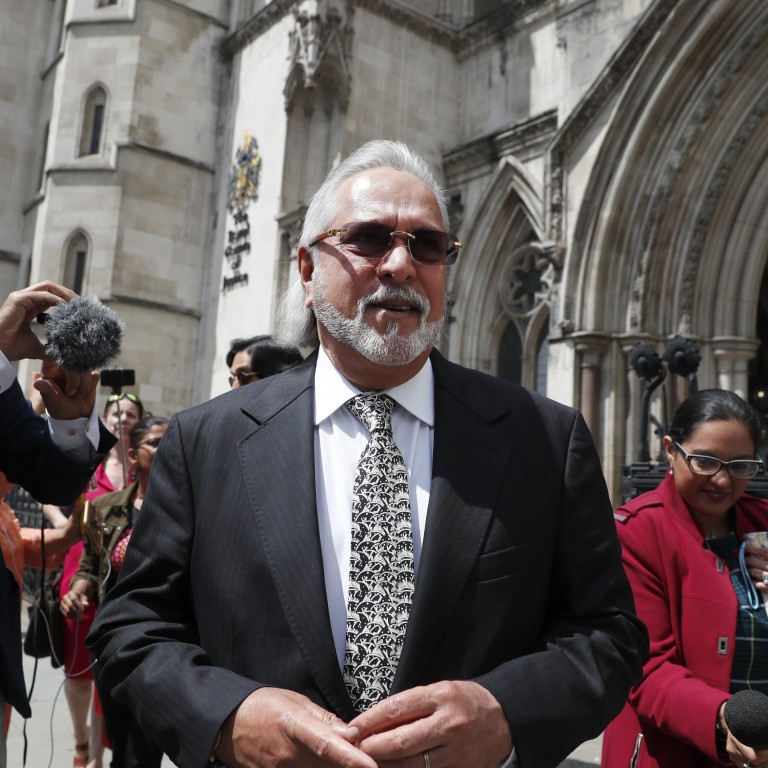

‘King of Good Times’ Vijay Mallya’s bankruptcy casts spotlight on India’s billionaires who’ve gone broke

- Mallya is the latest in a series of super-rich Indian businessmen to fail, including Anil Ambani, Pramod Mittal, Naresh Goyal and Venugopal Dhoot

- Analysts say his bankruptcy case shows the extent to which the government is now going after them to mitigate public anger over absconding tycoons

Once known as the “King of Good Times” due to his flamboyant lifestyle replete with fast cars and wild parties, Mallya’s initial success came with United Breweries Group, which owns the popular Kingfisher beer. He launched Kingfisher Airlines in 2005, but it closed in 2012 as it battled financial mismanagement and mounting debt, in part due to skyrocketing fuel prices.

Over 3,000 employees were let go and the salaries owed to them – together with arrears, now amount to about Rs 500 crore (US$67 million) and are still unpaid – leaving many in financial distress.

How India’s fugitive billionaires try to escape justice at home by fleeing abroad

The British court order now allows for Indian lenders, including the State Bank of India, to freeze Mallya’s assets globally or seek repayment of debt owed by Kingfisher Airlines, and senior Indian officials say they are looking to get the businessman extradited back to India to face the music.

Mallya is one of several high-profile wealthy businessmen whose empires have fallen, with Mumbai-based corporate lawyer Deepak Ghai saying there was also more pressure on the ruling establishment to “crack down on economic offenders, especially absconding billionaires, to mitigate public anger”.

Ghai said business founders whose good fortunes were fuelled by debt in their initial years of starting up often felt pressured to “keep up the facade of success even when things are actually falling apart behind the scenes”.

“This often leads them to make fatal mistakes leading to ugly consequences,” he said.

The chairman of Reliance Group – which has stakes in energy, petrochemicals, natural gas, retail, telecommunications, mass media and textiles – was nearly thrown in jail when he was unable to pay Ericsson’s India unit about US$77 million of past dues despite a personal guarantee. However, big brother Mukesh stepped in to settle the debt.

Pramod Mittal, 64, the younger brother of UK-based steel magnate Lakshmi Mittal – also one of the world’s richest men – was declared the “most bankrupt man” by the London High Court in 2020 for reportedly owing US$3.5 billion to debtors.

The former chairman of Ispat Industries Limited, which had investments in iron, steel, mining, energy and infrastructure, was once counted among the richest people in the UK. His daughter Srishti’s 2013 wedding to Dutch-born investment banker Gulraj Behl reportedly cost US$82 million.

Mukesh Ambani sparks succession talk as third child joins Reliance

However, Mittal’s fortunes changed when he acted as a guarantor for his company’s debts, which amounted to US$166 million in 2013. He was unable to pay and was arrested the same year on charges of fraud while also facing a money-laundering probe in India for defaulting on a US$300 million loan to the State Trading Corporation. The case was later dropped after the billionaire settled the dues of the public sector enterprise.

Goyal stepped down as chairman of Jet Airways India in March 2020 under pressure from trustees who took over the company.

Once declared by Forbes as India’s 16th richest man with a net worth of US$1.9 billion, he cut a sorry figure as he pleaded bankruptcy when the court asked him to pay US$2.5 billion owed to banks, employees and vendors.

Corporate lawyer Ghai said a common reason for tycoons’ financial woes was greed and ambition. “Many times successful businessmen also happen to be first generation tycoons who don’t have much business experience to begin with but are able to amass huge wealth due to their smart ways. Having tasted success, they develop an air of invincibility and a big ego which later trips them up badly,” he said.

This is what happened with Venugopal Dhoot, 69, who built India’s first home-grown consumer durables company, Videocon Industries, and referred to it as “India’s first multinational”.

How India’s family-run business empires battle over their billions

Later, rapid diversification in sectors such as consumer durables, telecoms, oil exploration and electronics proved to be his undoing.

The magnate’s personal wealth, estimated to be over US$1 billion in 2015, dissipated after his empire collapsed under the weight of frenetic expansion, leading to huge loans. In 2018, Videocon was dragged to court by the State Bank of India after Dhoot defaulted on paying the bank US$7 billion.

With new firms being created each day and some of them receiving massive inflows to attain unicorn status – which means they are valued over US$1 billion – there could also be more high-profile examples of those that fail and become insolvent.

More legal forums are emerging to help creditors get justice in cases of defaults and other issues, said Meghna Mishra, an advocate and partner at Karanjawala & Co, a Delhi-based dispute resolution firm.

“Apart from regular courts, the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal and the National Company Law Tribunal, both quasi-judicial bodies, adjudicate issues relating to Indian companies in a time-bound manner leading to quicker resolutions,” she explained.