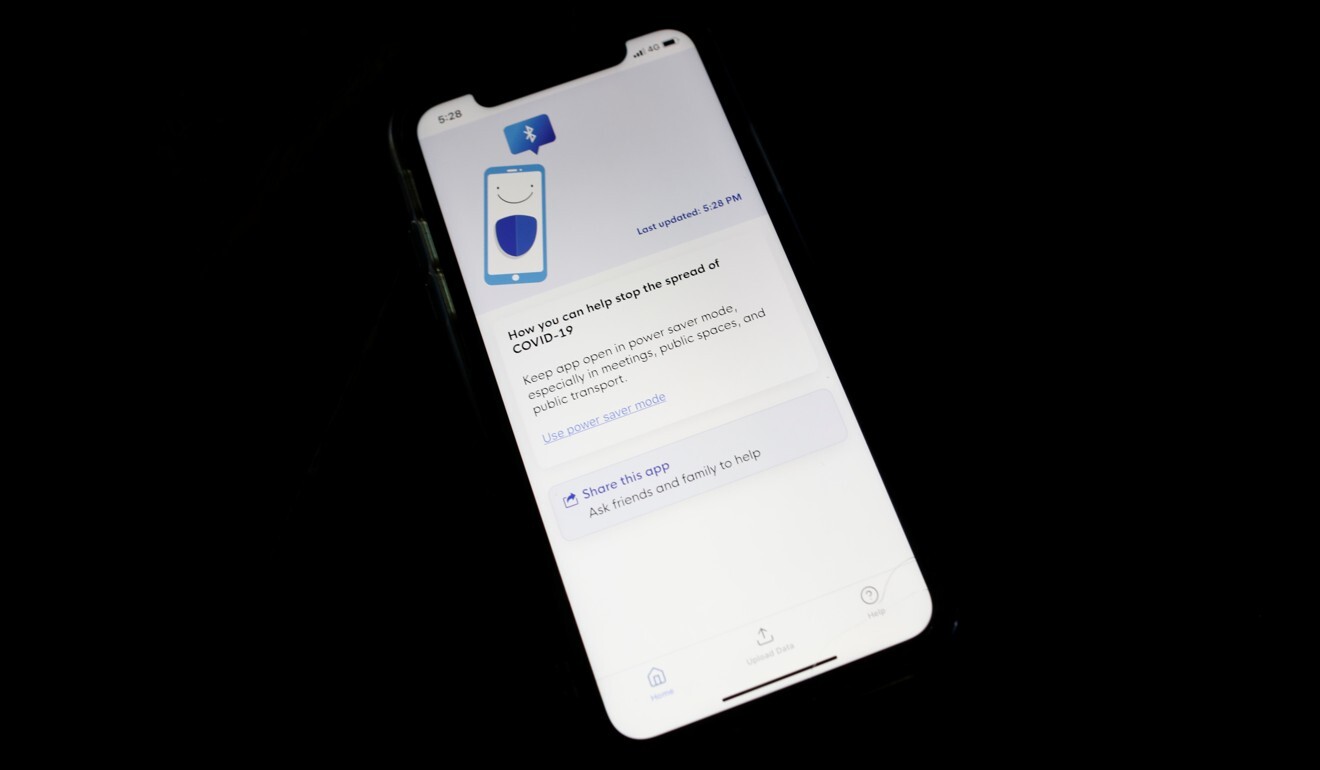

Coronavirus: why aren’t Singapore residents using the TraceTogether contact-tracing app?

- Data privacy is a concern, but the contact-tracing app’s interface is also ‘unexciting’ and a drain on one’s smartphone battery, an analyst says

- Authorities are watching the app’s uptake as they come up with measures to ease Singapore’s ‘circuit breaker’ lockdown from June

The final-year student at the National University of Singapore remains wary even though the authorities have outlined the types of data they would collect, and how this would only be used to contact those potentially infected by the Covid-19 disease.

“If I sign up for the app, I am afraid of how it could potentially reveal locations that I have visited, and what it might disclose about my movement,” he said.

Contact tracing apps: panacea, privacy invasion, or simply flawed?

About 1.4 million users have downloaded the app but National Development Minister Lawrence Wong, who co-chairs a multi-ministry task force to manage Singapore’s response to the pandemic, has said three-quarters of the population must have the app in order for it to be effective.

Authorities will take into account the adoption of the app as they prepare to roll back lockdown measures when the “circuit breaker” ends on June 1, and this has sparked discussion on whether the app should be made mandatory.

While the government initially said construction workers – the first group allowed to resume activities in June – would have to use the app, it later retracted the statement, saying it was up to employers to establish a tracking system and they could consider using Trace Together.

Singapore’s NCID sees ‘recurring waves’ of coronavirus until vaccine found

Singapore residents’ wariness towards the app is due to a combination of factors, experts said, including whether their data will be kept safe and what it will be used for.

According to a survey conducted by Singapore-based independent pollster Blackbox Research, 45 per cent of respondents did not download TraceTogether even though they had heard of it, and the main consideration was that they “did not want the government tracing their movements”.

“At the heart of this is a trust issue,” said Teo Yi-Ling, a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies’ Centre of Excellence for National Security. She noted that even though authorities had stressed how data would not be misused, people still remembered past instances of cyberattacks on government databases.

One example was in June 2018, when hackers copied the hospital records of more than 1.5 million patients, of which 160,000 had information about their outpatient dispensed medicines taken, in an incident described by authorities as the “most serious breach of personal data”.

“The concern about data security may be the thought of ‘[not wanting to] let the authorities have this data about me because I don’t know if it will be safe’,” said Teo during a panel discussion on the use of data-gathering tools by the Institute of Policy Studies on Wednesday.

She added that the idea of having a tracing application installed on one’s smartphone “hits closer to the bone in terms of feeling that your movement has been traced”, even though Singapore is known for having surveillance cameras planted across the island. The city state is the 11th most-surveilled city in the world, according to a 2019 report by UK consumer comparison website Comparitech.

Singapore has also implemented a digital check-in system called SafeEntry, where people visiting businesses have to scan their identity card, with their details stored on a government server. TraceTogether on the other hand, stores data on an individual’s phone and would be accessed only when needed.

This then boils down to transparency, and how the government needs to more clearly address how it is going to use the data, and the measures that it would take to secure them, said Teo. This comes particularly so when the personal data act in Singapore only applies to individuals and business organisations and not the government.

Coronavirus: when will Singapore’s recovery rate of 15 per cent pick up?

Even so, Christopher Gee, senior research fellow at Singapore’s Institute of Policy Studies, thought the severity of the pandemic warranted authorities making the app compulsory. Although he acknowledged that this might lead to a “slippery slope” of greater surveillance of personal data by the government, the current situation was an “immediate crisis” and that Singaporeans would “implicitly understand the idea that personal liberties and rights would have to be subordinated in the public interest”.

“Given the speed of things happening, what we do need is a law and for the government to make it mandatory, as [with] the situation with the face masks and having to wear them in public,” Gee said, adding how the city state could formulate some sort of citizen charter for digital public services.

Lawrence Loh, an associate professor of business administration at NUS, pointed to other issues with the app. He described the interface of the application as “unexciting”, adding that the need for users to turn on their Bluetooth would drain battery.

To deal with this, the authorities say they are now working with tech giants including Apple and Google to enhance the functionality of the app, and are mulling the introduction of wearable dongles to include non-smartphone users.

Others might not see the need to download the application as they are not heading out as much given the current partial lockdown in Singapore, said Teo. The city state’s so-called circuit breaker measures had earlier kicked in on April 7, with most workplaces and schools shut, and would expire only on June 1. This concern may be less relevant as Singapore focuses on gradually reopening its economy, she added.

Tests, tracing, telemedicine: Singapore tech fights virus surge

Ang Swee Hoon, an associate professor of business administration at NUS, suggested that the low take-up rate for TraceTogether could be due to a lack of marketing. She said that the fast-moving situation meant that Singaporeans had focused on the more sensational initiatives by the government.

“News has been talking about all these other measures and we only have a finite attention span … that might have taken away attention from the tracing app,” Ang said. She suggested that officials made use of advertisements on national broadsheets that were initially used to promote regular handwashing during the early days of the outbreak.

A nudge could thus improve the number of downloads as Singaporeans are “generally quite cooperative, even if they are not community-centric”, said Howard Lee, a postdoctoral student at Murdoch University’s Asia Research Centre. Lee, who carries out research on media governance, said if Singaporeans were convinced the app was absolutely necessary for the country to emerge from the pandemic, they were more likely to cooperate.

Teo also said some people may not be familiar with how to react to the government taking their data, adding that when consumers provided information to corporate entities, there was a form of transaction being made. “But in terms of the government wanting to use my data, I am not sure what I get back in return. Maybe that’s not clear yet, and maybe that’s something the government has to assure people of,” she said.

But it might ultimately be a waiting game for some Singaporeans, who said they would only download the app when the usage rate becomes more widespread or if the virus situation spirals out of control.

Zhu, the NUS student, said: “I know it’s a social responsibility to download the app, but that won’t work unless a significant proportion of the population are using it. I’m just not sure if it’s a trade-off I’m willing to take right now.”

Help us understand what you are interested in so that we can improve SCMP and provide a better experience for you. We would like to invite you to take this five-minute survey on how you engage with SCMP and the news.