In Hong Kong, China should learn from India’s healthy attitude to the British Empire

- Empire’s critics often fail to understand that imperial subjects are not passive recipients of coercion. They can make imperial structures their own

- The structures of British rule in Hong Kong – its legal system and free media – have become a way of life not as foreign intrusions, but as another way of being Chinese

Japan’s Abe skips Yasukuni Shrine visit to avoid ‘upsetting China’

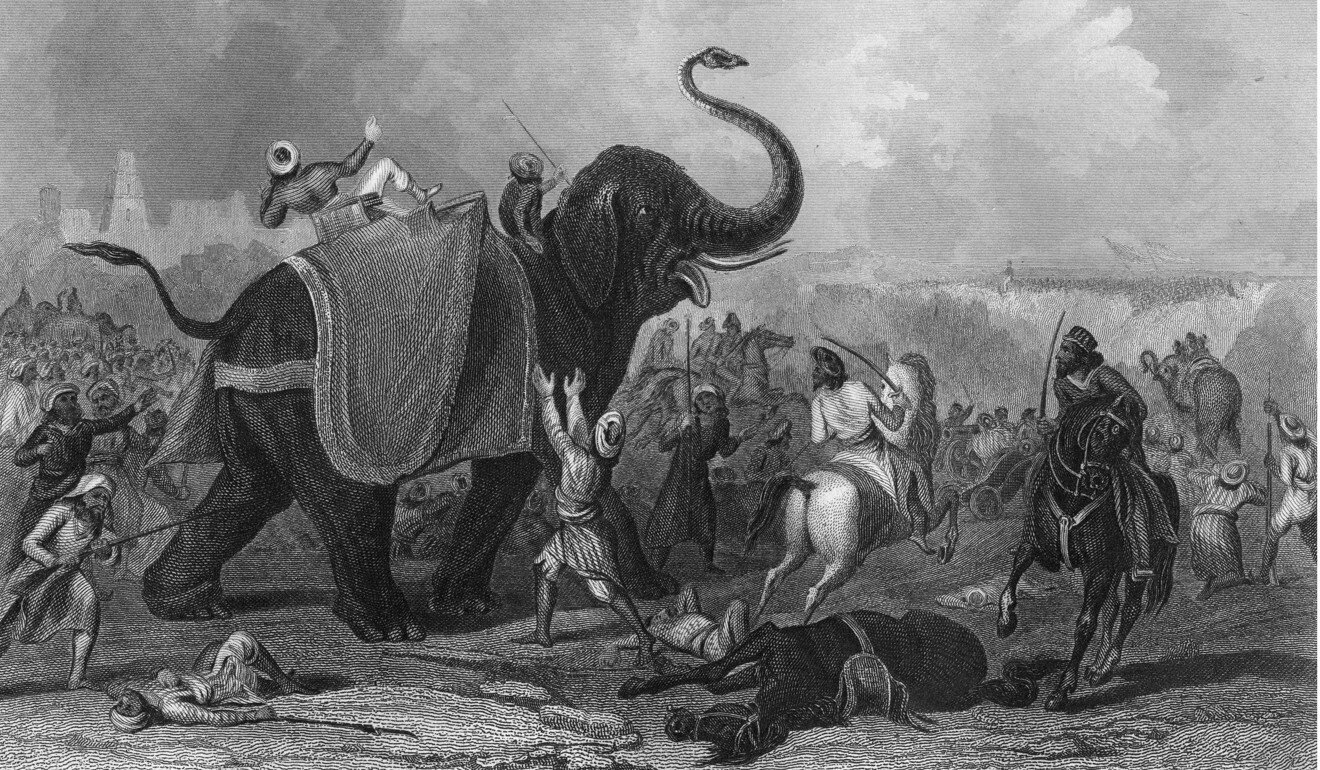

In the summer of 2020, the debate over empire in Britain has concentrated on the question of whether it was good, bad or something in between. At one level, the question doesn’t really make sense. Empires depend on coercive power; they are not republics, nation-states or democracies and by definition depend on inequality. Defenders of the British Empire argue that it brought good things in its wake, such as rule of law (as if conquered countries had no legal system of their own) or railways (as if countries that resisted conquest could not have bought or built railways). Those arguments have a flavour of the old philosophical conundrum: if you rob a bank and give the money to an orphanage, does that excuse the robbery?

Britain thinks China is the new USSR or Japan. It needs to rethink

The ethics of empire cannot be understood without understanding the nature of power. That is the first principle that needs to be understood when judging empire.

But empire’s critics often fail to understand something crucial: that imperial subjects are not passive recipients of coercion. They can change imperial structures, resist them, and make them their own.

After World War II, China valued personal freedoms. It should remember that

Yet the structures of British rule also included a robust legal system, increasingly free media, and structures such as the Independent Commission Against Corruption (a welcome colonial innovation to deal with the darker side of colonial rule). All these have become part of the structure of Hong Kong’s way of life not as foreign intrusions, but as another way of being Chinese. It makes no more sense to argue that Hong Kong’s colonial legacy is purely foreign, or irrelevant to Chinese identity, than it does to suggest that China’s constitution should be abolished because its first iteration was debated by a Manchu court in the late Qing dynasty.

Yet much of the current Chinese anger about “foreign” interference derives its intellectual firepower from arguments about “imperialism” that would not be out of place in the Chinese political language of a hundred years ago.

Yet overall, “imperialism” was never a core element of the political debate in independent India, and it isn’t now. Having fought with vigour to end British rule, the former imperial power is generally treated with a mixture of affection and disregard by India’s ruling elites.

In Hong Kong’s national security law era, echoes of Northern Ireland’s Troubles

Rana Mitter’s most recent book is China’s Good War: How World War II is Shaping a New Nationalism (2020)