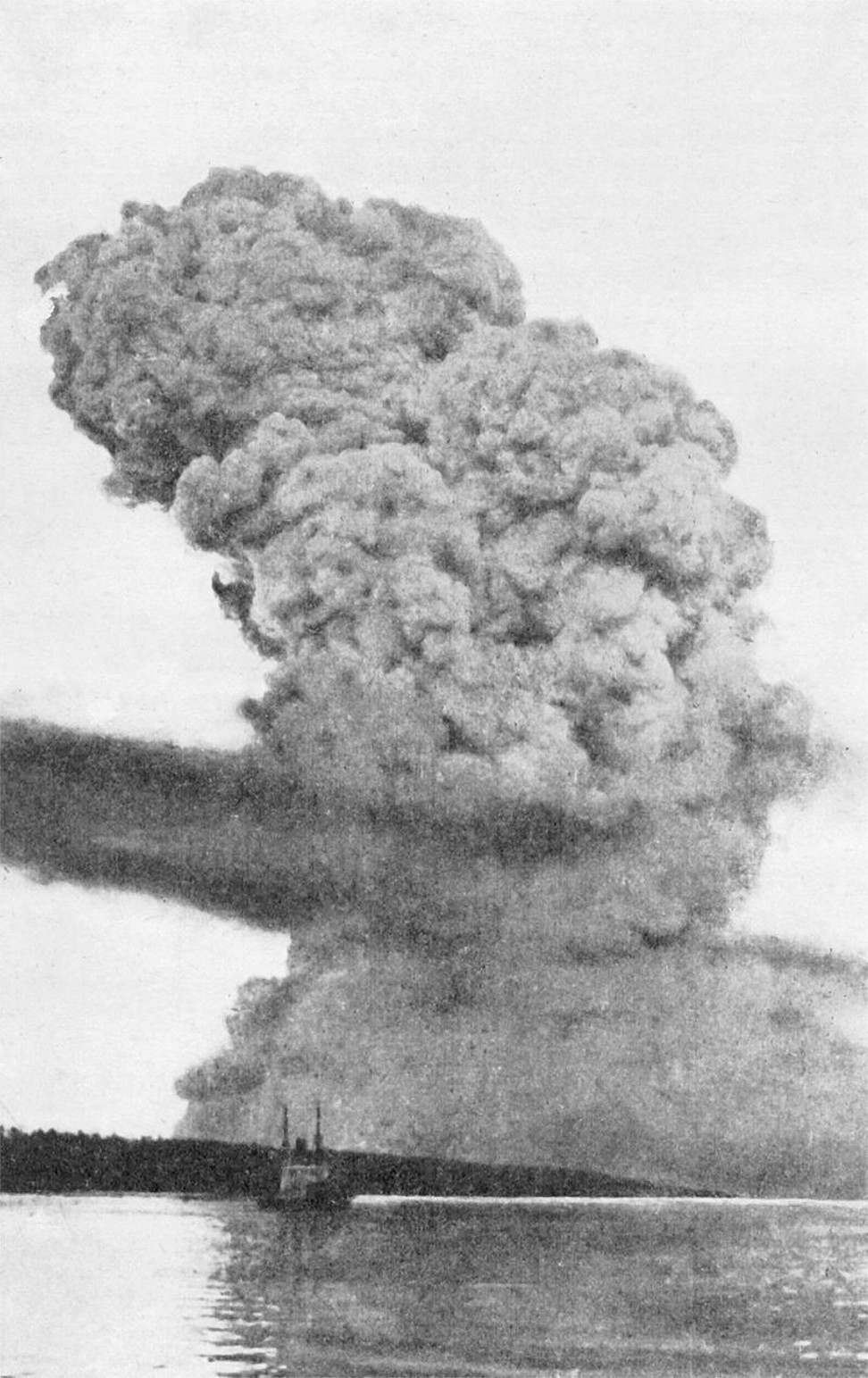

Remembering the biggest pre-atomic explosion, that killed 2,000 and left Halifax in ruins

The Halifax Explosion of 1917 took place when two ships collided - one of them

was carrying 3,000 tonnes of high explosives

On the bright, freezing morning of December 6, 1917, a French captain steered his ship, the SS Mont Blanc, up the channel leading to the piers of Halifax, Canada’s major Atlantic port. Just after 8.30am, as the ship steamed into the bottleneck between the ocean and the inner harbour, he looked up to see something that shouldn’t have been there: the SS Imo, a Norwegian freighter, heading straight toward him on his side of the skinny narrows.

The two massive ships blasted their whistles, attempted a few futile evasive manoeuvres and then collided, bow to bow. It was not a fatal blow.

“In marine terms, what happened was a fender bender,” said historian Roger Marsters. “It was only the character of the cargo that made it what it was.”

What the Imo had rammed was a 3,000-tonne floating bomb. The Mont Blanc was crammed with munitions, bound for the war raging in Europe. Its holds were crammed with 2,500-tonnes of TNT and picric acid. The decks were crowded with barrels of high-octane benzol.

Sombre ceremonies were held in Halifax on Wednesday to mark the 100th anniversary of what remains the worst human-made disaster in Canadian history.

“Halifax” became the standard of blast comparisons for decades, unsurpassed as an explosive disaster until Hiroshima replaced it in 1945.

The horror of crushed schools and victims stumbling bloodied and blown naked through the rubble has stamped the city to this day, said Marsters, curator of marine history at the Nova Scotia Museum. “It was a scene reminiscent of New York after 9/11,” he said.

Disaster struck at a boomtime for Halifax, which had seen its population soar with the wartime bustle of supply ships and troop carriers. Deep into first world war, it was home to Canadian and British naval bases, major supply centres and a hospital for returning wounded. The waterfront was crowded when those frantic whistle blasts cut suddenly through the winter chill.

But there was traffic, and the Imo had just steered around a tug boat and an American naval vessel, putting it in Mont Blanc’s path. As the 1km gap closed, both skippers did what they could with their cumbersome ships and it looked at one point as if they would just scrape past each other. But at the last minute, the captain of the Imo desperately threw his engines into reverse. His bow swung, clipping the Mont Blanc a solid blow at the forward hold.

There were sparks.

The Mont Blanc carried no special markings. Almost no one knew what filled her compartments except a few port officers and, of course, her crew. As the barrels of benzol broke open and started to burn, they sprinted to the lifeboats.

Rowing like mad, they reached shore within minutes. They continued running, shouting warnings to all they passed, but shouting them in French.

“Few people in Halifax spoke French at that time,” said Marsters. “More people were running toward the waterfront to see the fire.”

The helpless Mont Blanc drifted toward Pier 6, billowing black smoke. Halifax firefighters raced toward it. The crew of the Imo watched from their own damaged ship. Windows all around the harbour filled with faces peering through the glass at the drama unfolding. The minutes ticked by.

A hundred years on, the hands on the town hall tower clock remain broken forever at 9.05am. Later seismic studies would pin the exact time of the blast at 9:04.35.

The initial shock wave levelled the surrounding blocks, including a densely packed industrial area called Richmond and, on the other shore, a long-time native settlement of the Mi’kmaq people. More than 1,600 houses were instantly destroyed, 12,000 more were damaged.

To this day, gardeners dig up hunks of metal from the blast. A family recently brought a piece of hull to the maritime museum that had long served as a boot scrape on their porch.

“I remember climbing on it when I was a child,” said Marsters.

The Mont Blanc was no more. Ironically, all its crew survived except for one sailor who was felled by shrapnel. The bridge crew of the Imo was killed, including its captain and the pilot. Two helmeted deep-sea divers working at the harbour bottom made it; their tenders at the surface did not.

In the hours that followed, Halifax proved itself uniquely ready to help itself. Thousands of military members, merchant sailors, lumbermen and other flinty locals poured into the blast zone. Army nurses, accustomed to mass casualties, sprang to action. Surgeons operated non-stop, often with nothing but local anaesthesia. Ophthalmologist George Cox removed 79 eyeballs in a 48-hour marathon.

Foreign assistance came within minutes from American and British navy ships. The blast was front-page news around the world and more help arrived within days. Massachusetts dispatched a trainload of doctors, nurses and medical supplies, and to this day the great Christmas tree in Boston Commons is given by Nova Scotia as a thank you gesture.

An initial inquiry laid the blame on the Mont Blanc, particularly its captain and harbour pilot Francis Mackey, for not avoiding such a dangerous encounter at any cost. But later investigations split the blame for navigational errors between the two vessels.

There is reportedly a single living survivor from the day of the blast, Marsters said, a 106-year-old woman. But the event is being well remembered with ceremonies, major exhibits and a new time-capsule to be buried near the waterfront.

The catastrophe, over time, served to further temper Haligonians as a people hardened by the rough weather and big traumas of the high latitudes. It was to Halifax, after all, that the Titanic was bound in 1912.

“This is a North Atlantic port,” Marsters said. “We are no strangers to disaster.”