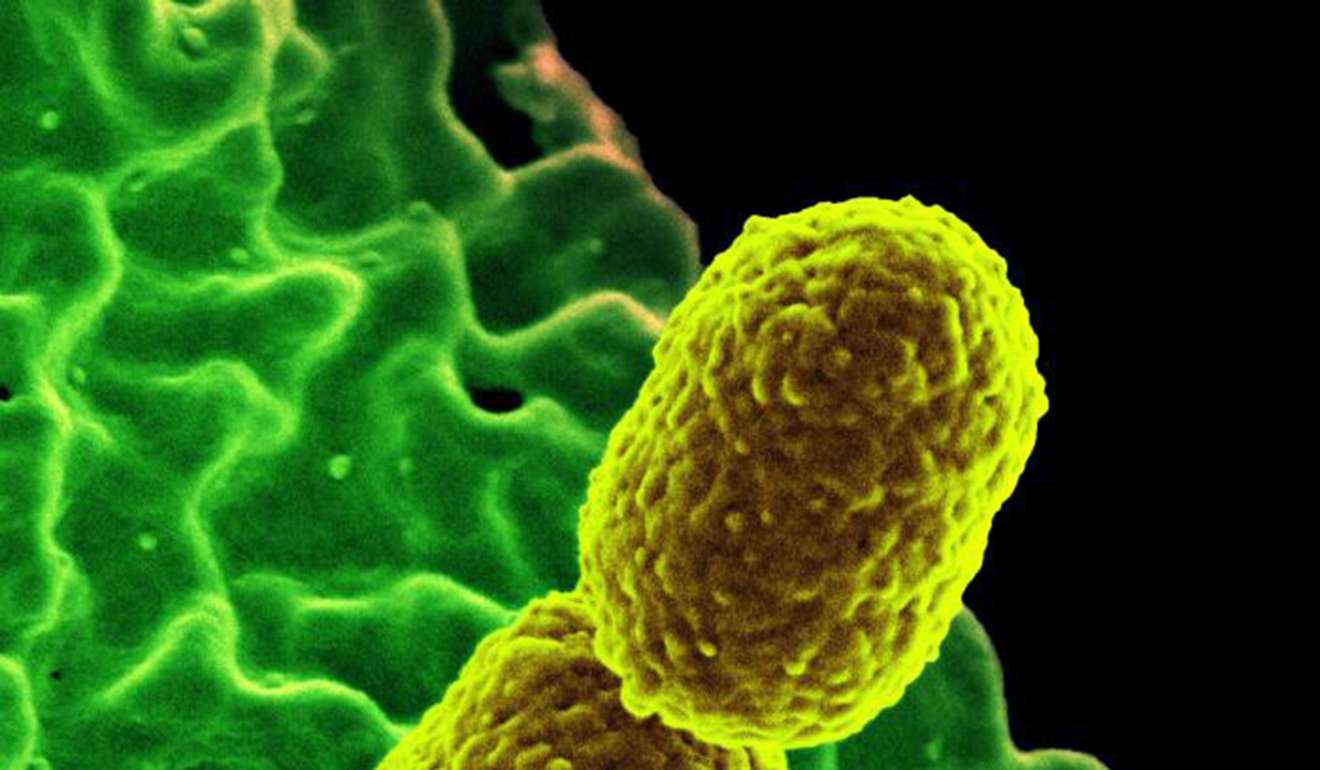

WHO warns of 12 superbugs which can kill millions of people

The highest priority is a bacteria called CRE which US officials have dubbed ‘nightmare bacteria’ and can kill up to 50 per cent of infected patients

The World Health Organisation announced its first list of antibiotic-resistant “priority pathogens” on Monday, detailing 12 families of bacteria that agency experts say pose the greatest threat to human health and kill millions of people every year.

The list is divided into three categories, prioritised by the urgency of the need for new antibiotics. The purpose is to guide and promote research and development of new drugs, officials said.

Most of the pathogens are among the nearly two dozen antibiotic-resistant microbes that the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention warned in a 2013 report could cause potentially catastrophic consequences if the United States didn’t act quickly to combat the growing threat of antibiotic-resistant infections.

“This list is not meant to scare people about new superbugs,” said Marie-Paul Kieny, an assistant director-general at WHO. “It’s intended to signal research and development priorities to address urgent public health threats.”

Superbugs that the WHO considers the highest priority are responsible for severe infections and high mortality rates, especially among hospitalised patients in intensive care or using ventilators and blood catheters, as well as among transplant recipients and people undergoing chemotherapy. While these pathogens are not widespread, “the burden for society is now alarming,” she said.

Included in this highest-priority group is CRE, or carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, which US health officials have dubbed “nightmare bacteria.” In some instances, it kills up to 50 per cent of patients who become infected. An elderly Nevada woman who died last year contracted an infection caused by CRE that was resistant to all 26 antibiotics available in the United States.

Also included in this critical group is Acinetobacter baumannii; the infections tied to it typically occur in ICUs and settings with very sick patients. Also listed is Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which can be spread on the hands of health-care workers or by equipment that gets contaminated and is not properly cleaned.

WHO’s list follows a summit on superbugs that world leaders held last fall - only the fourth time they had addressed a health issue at the UN General Assembly.

The list’s second and third tiers - the high and medium priority categories - cover bacteria that cause more common diseases, such as gonorrhea and food poisoning caused by salmonella. While they’re not associated with significant mortality rates, “they have a dramatic health and economic impact, particularly in low-income countries,” Kieny said.

Although there has been renewed interest and research investment in antibiotics because of the growing threat that antibiotic resistance poses, much of the work is more focused on antibiotics with a broad range, she said. “We have to focus specifically for a much smaller range of bacteria,” specifically targeting the three highest-priority pathogens, Kieny said.

Drug companies have also tended to focus more on gram-positive bacteria that tend to colonise the skin of healthy individuals and generate less resistance, said Evelina Tacconelli, who heads the infectious diseases division at the University of Tübingen in Germany, which helped develop the WHO list. By comparison, gram-negative bacteria more frequently colonise intestinal reservoirs and can cause sepsis and severe urinary tract infections, especially among elderly patients.

There have been no new classes of antibiotics discovered that have made it to market since 1984, according to the Pew Charitable Trust’s antibiotic-resistance project. And there aren’t enough drugs in the pipeline to meet future needs, Allan Coukell, senior director of health programmes at Pew, said Monday.

Of the 40 antibiotics in clinical development in the United States, “fewer than half even have the potential to treat the pathogens identified by WHO,” he said. “And based on history, most of those will fail to reach the clinic for reasons of efficacy or safety. So the outlook is grim.”

Historical data show that generally only one of five drugs that reach the initial phase of testing in humans will receive approval from the Food and Drug Administration. Developing antibiotics to treat highly resistant bacterial infections is especially challenging because only a small number of patients contract these infections and meet the requirements to participate in traditional clinical trials.

In the United States, antibiotic-resistant infections kill an estimated 23,000 Americans each year, according to the CDC. Global estimates are difficult because there is no uniform way to include antimicrobial resistance in causes of death. But experts say that drug-resistant infections, especially those caused by the WHO’s highest-priority pathogens, double or triple the risk of death.

“We are talking about millions of people affected,” Tacconelli said.