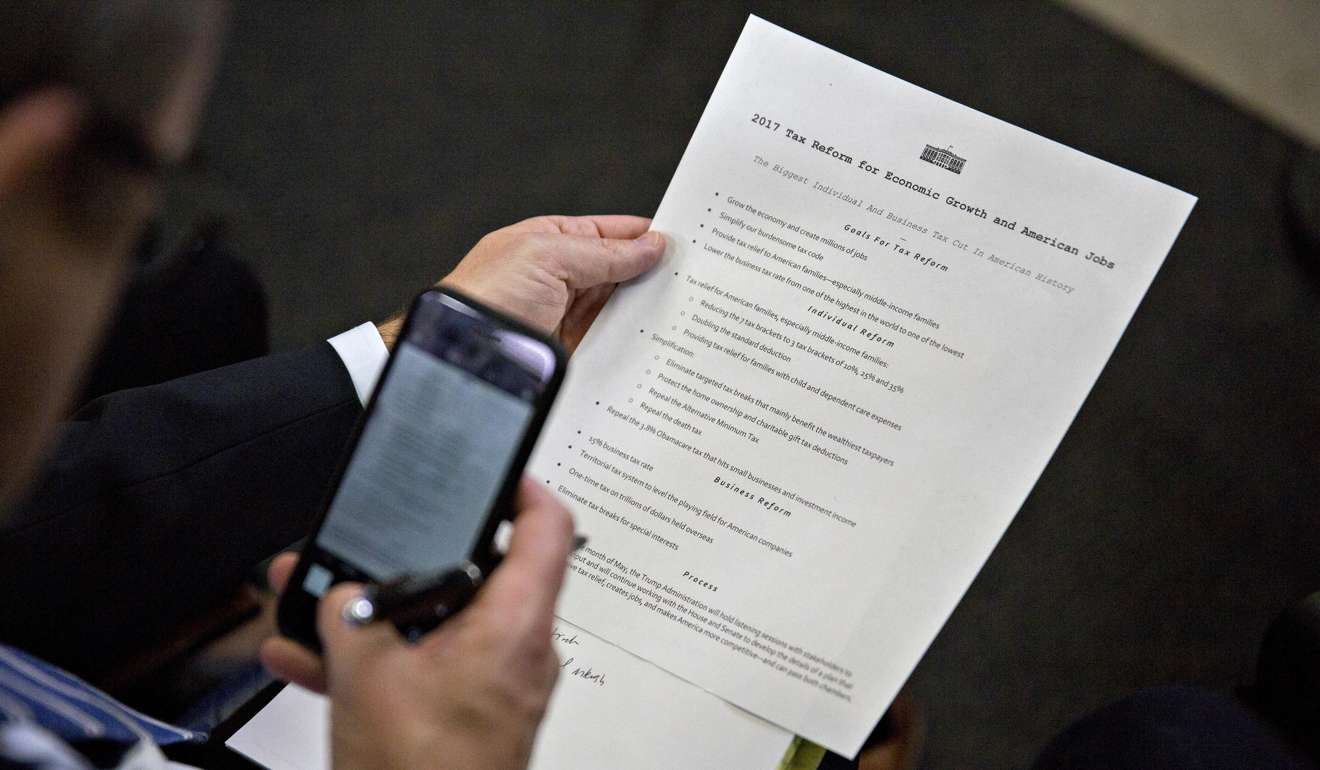

Analysis | Deciphering Trump’s tax-cut plan: only 200 words and seven numbers, but huge in ambition

US President Donald Trump’s team boasted Wednesday of its tax-cut plan that they said would lighten Americans’ financial burdens, ignite economic growth and vastly simplify tax filing.

Yet the proposal was short of vital details, including how it would be paid for - it was less than 200 words long and contained just seven numbers.

And based on the few specifics spelled out so far, most experts suggest that it would add little to growth while swelling the budget deficit and potentially handing large windfalls to wealthier taxpayers.

Trump’s plan would replace the current seven income-tax brackets with three, and the top bracket would drop from 39.6 per cent to 35 per cent. It would also slash the corporate rate from 35 per cent all the way to 15 per cent, a boon to most companies even though many don’t pay the full tax now. With tax credits and other loopholes, most corporations pay closer to 20 per cent, according to calculations by JPMorgan.

Perhaps the most contentious plank would enable taxpayers with business income — including those wealthy enough to pay the top tax rate — to instead pay the new 15 per cent corporate rate. That’s because Trump would apply the corporate rate to “pass through” businesses. Pass-throughs include partnerships such as law firms and hedge funds as well as most small businesses — from the local florist to the family-owned restaurant on Main Street.

What’s more, some privately held large companies — including Trump’s own real estate empire — are structured as pass-throughs and would benefit, too.

“This is about economic growth, job creation, America first, and that’s what [Trump] cares about,” White House National Economic Council Director Gary Cohn said. “Our tax plan is a big leg of that stool. It’s a big leg. And in many respects, he thinks it’s the most important leg.”

The plan now must navigate a legislative and political gantlet on Capitol Hill that has killed numerous other efforts to rework the tax code.

“It’s a great plan,” Trump said at the White House on Wednesday. “It’s going to put people back to work.”

The proposal also eliminates the estate tax - referred to by some opponents as the “death tax” - a levy on property including cash and real estate transferred from deceased individuals to their heirs.

But with the tax plan limiting most deductions, it could expose more of an average American household’s income to taxes.

It’s hard to say precisely who would benefit most because the administration has released so few details. The three new income tax rates would be 10 per cent, 25 per cent and 35 per cent. But Cohn, and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, weren’t ready to say at what income levels these new rates would kick in.

The theory is clear - by making corporations more profitable, the Trump administration hopes to encourage more business spending on equipment, from computers to factories and machinery.

Doing so, in turn, could make the economy more efficient and accelerate growth and hiring. Growth has been stuck at about 2 per cent a year since the recession ended in 2009. Mnuchin says the administration wants to accelerate it above 3 per cent, a pace it hasn’t touched since 2005.

The obvious risk of the plan is that the government’s budget deficit could explode, offsetting many of the benefits for the economy

The corporate tax cuts are also intended to encourage more businesses to stay in the United States, which now has the highest corporate rate among the advanced economies.

Many large corporations are enthusiastic about lower rates and say they support the elimination of loopholes, which both reduce revenue and make taxes more complicated.

“Simplifying the tax code as well as getting the rate to a point of being able to compete on a global scale is certainly something that we support,” an executive at Boeing said on a conference call about the company’s earnings earlier Wednesday.

Aside from most large companies, many partnerships and small businesses would benefit from the corporate rate cut because they are structured as pass-throughs, an ungainly moniker that derives from the fact that they pass on their profits to their owners.

Those owners now pay individual income tax rates, which top out at 39.6 per cent. With the pass-through rate dropped to 15 per cent, those taxpayers would receive an enormous tax cut.

The Trump team stressed the benefits that might flow to small businesses. But the richest windfalls would flow to the wealthy — lawyers, hedge fund managers, consultants and other big earners. Nearly 75 per cent of pass-through income flows to the 10 per cent wealthiest taxpayers, according to the liberal Centre on Budget and Policy Priorities.

The administration is also proposing to tax only corporate income earned in the United States. This is known as a “territorial” system. It would replace the current worldwide system, under which corporations pay tax on income earned in the US and overseas.

Yet companies can avoid the tax if they keep their foreign earnings overseas. That’s led many businesses to keep hundreds of billions of dollars outside the United States.

Mnuchin said Trump’s plan would encourage corporations to return the money to the US and invest it in plants and equipment. Yet some analysts argue that corporations might instead use the money to simply pay dividends to shareholders.

The obvious risk of the plan is that the government’s budget deficit could explode, offsetting many of the benefits for the economy, economists say. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget’s rough estimate puts the loss of revenue at US$5.5 trillion.

Mnuchin argued that the tax cuts would spur faster economic growth, which, in turn, would produce more tax revenue. And the elimination of tax deductions and other loopholes would raise revenue as well, he contended.

But the Trump team offered no details on which deductions would be dropped — a move that would likely spark ferocious opposition from the beneficiaries of those deductions. And most economists don’t accept the notion that growth would accelerate enough to offset the lost revenue.

Alan Cole, an economist at the right-leaning Tax Foundation, calculates that the corporate tax cuts alone would lower government revenue by US$2 trillion over 10 years. That would require growth to accelerate nearly a full percentage point, to 2.8 per cent a year, from its current level. Yet Cole forecasts that growth would increase only 0.4 of a percentage point annually.

Additional reporting by the Washington Post and Agence France-Presse