Tough rhetoric at the US-China talks sets the tone for future ties: clashing as a rival, and working as a partner

- While acrimony and accusations dominated the media coverage, Beijing and Washington were able to lay down markers and understand each other’s bottom lines

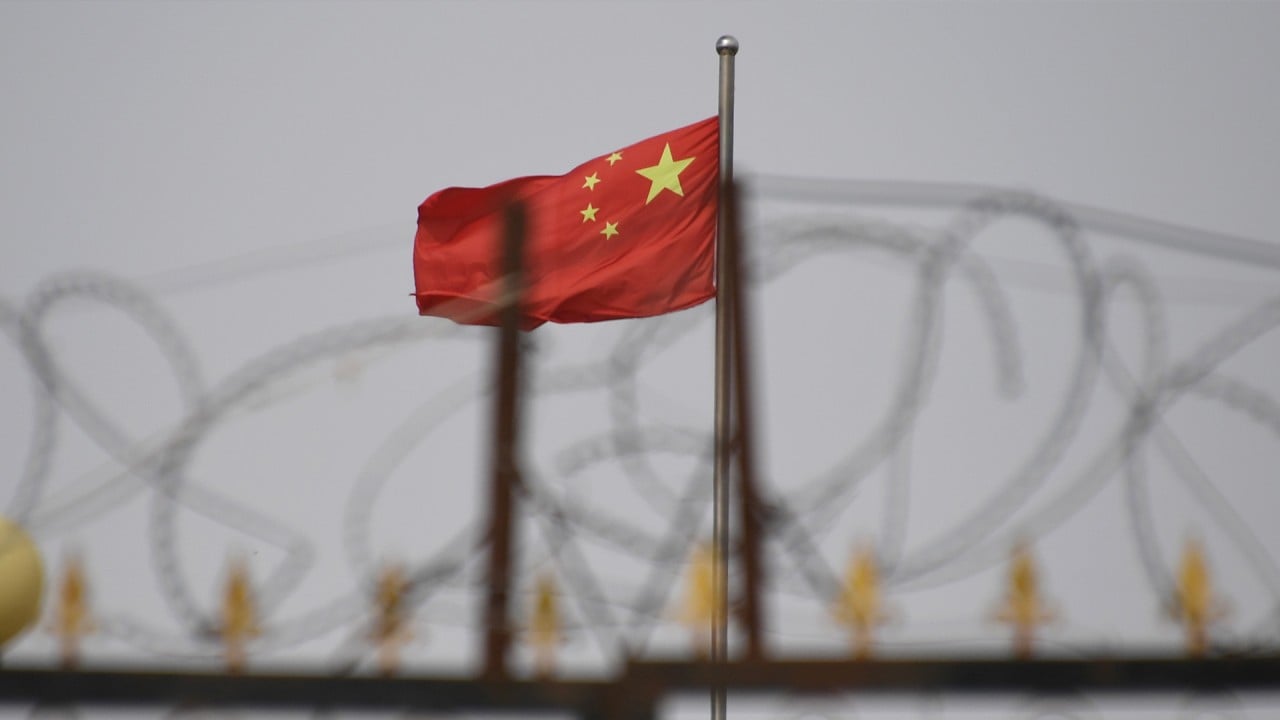

- Though sanctions related to Xinjiang followed the meeting, China’s best defence is to lay the groundwork for more foreign investment

While the fireworks may be unusual and undiplomatic for the world’s two most powerful countries – particularly as they are looking for ways to reset their fraught ties – they should hardly come as a big surprise.

In fact, what transpired has helped set the tone of their relationship, and brought more clarity to what it will be like in the future: Beijing and Washington will most likely see more intense confrontation over values and rules, but they will also seek dialogue and cooperation on other bilateral and geopolitical issues that are in their best interests.

Of course, the tricky part is how to walk the fine line between simultaneously clashing as a rival and working together as a partner.

In that sense, the two-day meeting in Alaska turned out much better than the way it was reported by international media, as both sides were able to air their grievances, lay down markers and get a better understanding of each other’s bottom lines.

Media coverage and public discussions focused on the opening remarks, which were originally scheduled for eight minutes but turned into fiery exchanges that lasted about an hour. However, the closed-door meetings that lasted many more hours and actually covered a wider range of bilateral and geopolitical issues received scant public attention.

According to Chinese state news agency Xinhua, both Beijing and Washington have expressed hopes to continue their high-level communications, and they have agreed to set up a joint working group on climate change, one of the areas for major cooperation between the two of the world’s largest polluters. On Tuesday, John Kerry, the Biden administration’s top climate official, joined a virtual meeting on climate change co-hosted by China.

Moreover, the news agency also said both sides had exchanged views on economy and trade, military, law enforcement, culture, health, cybersecurity, climate change, the Iran nuclear issue, Afghanistan, the Korean peninsula, and Myanmar. That is a long list of substantive issues, most of which would call for closer cooperation.

Given rising tensions over Taiwan, Washington’s reiteration of the one-China policy, which Beijing considers the most important red line, also helped ease concerns.

Unfortunately, however, the adversarial nature of their ties, and of China’s relations with the West in general – characterised by vitriolic rhetoric and tit-for-tat sanctions – is expected to dominate the public discourse in the near future.

As the saying goes, foreign policy is a continuation of domestic politics. This is true for Washington and Beijing, both of which have to answer to an increasingly nationalistic audience at home.

Following that logic, the fiery exchanges between Chinese and American diplomats were not spontaneous at all – they were well calculated. And, judging from reactions, they were also mostly well received in both countries.

In China, top diplomat Yang Jiechi received high praise for publicly rebuking the US for its criticism of China’s human rights and for saying it could no longer “speak to China from a position of strength”.

Some Chinese media and commentators have hailed Yang’s performance as a historic moment that saw China finally standing up to the West after 120 years; there was even a meme trending on social media comparing Yang’s Alaska meeting with the 1901 meeting when Qing dynasty official Li Hongzhang signed an unequal treaty with invading Western powers.

The diplomat’s fiery remarks also came after Chinese President Xi Jinping earlier this month said Chinese people could finally see the world at eye level, unlike the years in which people like him were seen as “country yokels”.

Moreover, Yang’s tough rhetoric was not only aimed at the US, but also its Western allies, in anticipation of their concerted efforts to counter China – which happened just days after the Alaska meeting.

On Thursday, China also announced it had sanctioned four British entities and nine individuals including MPs and lawyers.

The Biden administration has long argued that coordinated efforts by a broad coalition of like-minded Western powers would work better in scale and strength to counter China’s rise and press Beijing to improve its human rights record.

Understandably, concerns are rising that the worsening tensions between China and the EU could jeopardise the landmark investment treaty both sides agreed to in December, with a few members of the European Parliament already saying they would not ratify the treaty when it is scheduled to be voted on in early 2022.

The treaty, seven years in the making, allows European companies unprecedented access to the Chinese market. Last year, China overtook the US as the EU’s biggest trading partner, with trade volume in goods reaching US$710 billion.

It remains a big question whether the EU would like to see such a scale of investment and trade destroyed over Xinjiang.

But as the political game of sanctions and counter-sanctions has heated up and stoked nationalistic sentiment in China, Beijing does need to fight the inclination to drag China-based foreign companies into the political wrangling.

Over the past few days, Chinese state media has started a campaign to name and shame retail giants Nike and H&M for refusing to use cotton sourced from Xinjiang and expressing concerns about forced labour in the region.

Calls for boycotting those brands and other clothing companies, including Burberry and Adidas, are trending on Chinese social media – with e-commerce platforms already dropping H&M and celebrities putting out statements to cut ties with those firms.

This follows the long-standing practice in which the official media would publicly call out foreign brands that were seen as violating China’s official positions on sensitive issues, including Tibet and Taiwan. Those foreign brands usually caved to media pressure by apologising and conforming to China’s demands, so as to maintain their access to the Chinese market.

But the practice of public naming and shaming should be used sparingly, as it could adversely affect China’s ability to attract foreign investment and create misconceptions about such investment being unwelcome in the country. There are better and more subtle ways to nudge those multinationals into toeing the line without making them the target of public anger and politicising their operating environment. In fact, Beijing should adopt an accommodating attitude towards those companies caught up in the storm, not least because they are big employers on the mainland.

This is particularly true at a time Beijing aims to use the policy of opening up to foreign investment and trade as a key tool to counter the Western governments’ actions to contain China’s rise. The more closely intertwined the Chinese economy and foreign investment have become, the more capable China will be at withstanding external shocks.

Wang Xiangwei is a former editor-in-chief of the South China Morning Post. He is now based in Beijing as editorial adviser to the paper