$2.5 billion for unpaid taxes. But critics said the judgement was payback for the group’s coverage of corruption allegations against members of the president’s inner circle.

In May 2015, Erdogan accused the owner, Aydin Dogan, of being a “coup lover” and labelled the group’s columnists as “charlatans.”

Dogan came to Erdogan’s defence Sunday, criticising the coup attempt in a statement published on the Hürriyet Daily News under the headline, “Let’s defend democracy together.”

Dogan said the country had “survived a possible disaster with the solidarity of the state, the nation, politics and the media.” He went on to say people in Turkey, whatever their political differences, should defend democracy and come together as a nation.

For Erdem Gül, the Ankara bureau chief of the newspaper CumHürriyet, Erdogan is unlikely to thank his former critics for their support during the coup, and its suppression probably will mean further restrictions on press freedom.

“The government controls a big part of the media and for those parts which it couldn’t control, they are under the threat of imprisonment or being investigated,” Gül said in a phone interview. “For these reasons there is a lot of concern that Turkey is now heading toward even more authoritarianism.”

In May, Gül was sentenced to five years in prison, along with a similar sentence for his colleague Can Dundar, for a report on Turkey’s attempt to ship arms to Islamist rebels fighting the Syrian government. Both journalists were acquitted of espionage charges and their cases are currently being appealed.

But more than 30 other journalists are in prison, Gül said, and the Committee to Protect Journalists has said Turkey is one of the “worst jailers of journalists worldwide.”

“In the aftermath of the attempted coup, we urge the Turkish government to allow journalists to report on news events freely and independently,” CPJ Europe and Central Asia Programme Co-ordinator Nina Ognianova said in a statement. “And to do its utmost to guarantee the safety and security of all journalists.”