In Japan, a tiny model of Tokyo could help the city’s development

- The aim of the 1:1,000 scale replica by property developer Mori Building is to understand the capital’s history and how it can adapt for future needs

- These include creating more ‘garden cities’ within the city, adding more greenery and local cultural facilities and reducing congestion

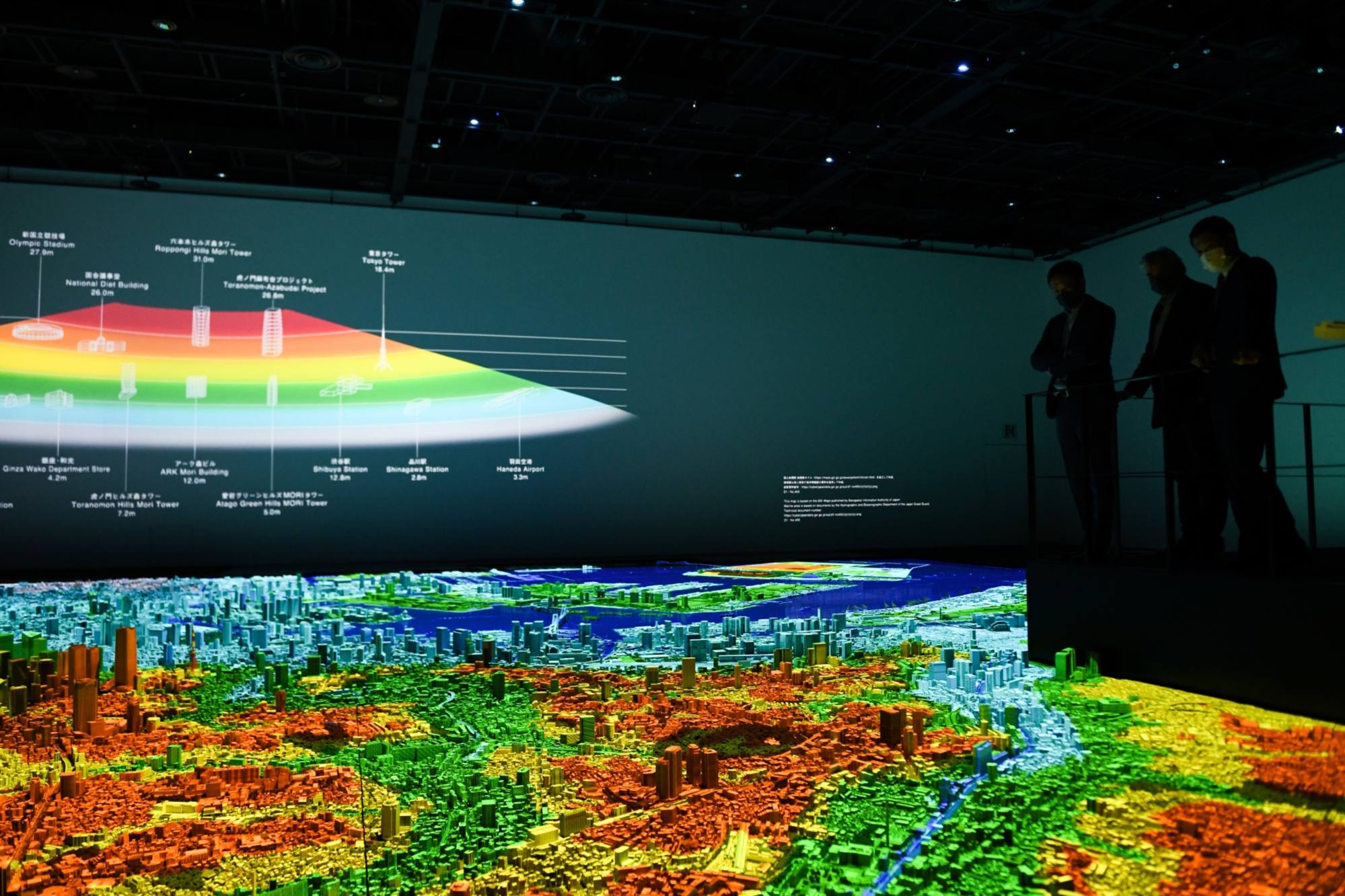

In a discreet, windowless room beneath central Tokyo lies another Japanese city. It has skyscrapers and vast bridges, port facilities and rail networks, sprawling shopping districts and narrow lanes fronted by single-storey dwellings that make up the old shitamachi districts, a hangover from the years immediately after World War II.

The Mori Building Urban Lab model includes detailed replicas of all the city’s major landmarks – the Tokyo SkyTree, the towering offices of the metropolitan government, the Imperial Palace and more – but also each individual building.

‘Extreme weather events’: Asia set for supercharged heat as El Nino looms

The model measures 24 metres by 15 metres and replicates Tokyo’s 13 central wards, depicting them in minute detail. Each tiny structure is handmade by model-makers who take photographs of each face of every building.

The images are printed out and applied to a styrofoam block in the precise shape of each building, before the blocks are placed onto a scale map of the city.

While Mori has buildings in all of the city’s 23 wards, the firm’s core interests are in the 13 areas that are the real commercial hub of the capital, with the other 10 largely being suburban sprawl with limited business development potential.

The model, not open to the public but affecting their lives nonetheless, may be time-consuming to create, but the firm maintains there is a grand reason behind it.

“Our aim is to revitalise the very heart of Tokyo,” said Masa Yamamoto, deputy manager of the company’s corporate planning department. “We want to build cities within a city, where people can live, work and relax as a community.”

The urban lab uses the latest projection mapping technology to show how the geography has changed over the centuries.

In the early Edo era (1603-1868), for example, the coast roughly followed what is today the course of the Yamanote railway line, with an inlet lapping all the way up to the outer walls of Edo castle, now the Imperial Palace.

That inlet was filled in and a series of reclamation projects have since pushed the waterfront back to its present location, more than 2km away from the palace moat.

Vanishing snow, sinking SkyTree: sobering climate change forecast for Japan

As well as the one-off model, Mori also produces the annual Global Power City Index, which ranks 48 global cities under six broad headings of economy, research and development, cultural interaction, liveability, environment and accessibility.

Tokyo placed third after London and New York in the 2022 table, but is expected to be overtaken by Paris in the next list. That makes it all the more important for Tokyo to identify its weak points – like congestion – and remedy them.

In the case of traffic flow, the model allows urban planners to identify the busiest roads and when they are jammed. This allows them to come up with solutions, like additional subway lines and stations.

Mori has been behind some significant Tokyo redevelopment projects in the past five decades, like the 1980s Ark Hills complex of offices, homes and leisure facilities, spread over 15 hectares in the heart of the city.

This concept of a “garden city” has been further developed with the Roppongi Hills megaproject, Omotesando Hills and, most recently, Azabudai Hills, its first phase completed in June. Mori also plans to obtain more land and create more garden cities.

The company says it always aims to win over local stakeholders when a new project is on the drawing board, with those people whose homes or businesses are earmarked for demolition able to get brand-new ones in the new development.

If they do not want any part of a Mori scheme, the firm buys their property from them. “We do not force residents to leave; we try to work with them,” said Yamamoto, talking of “patience” and “sharing our vision”.

He said the firm builds relationships, communicates and negotiates “as we want to build a neighbourhood that is better and greener for everyone”.

Nevertheless, it took 17 years for the company to win over landowners and residents at what is today Ark Hills – the firm’s first major redevelopment project – and 20 years to overcome concerns of locals in the Omotesando Hills shopping area.

But when people moved into modern flats with shops, restaurants and more green space and cultural facilities nearby, the resistance faded.

The firm’s vision has been broadly welcomed by city development experts, with Hiroo Ichikawa, a professor emeritus of urban planning and policy at Meiji University in Tokyo, saying garden cities “are the first time that developments of a global standard have been tried in Tokyo”.

“They are critical to the future of the city because residents and visitors need a better environment in which to live and work.”

He said that developers previously “have tended to build high rises to maximise the space, meaning there is not enough green space”.

Mori’s approach changes that “with the amount of green” combined with various facilities “making these places very different”.

Mildest winter, snow shortage in Japan as climate change worries experts

Yamamoto said the key to even better garden cities lies in knowing what people need to make life more comfortable, and elements that will attract more businesses, which is where the global city index and urban model can come in.

A dense network of railways and subway lines, along with major road arteries, can be picked out on the model, along with green space, while the Shinjuku ward stands out as the highest part of Tokyo.

That was a key consideration when the city government relocated its headquarters some years ago from the Yurakucho district – built on reclaimed land and closer to the bay – out of concern for natural disasters.

Tokyo fares relatively well among the top urban areas on Mori’s index of 48 global cities when it comes to greenery – encompassing sustainability, air quality and comfort and urban environment – with a green coverage ratio of 31 per cent.

That is second only to the 36 per cent of London, and above the 20 per cent of Paris and 10 per cent of Shanghai.

Tokyo, like most, if not all, cities, has been in a regular state of flux, devastated twice in the last century, in the 1923 earthquake and during World War II.

Elaborate plans drawn up in the aftermath of both those disasters never came to fruition, primarily as a result of the costs, but by analysing the city’s strong points and its weaknesses, Mori aims to help build a better environment for the 35.6 million people who call Tokyo home.