‘The Chinese are coming’: in Indonesia, education doesn’t stop people believing falsehoods

- Popular discourse is being held hostage to three major untruths – fear of Chinese migrants and communism, as well as perceived attacks on Islam and its scholars

- And a good education provides little protection against the mighty power of misinformation, a new study has found

Hoaxes and misinformation have been widely blamed for Indonesia’s violent unrest this year in the wake of its presidential elections. Indonesian politicians made reference to a “fire hose of falsehoods” in explaining the riots that broke out in September.

Three scare stories in particular among six presented to Indonesians in nine provinces as part of a recent study were found to be consistently widespread.

The perceived resurgence of the Communist Party of Indonesia, otherwise known simply as PKI, was regularly cited by respondents, as well as a belief that there are millions of Chinese labourers in the country. Others consistently were taken in by what they saw as attempts by authorities to criminalise Indonesia’s ulama – influential Islamic scholars who act as the guardians and interpreters of religious knowledge.

The Religious Freedom Survey was carried out by the Indonesian Institute of Sciences, in Aceh,

North Sumatra, Banten, Jakarta, West Java, Central Java, Yogyakarta, East Java, and South Sulawesi.

These provinces were of special interest since several previous studies have identified the regions as hotspots of religious intolerance. They are also home to a combined total of 130.2 million registered voters – just over 68 per cent of the nation’s electorate.

Three other major hoaxes or pieces of misinformation were also put to the survey respondents, to gauge whether they were familiar with the six theories and how much they believed in them. They were asked about the belief among some Indonesians that there had been attempted attacks on ulama by deranged people. Another hoax put to them was the flat Earth theory, along with misinformation stating that millions of Indonesian Muslims were being converted to Christianity. The flat Earth theory was the only one that did not have any bearing on the legitimacy of the government.

Beijing the bogeyman: how fake news fuels fears in Malaysia and Indonesia

THE CHINESE ARE COMING, ALLEGEDLY

Misinformation about Chinese foreign labourers was exceptionally high in Banten and South Sulawesi. Why? Local context plays a big part. People in both regions have an unfavourable perception of the Chinese as an ethnic group, according to past studies. Particularly in South Sulawesi, familiarity with such misinformation is much higher than with any other issue. In addition, Banten and Morowali in Central Sulawesi have visibly high concentrations of Chinese labourers.

In Jakarta, Banten, West Java, East Java, and South Sulawesi, the Chinese labourers belief was the most

widespread among the six. More than 50 per cent of respondents had heard such ideas passed around. Meanwhile in Aceh, North Sumatra, Central Java and Yogyakarta, ideas about a PKI resurgence were most commonly found. Criminalisation of the ulama was less discussed but was still widely known – in Jakarta, Banten, and West Java, more than half of respondents were familiar with the idea.

Indonesia’s election riots offer a lesson on the perils of fake news

Indonesian President Joko Widodo has on several occasions felt the need to officially dismiss these rumours after they were widely circulated on social media and instant messaging apps such as WhatsApp. In August last year, Jokowi, as the president is popularly known, provided clarification on the actual number of Chinese foreign workers in Indonesia during a speech to members of the Indonesian Ulema Council. In a meeting with the traditionalist Sunni Islam movement Nahdlatul Ulama, Jokowi also denied accusations about criminalisation of the ulama.

Influential political figures have played an active part in spreading rumours. Ideas about the resurgence of the PKI as a threat to the nation were prominent at the height of the New Order regime between the 1960s and 1990s under dictator Suharto. Their prominence in today’s Indonesia cannot be separated from the way figures such as Gatot Nurmantyo, former commander of the Indonesian National Armed Forces, have raised the issues in the media. Amien Rais, a senior politician from the National Mandate Party, has accused the government of supporting the resurgence of the PKI.

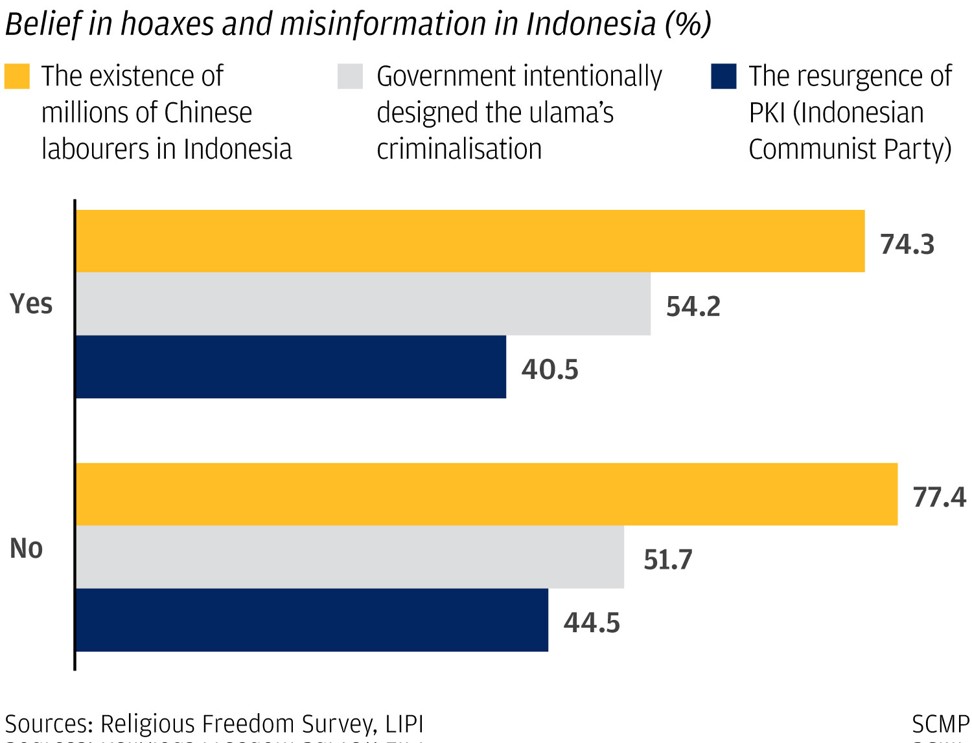

In every region surveyed, more than 60 per cent of those familiar with misinformation about Chinese labourers believed it to be true. In Aceh, North Sumatra and South Sulawesi, the figure was more than 80 per cent. While ideas about the resurgence of the PKI were well known, the number who believed them never reached beyond 53 per cent in any of the nine provinces. Figures for belief in ulama criminalisation were always somewhere between the two other theories. The popularity of misinformation about Chinese labourers challenges a commonly held perception in Indonesia that the spread of disinformation has mainly been driven by religious sentiment.

In Malaysia, fake news of Chinese nationals getting citizenship stokes racial tensions

LEARNING FALSEHOODS?

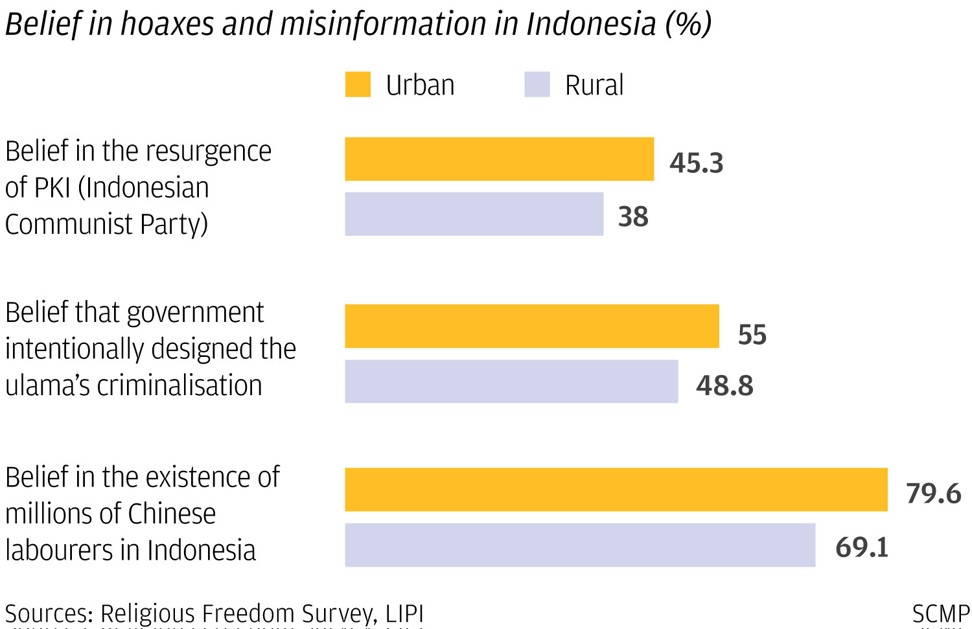

Education is often assumed to be the antidote for the spread of hoaxes and misinformation. Yet the data showed that higher education does not necessarily make Indonesians more capable of spotting fake news. The better educated know more, but do not necessarily have the ability to distinguish the validity of that knowledge. Those with higher education are in fact at greater risk of believing in more falsehoods than those with lower educational backgrounds. Since the better educated often live in urban areas, city dwellers were therefore also no less likely to believe in untruths. Neither did the availability of the internet endow survey respondents with better skills for ascertaining the truth.

Hoaxes and misinformation pose a clear and present threat to Indonesian democracy. The role of well-informed people in shaping and maintaining a healthy democracy is vital. It will be important to incorporate critical thinking and digital literacy into the educational curriculum to develop the ability of Indonesians to better distinguish truth.

Ibnu Nadzir is a researcher with the Centre for Society and Culture at the Indonesian Institute of Sciences. Sari Seftiani is a researcher at the institute’s Centre for Population Studies, and Yogi Setya Permana is a researcher at its Centre for Political Studies. This article is an edited excerpt from a paper titled “Hoax and Misinformation in Indonesia: Insights from a Nationwide Survey”, published in ISEAS Perspective No 92 by the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore