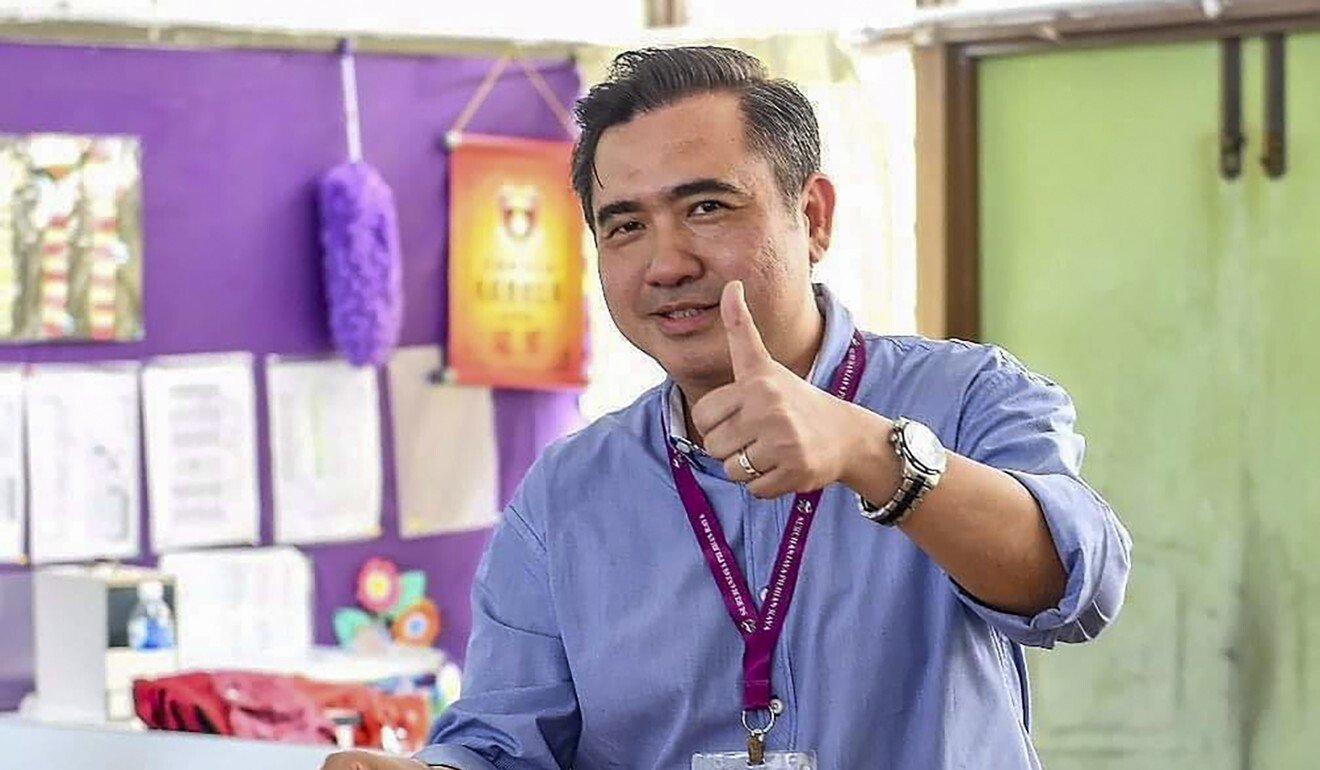

How Anthony Loke’s family restaurant honed his political skills – and spawned a Lunar New Year custom in Malaysia

- Loke is tipped to become the next chief of DAP, Malaysia’s biggest opposition party

- He credits his people skills to his time helping out at his family’s restaurant – which sold yee sang, a festive dish he says was popularised by his Chinese grandfather

When he was 10, former Malaysian transport minister Anthony Loke Siew Fook worked at his father’s Chinese restaurant with his elder siblings after school and during the weekends.

His family spent most of their time at the Hong Seng restaurant in Seremban city, Negeri Sembilan state, where they cooked, served food or prepared meals for the next day.

“I served food to the customers, took orders and washed dishes after school hours and during weekends,” Anthony said. The eatery opened at 8am for breakfast and closed at 11pm after serving supper to the crowds from the cinema next door.

The 44-year-old is a member of the Democratic Action Party (DAP), Malaysia’s largest opposition party with 42 MPs in the 222-seat parliament.

He is touted to become the DAP’s next chief in its central executive committee election on June 20.

If elected as secretary general, Anthony will helm the Chinese-dominated party at a critical moment for both Malaysia and the party, amid political uncertainties and a pandemic that has crippled the economy.

Anthony, who is now the organising secretary of the DAP, credits his experience serving food and dealing with customers as a training ground for talking to people from all walks of life when he entered politics years later.

“Serving customers trained me to talk to strangers with ease,” said Anthony, adding proudly that he also learned how to make wonton noodles and fried rice while working at the restaurant.

“When I started to get involved in politics, I did not encounter any problems dealing with grass roots and ordinary folks.”

FAMILY ROOTS

Apart from helping to hone his people skills, Anthony said the Loke family’s food business has a special connection to a facet of Malaysian-Chinese culture that has become synonymous with the Lunar New Year.

Yee sang, or yu sheng, a salad of raw fish and fresh vegetables with sweet, tangy dressing that is consumed at the annual Chinese festival, was popularised in Malaysia some eight decades ago by Loke Ching Fatt, a Chinese immigrant from Guangzhou – and Loke’s grandfather.

At the start of the 20th century, Guangzhou was home to China’s nationalist leader Sun Yat Sen and his base of operations to overthrow the Manchu dynasty and establish a Chinese republic.

Amid the revolution and wars, there was great hardship, prompting Ching Fatt to leave Nanhai county in the 1920s for Malaysia, where he finally settled in Seremban and had six children, three boys and three girls.

“Life was very hard in China at that time,” said Chee Chow, Anthony’s 82-year-old father. “Many people left. My father was part of the wave of immigrants that left the country for different parts of the world.”

Life remained difficult during World War II, but Ching Fatt persevered and opened a catering business in 1947.

Back then, there were no restaurants and most people celebrated weddings and other special occasions at home, or by taking tables and chairs out into the street. Ching Fatt often supplied the food at these events with help from his wife and children.

“We would prepare all the dishes in our house and bring it over to the homes of people having wedding banquets,” Chee Chow said.

Around the 1940s, Ching Fatt introduced yee sang to his menu – which became a hit with the Chinese community, Chee Chow said.

As the dish grew in popularity, so did the number of customers visiting the Loke family home, where queues formed and stretched out into the street.

“We started out with a few tables and chairs inside the house and also out on the streets,” said Chee Chow.

The recipe was passed down to Chee Chow, who opened his own restaurant in 1974.

Anthony said his parents shut the eatery in 1990 so as not to disrupt their children’s education. “They did not want the operations to affect my studies when I started my secondary level. Ours is a family business where my elder siblings and I helped out at the restaurant,” he said.

According to Chee Chow, his father’s original yee sang recipe contained 20 to 30 ingredients, including freshwater fish, fresh vegetables, pomelo, pickled papaya, Chinese cucumber and ginger.

“The pickled vegetables are prepared two or three months before Lunar New Year,” he said, adding that different ingredients were added to the dish over the years.

The salad is mixed by tossing the ingredients using chopsticks in a ritual known as lo hei or lo sang – the prosperity toss.

The lo hei invokes much excitement and often ends up being a rowdy affair. It is performed standing up as families and their guests toss the salad and shout out their wishes for the year ahead. The higher you toss the ingredients, the better your luck for the coming year, even if large portions end up on the floor.

In January last year, Anthony said he had the “privilege” to toss yee sang with the Grand Ruler of the Negeri Sembilan state, Tuanku Muhriz Tuanku Munawir, and his family.

“Tuanku came to know the story of my late grandfather, who pioneered the yee sang culture in Seremban in the 1940s,” the politician wrote on Facebook last year. “I tried my best to explain to Tuanku about the significance and symbolism of the yee sang dish, truly a Malaysian-Chinese culture.”

Long after the family’s restaurant has shut, the dish continues to be served in homes, restaurants and hotels across Malaysia.

“I am always proud of the fact that my grandfather started this very localised cultural tradition,” Anthony said. “Lo sang is popular only in Malaysia and Singapore … not in Hong Kong or China.”

The dish remains a constant in the Loke household.

“I still make yee sang,” Chee Chow said. “But only for the family during Lunar New Year.”