Analysis | Texas high school had a shooting plan, armed police and practice – and yet 10 people died. Why?

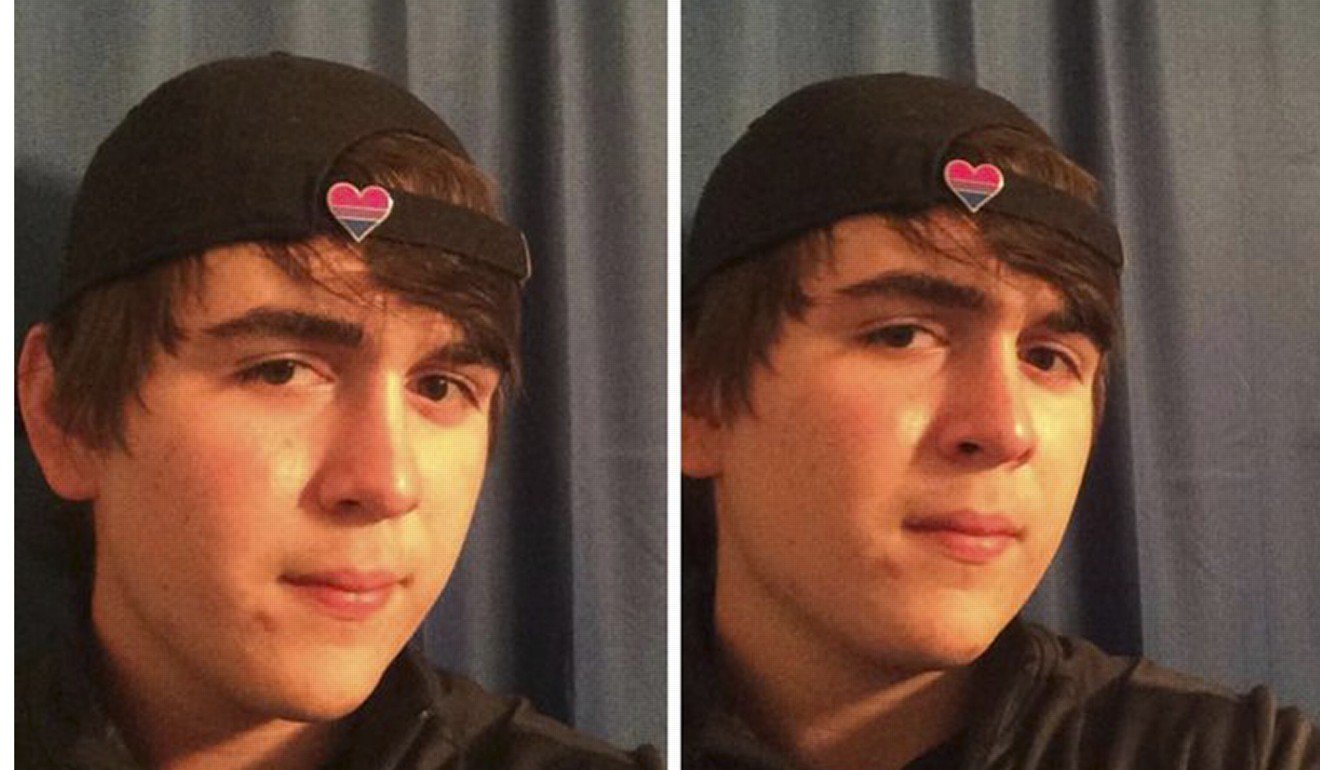

Dimitrios Pagourtzis, a 17-year-old student at the same Santa Fe High School, is being held on two charges: aggravated assault to a public servant and capital murder

They, like so many others, thought they had taken the steps to avoid this.

The school district had an active-shooter plan, and two armed police officers walked the halls of the high school.

School district leaders had even agreed last fall to eventually arm teachers and staff under Texas’ school marshal programme, one of the country’s most aggressive and controversial policies aimed at getting more guns into classrooms.

They believed they were a hardened target, part of what’s expected today of the American public high school in an age when school shootings occur with alarming frequency.

“My first indication is that our policies and procedures worked,” JR “Rusty” Norman, president of the school district’s board of trustees said.

“Having said that, the way things are, if someone wants to get into a school to create havoc, they can do it.”

The mass shooting – which killed 10 people and wounded 10 others in this rural community outside Houston – again highlighted the despairing challenge at the centre of the ongoing debate over how to make the nation’s schools safer.

It also hints at a growing feeling of inevitability, a normalisation of what should be impossible tragedies.

The gunman in Santa Fe used a pistol and a shotgun, firearms common to many South Texas homes, firearms he took from this father, police said.

So there were no echoes of the calls to ban military-style AR-15s or raise the minimum age for gun purchases that came after the school shooting three months ago in Parkland, Florida.

Most residents here didn’t blame any gun for the tragedy down the street. Many of them pointed to a lack of religion in schools.

“It’s not the guns. It’s the people. It’s a heart problem,” said Sarah Tassin, 61.

“We need to bring God back into the schools.”

Texas politicians are pushing to focus on school security – the hardening of targets.

Governor Greg Abbott said he planned to hold round table discussions starting Tuesday on how to make schools even more secure.

One idea he and other state officials mentioned was limiting the number of entrances to the facilities. US Rep. Randy Weber, a Texas Republican, said Congress eventually would consider legislation focused on “hardening targets and adding more school metal detectors and school police officers.”

But the horror in Santa Fe shows there are limits there, too.

Norman said he saw school security as a way to control, not prevent, school violence. And the school district had some practice.

In February, two weeks after the Parkland shooting, Santa Fe High went into lockdown after a false alarm of an active-shooter situation, resulting in a huge emergency response. The school won a statewide award for its safety programme.

“We can never be over-prepared,” Norman said.

“But we were prepared.”

His school board approved a plan in November to allow some school staff to carry guns, joining more than 170 school districts in Texas that have made similar plans. But Santa Fe was still working on it, Norman said.

Staff needed to be trained. Details needed to be worked out, such as a requirement that school guns fire only frangible bullets, which break apart into small pieces and are unlikely to pass through victims, as a way to limit the danger to innocent students.

All of these efforts, Norman said, are “only a way to mitigate what is happening.”

The search for red flags about the gunman’s intentions continued Saturday – another familiar hallmark of school shootings.

Dimitrios Pagourtzis, the 17-year-old student who police said confessed to the shooting, was being held without bond at a jail in nearby Galveston.

Wearing a trench coat, he allegedly opened fire in an art class, stalking through the room shooting at teachers and students, talking to himself.

He walked up to a supply wardrobe where students were barricaded inside, and he shot through the windows, shouting “Surprise”, said Isabelle Laymance, 15.

The gunman shot a school police officer who approached him, then talked with other officers, offering to surrender. The entire episode lasted a terrifying 30 minutes, according to witnesses and court records.

The Pagourtzis family released a statement Saturday saying they are “shocked and confused” by what happened and that the incident “seems incompatible with the boy we love.”

The alleged gunman’s classmates and parents said they saw no unusual signs of trouble before the shooting, though some said he had seemed somewhat depressed in recent months.

Bertha Bland, whose grandson is good friends with Pagourtzis, said she knew the teenager well and described him as “an outstanding kid” and a good student.

Scott Pearson, whose son played football with Pagourtzis, described him as a quiet, normal kid. He didn’t talk to him much when he took him home from football practices, but he never got the impression that he was dangerous.

He noticed that Pagourtzis regularly wore a trench coat but didn’t think much of it.

“Kids do weird stuff,” Pearson said.

“I don’t understand when my son wears a hoodie out in 90 degree heat, either.”

Pagourtzis improved as a football player between sophomore and junior years, moving from second to first string as a defence tackle on the junior varsity squad, according to Rey Montemayor, an 18-year old senior quarterback.

Local and federal officials have revealed little new information about the shooting or the investigation.

So far, investigators have not found any link to terrorism or political extremism in the suspect’s background that would offer a motive for the attack, according to a person close to the investigation.

The evidence recovered in the first day of the probe suggests that the gunman was a disturbed young man without any particular ideology, though it is still early in the investigation and new facts could emerge, the person said.

Authorities here said police reacted as they should have to the shooting incident, praising the initial response, which included two school police officers trying to intervene, though they have not yet provided details of the interaction that led to Pagourtzis’ surrender.

Galveston County Judge Mark Henry described the quick actions of the school police officers as “very critical.”

Santa Fe Independent School District Police Chief Walter Braun said that the police officer wounded in the shooting was in “critical but stable condition” at an area hospital. He said his officers “did what they were trained for. They went in immediately.”

Governor Abbott said Pagourtzis wanted to commit suicide, citing the suspect’s journals, but did not have the courage to do so.

Some aspects of the shooting had echoes of the massacre at Columbine High School in Colorado in 1999. The two teenaged killers in that incident wore trench coats, used shotguns and planted improvised explosives, killing 10 before committing suicide themselves.

It was the second mass shooting in Texas in less than seven months. A man armed with an assault rifle shot dead 26 people during Sunday prayers at a rural church last November.

Additional reporting by Reuters