With landmark UK embassy planned for East London, China rides the river of history full circle

The new diplomatic mission will occupy the former Royal Mint, near the site of London’s original Chinatown by the Thames

London is getting a new landmark on an historic site – one of the biggest Chinese embassies in the world.

Beijing announced on May 18 it was leaving its premises in Portland Place in the West End after 150 years and moving its diplomatic representation to the iconic former Royal Mint.

Situated in front of the Tower of London, on the teeming crossroad to Tower Bridge over the River Thames, the huge palace – built in 1810 – and its surrounding offices have remained empty since the last gold sovereign was struck there in 1975.

“I am confident that after the renovation, the new premises of the Chinese Embassy will become a new landmark in London and a new face of China in the new era,” said Ambassador Liu Xiaoming when the move was announced.

At the moment there is not much to see. The buildings are hidden behind a six-metre wall and hoarding with a pair of huge red lips announcing a new shopping centre on the 2.2-hectare site.

History is like a river that flows steadily and firmly forward. Follow and keep abreast with its current, we can ride the tide of the times

That was the original plan of developers Delancey and real estate company LRC when they bought the site from the Crown in 2010 – until they sold the lot to China.

With planning permission already in place for retail outlets, it is also expected there will be a cultural centre on the site to sit alongside 600,000 square metres of office space.

Beijing has not said how much it paid for the property, but the price tag is estimated to be more than £200 million (US$292 million).

Estate agents Savills, who helped with the deal, say once completed in two years’ time, the fortress-style embassy and cultural hub would be worth £750 million.

Known in the Middle Ages as Eastminster, the site where the embassy will be, is expected to be a major economic boost to the London Borough of Tower Hamlets where it is situated.

The whole area is still in the throes of regeneration that began in the 1980s with the development of Canary Wharf, and gathered pace when China handed the baton ten years ago to the UK for the 2012 Olympics that were also held on the site in the east of the borough.

Much of the chatter about the new Chinese embassy in London, where in 1877 China opened its first diplomatic representation abroad, has been about the fact that it is in East London.

The US Embassy recently moved out of the West End but built its new glass fortress further west.

But for China, East London makes strategic sense.

To less fanfare, the Chinese property company ABP has also bought what used to be the Royal Albert Docks, almost 2km of riverfront for offices, homes and shops to rival Canary Wharf.

The scheme is due to open in March next year, when the UK is scheduled to leave the European Union.

“We recognise that the vote for Brexit is the result of the people, the government and the parliament wanting to have the greater degree of dependence outside the EU to decide its own destiny,” ABP chairman Xu Weiping said in an interview with the UK financial newspaper City AM.

“As a result China is even more important in this context. Working with China is different from being part of the EU because there will be no regulations and limits imposed on the companies doing trade with China.”

Both Xu and the Chinese Ambassador to the UK talked about a new “golden era” of Anglo-Chinese relations.

Ambassador Liu described the purchase of the old Royal Mint that first went into production making gold medals for English soldiers returning from the 1812 Battle of Waterloo with France, as “a fresh golden fruit of the China-UK Golden Era”.

Referring to the River Thames that the new embassy will face he said: “History is like a river that flows steadily and firmly forward. Follow and keep abreast with its current, we can ride the tide of the times.”

At around the same time as the presses of the old Royal Mint were whirring into production, the East India Company was beginning to trade with China.

As that trade was established and the East India dock was opened to receive the ships, London’s East End district, then a dockside slum now a desirable area in the shadow of Canary Wharf, became home to London’s first Chinatown.

It was the first port of call of Chinese seamen, and for many the last.

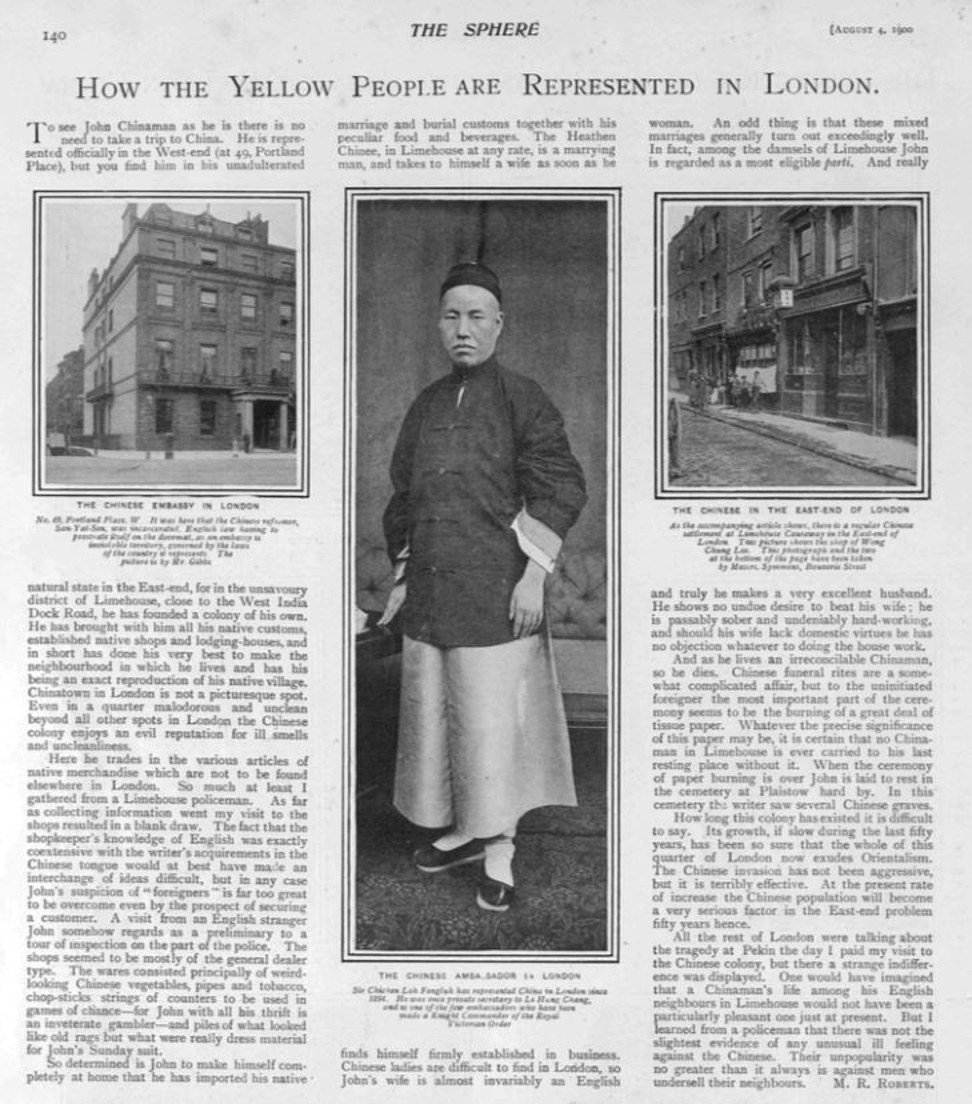

In an article published in The Sphere newspaper in August 1900, journalist M.R Roberts wrote how “John Chinaman” founded a “colony of his own” in the area he described as “malodorous and unclean beyond all other spots in London.”

He described the shops as selling “weird-looking Chinese vegetables, pipes and tobacco, chop-sticks, strings of counters to be used in games of chance” and said the “whole of the area exudes Orientalism.”

The presence of Chinese people in the area around the London docks that triggered a wave of Sinophobia in popular culture, encapsulated by the “evil” character of Fu Man Chu, the villain of what are now seen as deeply racist novels by the writer Sax Rohmer.

Unfounded rumours of a “white slave trade” being operated out of the Chinese laundries there swirled around the London fog. The district’s opium dens were legendary.

It was in one such establishment in Limehouse that Sherlock Holmes found Dr Watson in Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Man with the Twisted Lip.

Local people however had a different view. There was never any real evidence of a white slave trade, and because most of the Chinese immigrants were men, they quickly married poor local women, and gained a reputation as good husbands.

In 1919 an American silent movie was set in Limehouse called Broken Blossoms that told the story of how a Chinese man saved an English girl from her drunken abusive father.

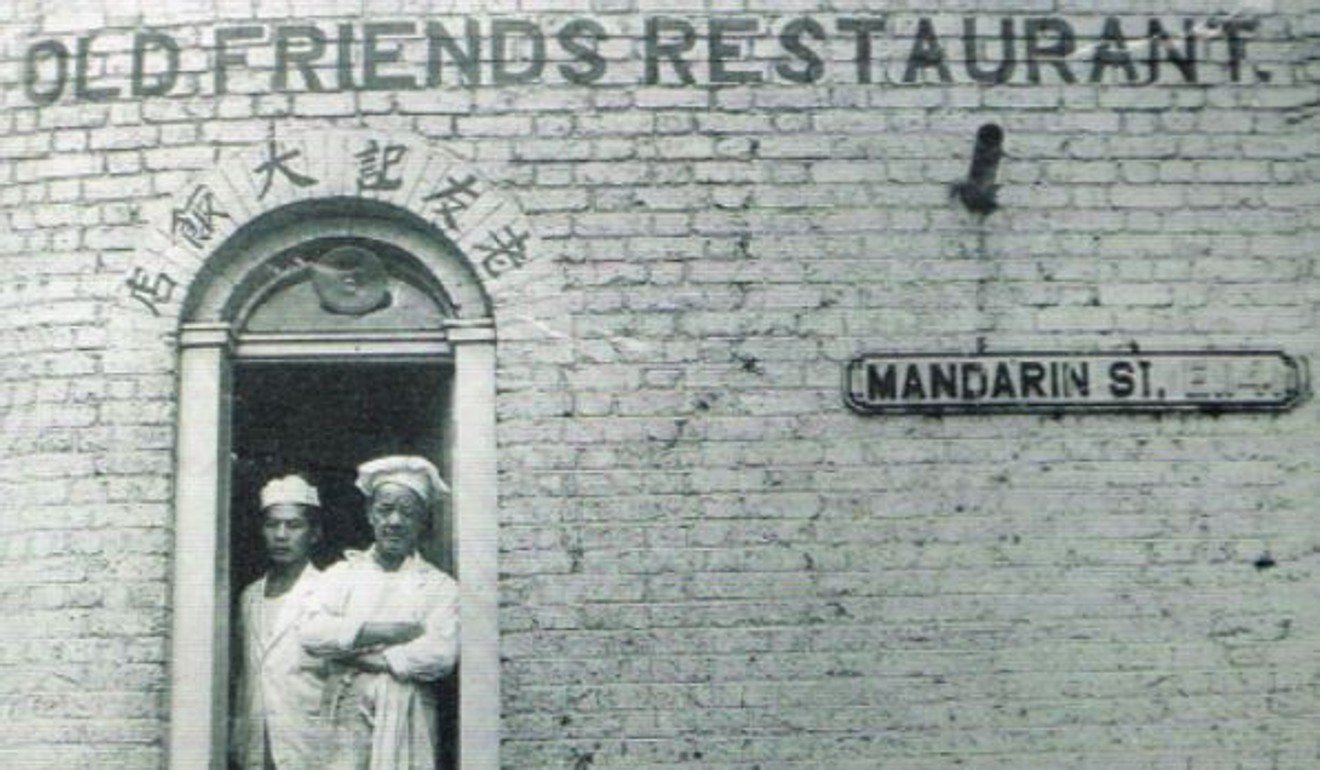

Chinese laundries opened up, and a now mythic restaurant called Good Friends where it is said the English working class had their first taste of Chinese food.

Several other “Friends” restaurants followed with names like “Old Friends”, “Good Friends” and one, still remaining, “Local Friends”.

Fears of a Chinese population explosion did not materialise. A slump in shipping entering the East India docks triggered the exodus, as did heavy bombing by the Luftwaffe during the second world war, and Soho became London’s new Chinatown.

There is still a Chinese community centre and Chinese school in the area to serve the community, the numbers swelled by Chinese Vietnamese and a new generation of Chinese expatriates, bankers in Canary Wharf or students at the nearby Queen Mary’s College.

The ghosts of the old Chinese presence can be found in some of the area’s street names – Canton Street, Pekin Street, and even Noodle Street.

A bronze dragon statue was erected in Limehouse in 2000 to mark the spot where Chinatown once began, now mostly hidden by a tree.

But older East End residents still remember the old Chinese quarter with fondness.

Photographer Tony Lam, 50, grew up in Limehouse where his father came from Ting Kok village to work as a chef in 1959.

“In the 70s there was still a small Chinatown, mainly the Friends restaurants. I remember some of the older people coming to play Mahjong at the house. But once the Chinese had established themselves they tend to move out.”

There are still a couple of Chinese community centres to serve the elderly, and an independent Chinese school, but the majority of the Chinese community in Tower Hamlets now, already the third biggest Chinese population in London after Westminster and the City of London, are more recent arrivals.

In its heyday, Limehouse’s Chinatown was probably one of the most famous places in London, with police offering tours to add to the area’s edgy reputation.

When the new Embassy opens, and hundreds of diplomats arrive, the Chinese will again be a major draw.

The hope is that it will bring business and jobs in an area that still also hosts large swathes of economic deprivation, including the highest child poverty rate in the country, cheek by jowl to some of London’s most expensive real estate, of which China has just bought one of the crown jewels.