Critics slam Duterte’s move to axe franchise of Philippine broadcaster ABS-CBN

- In a Supreme Court filing, the Duterte government accused ABS-CBN of greedy business practices and breaching ownership laws

- The case has thrown a spotlight on the use of the quo warranto petition – a legal mechanism favoured by the administration to ‘silence critics’, observers say

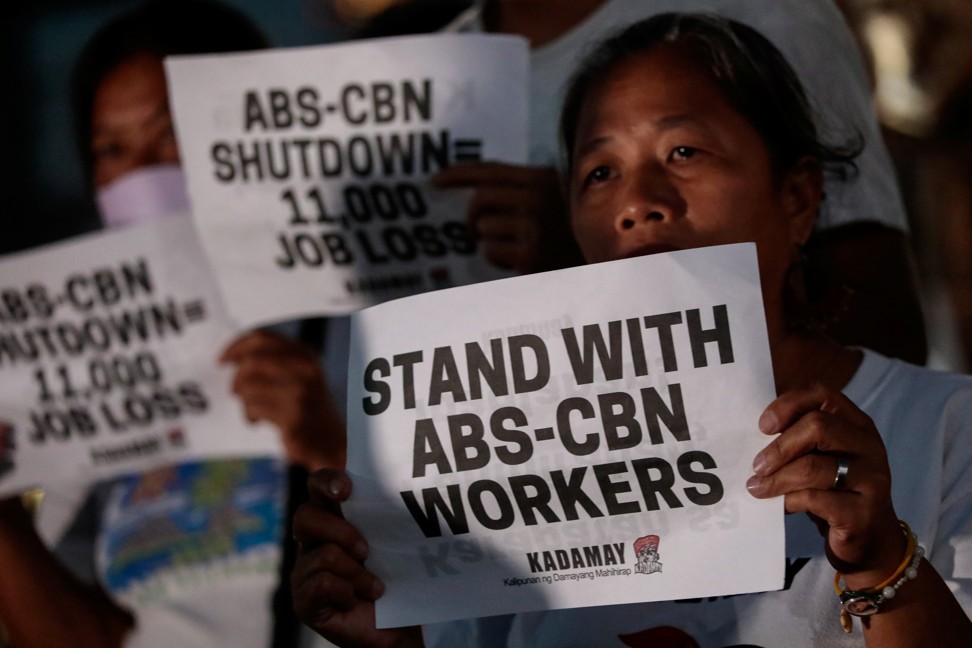

On Monday, the administration filed a petition at the Supreme Court, accusing the network of violating ownership laws and of “highly abusive practices” such as charging viewership fees.

The official who filed the case, solicitor-general Jose Calida, said in a statement that the authorities wanted “to put an end to what we discovered to be highly abusive practices of ABS-CBN benefiting a greedy few at the expense of millions of its loyal subscribers”.

But according to critics, the issue is both personal and political. The president has openly harboured a grudge against the broadcaster: three years ago, Duterte said he was furious because he had paid for several TV ad spots on ABS-CBN during the 2016 presidential campaign, but the network did not air them. Accusing the station of “swindling”, he also slammed it for running news stories about his alleged secret bank accounts.

Duterte said then he would block the renewal of ABS-CBN’s franchise, which expires this March.

“I will not let it pass,” he said in 2018. “Your franchise will end. You know why? Because you are thieves.”

Putting the company out of business would appear to not only avenge the slight, but also neutralise a media firm that has been critical of Duterte’s government, an observer said.

“It’s personal, he really thinks ABS-CBN was unfair,” said Vergel Santos, veteran journalist, trustee and former chair of the Centre for Media Freedom and Responsibility (CMFR).

Describing Duterte as “contemptuous of the press”, Santos added: “This is a narcissistic president; the only way of ruling he knows is by dictatorship.”

Senator Risa Hontiveros described the Supreme Court filing as “an attack on the free press and a vindictive move against critical journalism”.

Duterte’s disrespect for the press is well known, especially against news companies that have criticised his deadly war on drugs and the various corruption scandals that have befallen his administration.

In 2016, he said: “Just because you’re a journalist you are not exempted from assassination, if you’re a son of a b****.”

Legal analysts have pointed out the method used on Monday, a quo warranto petition – which questions the authority of a person or company – was made on shaky grounds.

Antonio La Viña, a law professor, called the move “preposterous and a case without legal basis”.

“The grounds are flimsy” and “quo warranto is not a proper remedy for the kinds of issues being raised”, he said in a series of tweets.

It was also an attempt to bypass an established process, La Viña said. Franchise issues are handled by government agencies and the Philippine congress, not by the Supreme Court, he said.

According to human rights lawyer Jose Diokno Jnr, “filing quo warranto to silence critics” was a tactic favoured by the Duterte government.

The method was also used in 2018 to oust a Supreme Court chief justice Duterte did not like.

Diokno described quo warranto as “a new weapon to stifle our freedoms, and [the administration is] using it against ABS-CBN now. Who’s next?”

On Monday, Duterte’s spokesperson Salvador Panelo denied the Supreme Court filing was a directive from the presidential palace, saying there was “no politics involved”.

“The solicitor-general is constitutionally bound to institute any action against any transgressors of law,” Panelo said.

If ABS-CBN loses its franchise, the company would have to stop broadcasting TV and radio programmes on its current frequency, but can continue operating on cable and online.

According to Santos, there was a possibility that in attacking the broadcaster, the president could cause its value to fall, giving his allies a favourable path into ownership.

“There is money to be made, but the point is to have a Duterte-friendly owner of a network,” he said.

ABS-CBN is no stranger to politics or controversy. The country’s largest broadcast network, it is owned by the Lopez family, a once-powerful and wealthy oligarchy who controlled the media corporation, a daily broadsheet, and the Philippines’ largest electricity company in its heyday around the 1970s. They were also actively involved in politics, with one even becoming a vice-president.

The family’s fall came when dictator Ferdinand Marcos grabbed power in 1972, and he confiscated ABS-CBN, turning it into a government propaganda studio.