It’s exploitation, it’s abuse – but when will online sexual violence against women and children be taken seriously?

- Platforms such as social media and chat apps have allowed thousands of abusive images of minors and non-consensual content involving women to be shared

- A wider conversation about consent needs to take place, while tech companies must be held to account and law enforcement officers should receive further training

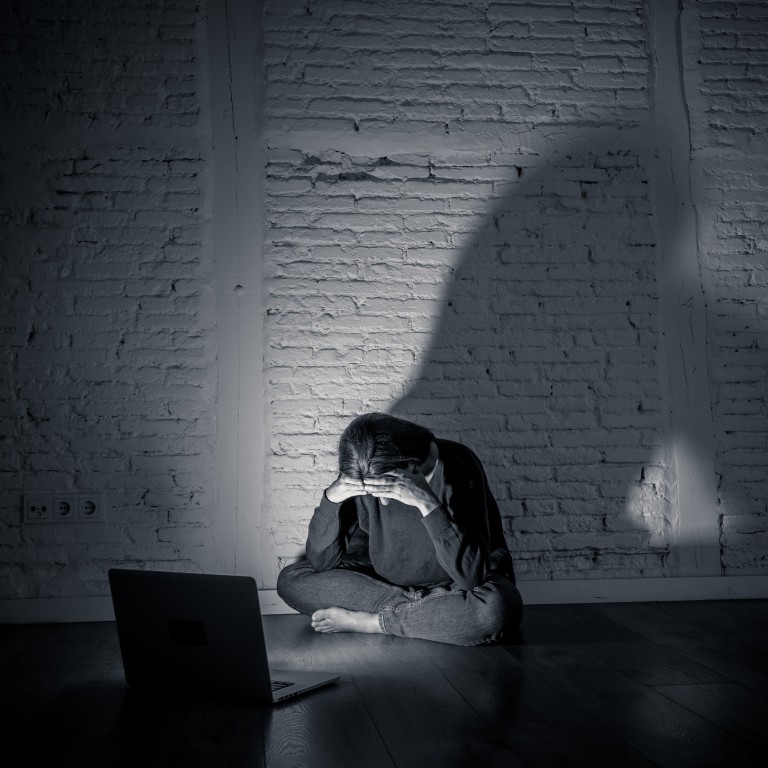

Then it got even worse. Her colleague, who had been courting her, tried to coerce her into having sex with him and threatened to share the video with her partner and work groups.

We are not talking about pornography that features adult performers who chose to be there – the issue here is about lack of consent.

I have also monitored Telegram groups that share content of women without seeking their permission, as well as abusive imagery of children.

Posts in one of the chat rooms included entire galleries of explicit images and videos involving young boys and girls, some of them engaging in sexual acts with adults.

Many Telegram channels also share – without consent – nude pictures of women; home-made sex videos; photos of women in their gym attire; and even their contact numbers and social media handles.

As I browsed through these groups, I often stared at such images, thinking that they could be of someone I knew.

Telegram seems to be actively preventing users from accessing some of the channels sharing explicit content, but only through iPhones, because – as digital rights activist Silvia Semenzin points out – they “do not want to be removed from the app stores”.

She argues that “we are putting too much power in the hands of private platforms, which can arbitrarily decide what should remain online and what is deemed offensive or dangerous”.

Telegram should make a greater effort to stop the spread of non-consensual content involving women and exploitative imagery of children across all platforms, not just on iPhones due to business reasons.

While it’s fair to say that some companies have given increased attention to this issue, image-based abuse is still not a priority. Online platforms need to invest more in technology and teams monitoring such content. They must be more proactive and responsive to survivors.

“They can’t just turn a blind eye in these situations … you make something that is broken, you pay for it to be fixed,” said Honza Červenka, a lawyer who focuses on discrimination and abuse cases in Britain and the United States.

He said there should be greater transparency and more effective ways of sharing information about those who misuse online platforms, noting that some of them did not provide enough assistance to the authorities.

Laws also need to be updated and punishments in some cases need to be heavier, while the police should put more resources into investigations as well as training for how to handle survivors’ cases in a more sensitive way.

In South Korea, sex crime prosecutions involving illegal filming increased from 4 per cent in 2008 to 20 per cent in 2017, according to a Human Rights Watch report published on Tuesday.

In 2019, the report said, prosecutors dropped 43.5 per cent of sexual digital crimes cases, compared with 27.7 per cent of homicide cases and 19 per cent of robbery cases. Meanwhile, judges often impose low sentences – last year, 79 per cent of those convicted of capturing intimate images without consent received a suspended sentence, a fine, or a combination of the two, while 52 per cent received only a suspended sentence.

At the same time, education and awareness are essential. Through inaction, many of us who use the internet have become complicit in this growing issue.

Parents need to talk about online safety and sex education with their children, not only for their protection but also to prevent them from harming others. There also needs to be a wider conversation about consent both at home, in schools, and in the media.

As Nicole Jo Pereira, an advocate from Malaysia, puts it: “No one, be it man, woman or child, should ever be made to feel as though they have lost all ownership and dignity over something so private and personal as their own bodies.”