If China weaponises capital, it will shoot itself in the foot

- British opposition to a takeover of the Welsh microchip factory Newport Wafer Fab by the Chinese-backed company Nexperia shows need for consistent, long-term strategy

- If Britain blocks off all Chinese deals on the grounds of national security its economy will take a hit; if China responds in anger it will damage its own long-term interests

The word maodun, or contradiction, has a long history in Chinese Marxist thought, but its origins go back long before communism. It refers to the “contradiction” between a spear that penetrates anything, and a shield that can never be pierced: irresistible force meets immovable object.

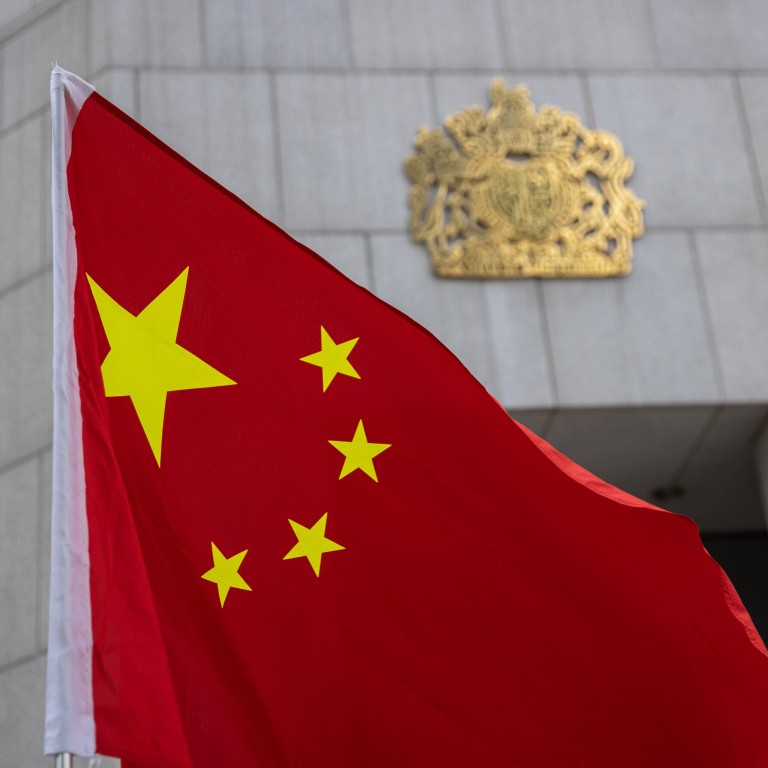

I was reminded of that fable last week during the attempted purchase of a failing chip factory (computer, not potato) in Wales by a Chinese-backed company, Nexperia.

Supporters of the deal point out that the factory – Newport Wafer Fab – does not make the most sophisticated type of chips and that the factory is only being taken over because none of its previous owners could get it to make money.

Both countries are pursuing paths that may well lead to the kind of contradictory outcomes that the original “sword/shield” metaphor captures graphically.

Britain, like many other midsized open economies, has become highly dependent on mobile international capital, as well as the development of export markets for its services and goods.

The London Sunday Times reported in May this year that Chinese investors hold around £135 billion (US$187 billion) of assets in Britain.

This might seem to give the upper hand to China. And as a much larger economy than Britain, China may point out that it can thrust its economic sword through any seemingly solid Western national security shield.

But this argument may backfire in the longer term. After all, the Chinese capital that is fuelling the British economy isn’t being given as a gift. Chinese firms don’t invest in any firm that doesn’t bring either a financial return, or have some wider relevance to national goals (as with semiconductors). Refusing to invest for political reasons in potentially profitable markets is not a winning strategy.

Then, China hasn’t solved its basic problem as a global trading actor: it wants a presence in liberal economies and societies but can’t find a productive dialogue with their public spheres.

But that kind of messaging has little resonance in societies with a more open debate about the significance of Chinese capital. Beijing frequently attests that it doesn’t like being told what to do; it should not be surprised that other countries will react similarly.

Britain needs to be realistic about whether its national shield has to be entirely impenetrable by Chinese investment. But if China continues to present its pools of capital as a sword, it will do itself long-term damage in markets where it could have thrived.

Rana Mitter is Professor of the History and Politics of Modern China at the University of Oxford and author of A Bitter Revolution: China’s Struggle with the Modern World and China’s War with Japan, 1937-45: The Struggle for Survival