Why is Najib pushing fake news laws before Malaysia election?

While the prime minister and his ruling Barisan Nasional coalition claim the bill is to protect citizens, observers are not convinced Najib and his lieutenants solely have the national interest in mind

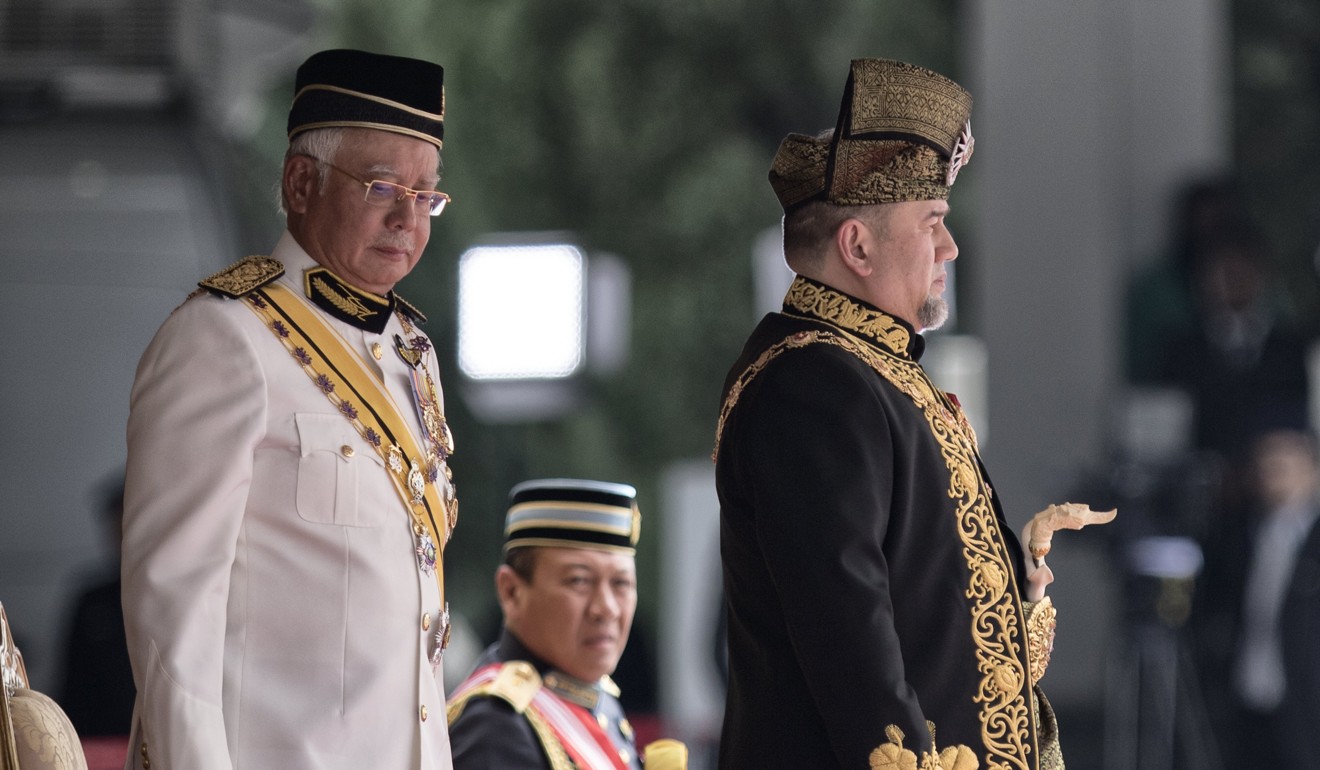

In Malaysia, where the mere act of caricaturing Prime Minister Najib Razak as a clown could get you thrown in jail, plans for a new law to stamp out “fake news” before a landmark election have set alarm bells ringing among the opposition and free speech proponents.

The government for months has been floating trial balloons about the law, and this week confirmed a bill was in the works and could be passed before the polls, which are likely to be held in April or May.

In a speech outlining the government’s legislative agenda for the current parliament session – which lasts until April 5 – the country’s King Sultan Muhammad V voiced “great support” for the law.

Malaysian election: Hong Kong billionaire Robert Kuok targeted by anti-Chinese whispers

Cabinet Minister Rahman Dahlan told Reuters after the speech that the law could have broad powers.

“Even spreading [bad] news about the economy is bad. [Fake news would be] anything that is not substantive, and dangerous to the economy and security of the nation,” said the minister, who leads strategic communications efforts for the ruling Barisan Nasional coalition.

Observers are not convinced Najib and his lieutenants solely have the national interest in mind.

In neighbouring Singapore, there is similar scepticism among the civil society about a parliamentary select committee convened by the government to look into the same issue.

Singapore and Malaysia are within touching distance in the latest Reporters Without Borders press freedom index – ranked 151 and 144 respectively.

What could go wrong for Najib when Malaysia goes to the polls?

Critics have seized on officialdom’s thin-skinned reputations. “The idea is to scare people into thinking twice before they publish negative news,” said James Chin, director of the Asia Institute at Australia’s University of Tasmania, of Kuala Lumpur’s moves.

Phil Robertson, the deputy director for Human Rights Watch in Asia, was equally cynical about the objectives of the mooted new law in Malaysia.

“In Malaysia, the government is clearly unhappy with the coverage it receives from a number of news websites which so far have defied government efforts to mute them – so I expect this law aims to intimidate them,” Robertson said.

Will insulting Robert Kuok cost Najib and Barisan Nasional the Malaysia election?

The mounting number of prosecutions against Najib’s dissenters back up such claims.

In February, a district court imposed a one-month jail term and a 30,000 ringgit (US$7,700) fine on artist Fahmi Reza for a caricature of Najib he posted on social media that depicted the premier wearing clown make-up and having deeply arched eyebrows.

The 40-year-old was found guilty of disseminating content deemed “obscene, indecent, false, menacing, or offensive in character with intent to annoy, abuse, threaten or harass another person”.

The country’s handful of independent online news outlets have also been the subject of a crackdown.

Najib has maintained his innocence since the scale of corruption was made public in 2015.

The prime minister also has a civil suit pending against the same portal over readers’ comments he claimed were defamatory.

Can Malaysia, Singapore be trusted to debunk fake news?

Barisan Nasional head honchos in the past have dismissed criticism that its measures to curb fake news have an insidious intent.

They say the launch last March of the Sebenarnya (‘In actual fact’) portal, a state-run fact-checking website, shows the government is sincere about wanting to deal with the scourge of fake news.

Wong Chin Huat, a researcher at Malaysia’s opposition-backed Penang Institute, said “many people are very sceptical of such mechanisms”.

“For example, would it acknowledge damaging news regarding 1MDB or simply dismiss them as fake news?,” he added.

So is there a way for dissenting Malaysians and Singaporeans to forestall the impending measures?

Human rights defender Robertson said “now is the time” for the civil society in both countries to “make noise, demand hearings, use social media and press the political opposition to stand up”.

In Philippines and Singapore, one man’s fake news is another man’s free speech

“Make sure that the government knows they can’t attack sources of news as “fake news” because such a determination is inherently subjective,” the Bangkok-based activist said.

Philip Bowring, a veteran Asia-based journalist and a former editor of the Far Eastern Economic Review, said the mainstream media had a major part in fighting the fake news scourge.

One reason for the proliferation of fake news was traditional news outlets’ “ill-advised attempts to ape social media’s approach to news, and generally trivialise coverage”, he said. ■