India sewer-cleaning robot aims to prevent Dalits from dying in manholes

- India has tried for three decades to prevent those from the lowest caste from dying while cleaning sewers and septic tanks

- A robotic sewer cleaner developed by four university friends could help that goal and maintain the dignity of manual labourers

Mechanical engineer Vimal Govind, 29, remembers the grisly photograph that sparked the idea for his start-up’s robotic device.

Three men in 2016 had died in a sewer in Kerala, and a newspaper that covered the tragedy ran a picture that would change his life.

“Only the face of the man was visible, the rest of his body was in the manhole; the slime glistening black inside,” said Govind, who was still in university then. “I had never realised until then that human beings do this work. We have sent machines to Mars but we could not send a machine 10 metres under the ground?”

India’s Dalits rebel against insulting baby names, from ‘garbage’ to ‘dung’

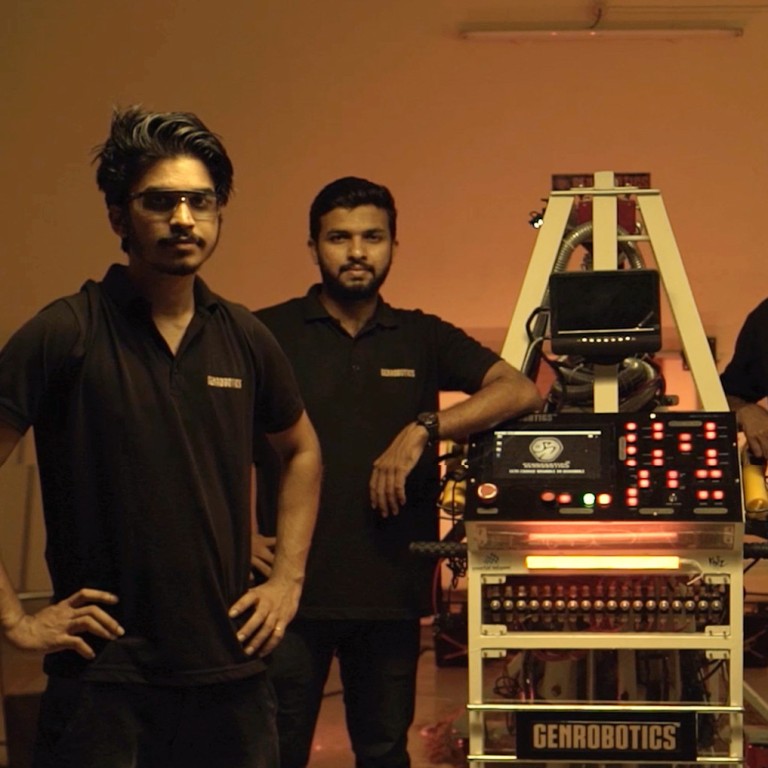

Govind is a co-founder of Genrobotics, a technology firm that seeks to eradicate manual scavenging – a job typically done by Indians from the lowest caste such as the Dalits, and one that India has tried in vain to stamp out for three decades.

The government in 1993 outlawed the manual cleaning of faecal matter and urban drainage, and in 2013 banned the employment of manual scavengers when it was clear the first law had failed to provide these workers with new livelihoods.

But still the problem persists. In April last year, Union Minister for Social Justice and Empowerment Virender Kumar said in parliament 161 people were recorded to have died while cleaning drains, sewers or septic tanks in the previous three years.

India is making another attempt to end manual scavenging, this time with technology. In the 2023 budget speech, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman said the government was seeking to fully mechanise sewage cleaning in Indian cities.

This is what Govind and his three co-founders of Genrobotics have been trying to do with their robot, dubbed the Bandicoot.

Designed by Govind and his three co-founders, the Bandicoot combines the functions of separate machines that exist on the market. The first is a suction machine, which operates similar to that of a vacuum cleaner. A jetting machine sprays water using high pressure to dislodge obstructions. Another machine, colloquially known as the bucket rickshaw, removes debris with a claw-like hand that can plunge into manholes.

The Bandicoot, which comprises a stand and a drone unit, can do all three tasks and is also equipped with cameras that help manoeuvre the robotic arm more effectively.

Govind had set up Genrobotics with his engineering college friends Nikhil NP, Arun George, and Rashid K around 2015 for social service projects. By 2017, they had graduated and moved away from Kerala. But the four could not forget about the horrific deaths of the men in the sewer near their university. In 2017, they decided to quit their jobs and move back to Kerala to work on what became the Bandicoot.

Developed with a 1 million rupee (US$12,000) grant from Kerala’s start-up mission, the first iteration of the Bandicoot was first shown and used in the state in 2017. The following year, Genrobotics’ founders showcased the Bandicoot 2.0 at a sanitation conference in New Delhi attended by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres.

The company is also a part of Modi’s “Swachh Bharat Abhiyan” (Clean India Mission) that aims to end open defecation and improve solid waste management.

“Manual scavenging is not only a death trap but also a big social stigma inside our society and the biggest living example of caste discrimination,” said co-founder Rashid K, who gave up a job as a software engineer in Mumbai to work on the Bandicoot.

Genrobotics got a boost when the Kerala government recently adopted the technology statewide, declaring that the era of manual cleaning was over.

“Now Kerala has become the first state in the country to use robotic scavengers to clean manholes,” Kerala’s Minister of Irrigation Roshi Augustine said. “The modernisation of the sewage system will help contain the spread of epidemics and serious health challenges caused by them.”

India’s ‘untouchable’ women face rejection from schemes meant to help them

Genrobotics claims the Bandicoot, which costs 3.2 million rupees (US$38,750), can clean an average of 900 manholes per day.

It says the robot is operating in a few towns in 19 states and three Union Territories, and that the start-up is also upskilling workers with technological training.

But its roll-out cannot come sooner for some workers. Tushar Jagadish Ahire, a state coordinator with Safar Karmachari Andolan (Sanitation Workers’ Union), a collective of sewage cleaners in Maharashtra state, said he had not come across the robot although the start-up had set up some machines there.

“I have never seen the Bandicoot, but I’ve seen videos of such machines to clean sewers,” Ahire said.

Safar Karmachari Andolan consists of a network of members across 21 states and one Union Territory. It works on raising awareness of the work conditions and hazards faced by manual scavengers, including by community education, helping such workers into alternative employment, and mobilising members to lobby for their concerns. In 2003, the group filed a petition in the Supreme Court arguing that a decade after manual cleaning of drains was banned, the practice continued.

Ahire said he was doubtful of the government’s plan to eradicate the problem once and for all. “If they were really serious about the commitment, wouldn’t we have seen at least an advertisement for the machine by now?”

The Indian urban affairs and housing ministry did not respond to queries about any potential purchase of machines such as the Bandicoot.

How South Asians face caste discrimination even in Australia, US, UK

Meanwhile, prominent Indian journalist Aarefa Johari has questioned the practicality of the machine in a series of reports. “Sanitation workers say it takes 10 people to move it,” she said. “How is this practical? And it is far more expensive than the humble bucket rickshaw mechanism.”

Genrobotics is aware of the criticism. “It’s true that the first model was bulky,” Govind acknowledged. “We have made the 2.0 version lighter. But it is still heavy.”

He said the technological challenges were, however, easier to overcome than the denial by some officials that the problem exists.

“We need to keep innovating and that’s what technologists do,” he said. “The main challenge is something else. Some government officials, some municipalities completely deny manual scavenging. That deliberate blindness is the biggest problem.”