In Southeast Asia’s EV race, car makers gun it for the chequered flag – as consumer demand lags behind

- A recent triple-digit surge in demand for electric vehicles belies the fact that Southeast Asia lags other regions in creating viable EV ecosystems

- But EV makers are still pouring money into the likes of Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia, driven by climate change – and the US-China trade war

Malaysian human resources manager Zamir Noor, 35, thinks it’s “pretty cool” that he upgraded to an EV long before many of his friends – especially now that there’s a charging station right next door to his Kuala Lumpur gym where he can recharge his Hyundai Ioniq 6.

Southeast Asia has become a multibillion-dollar battleground for foreign investment in electric vehicles (EVs), as nations jostle for the attention of major marques: offering raw materials, tax breaks, infrastructure and tens of millions of potential future owners.

Domestic sales are multiplying fast, but are still broadly limited to the urban middle and upper middle-classes – the likes of Zamir, Sathapat and Winardy – with many mass-market buyers in Southeast Asia unable to afford entry prices that start at around US$20,000.

Instead, the big names are seeking to make their money via exports, with cheap land and labour, infrastructure and soft taxes, all appealing to companies looking to build out their supply chains.

Over the same period, EVs rose to account for more than 6 per cent of all passenger vehicle sales in the region – nearly double the figure from the previous quarter.

But the impressive numbers belie the fact that Southeast Asia still lags behind other regions where governments have already spent billions of dollars creating the necessary ecosystems to support a mass shift from conventional vehicles to EVs.

“The only challenge for me is the travel range,” Sathapat said. “If you are about to run out of battery and need to somehow go somewhere, you just can’t. It takes at least half an hour to charge.”

This lack of charging infrastructure explains why growth in the region’s EV market has been “a bit slower” than elsewhere, said Tham Siew Yean, an economist and visiting senior fellow with Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

“I think it will take a long time [for demand to pick up],” she told This Week in Asia.

But for those who can afford it, there’s never been a better time to put the internal combustion engine in your rear-view mirror, according to the early adopters.

“There is an EV car that meets most budgets now,” Zamir Noor said.

Where China leads, the world follows

The rest of the world, including Southeast Asia, accounted for just 7 per cent of total EV sales over the January-June period.

“If we look at the [total] car market, Southeast Asia comprises roughly 5 per cent of global car sales and car production,” said Putra Adhiguna, an energy specialist with the Institute of Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA). Gary Ng Cheuk-yan, a senior economist at Natixis, said Southeast Asia currently contributes about 0.65 per cent of global EV sales.

The high premium that consumers in the region have to pay to shift away from petrol cars means that demand – up until recently – had lagged behind elsewhere, Putra said.

The current forecast really looks at a slower uptake of EVs [in Southeast Asia] given the price range of the cars on the road

“So the current forecast really looks at a slower uptake of EVs given the price range of the cars on the road is quite different compared to other regions like the US and EU,” he said.

However, Southeast Asia’s growing population of more than 680 million people and burgeoning middle class do present opportunities.

As with any industry, experts say the EV market can only thrive if there is space for it to grow at scale – which means consumers need to be given good reasons to make the switch sooner rather than later.

“Yes, they are generally more expensive than the equivalent petrol car – but they make up for it in lower running cost and the quietness,” said early EV adopter Winardy, who works as a manager at a textiles firm in Bandung. “Some owners are enticed by the ‘green’ aspect, but this is more of a secondary factor.”

Local, or at least regional, assembly of EVs can boost affordability, while governments also need to work on developing sufficient charging infrastructure, decarbonising power grids and upholding sustainable practices in EV battery manufacturing.

“The speed of transition to EVs in Southeast Asia depends on [original equipment manufacturers’] plans, government policies and consumer attitudes,” said Abhilash Gupta, an analyst with global market research firm Counterpoint Research.

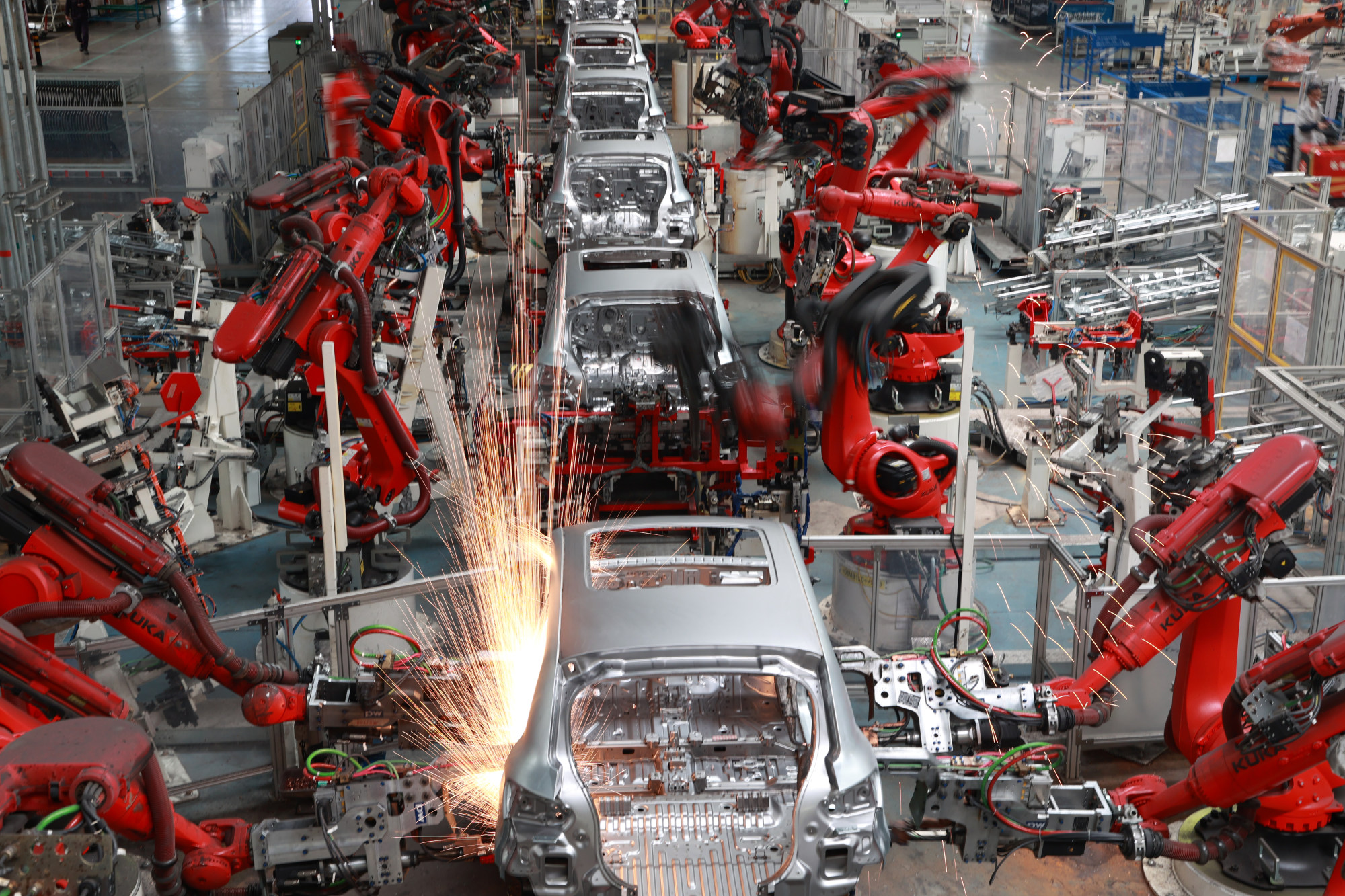

EV manufacturers have been quick off the mark to establish large production sites in the region, taking advantage of generous government incentives.

Chinese EV makers, including market giants BYD and Great Wall Motor, have committed to investing at least US$1.44 billion in their production facilities in Thailand, which is offering subsidies to manufacturers to build locally and incentives to consumers to make the switch.

BYD is pumping US$495 million into a new facility in Thailand to produce 150,000 cars annually from 2024, including for export to Europe. Once operational, it will feed into Thailand’s goal of raising EVs’ share of the country’s annual passenger-vehicle production – currently 2.5 million units – to 30 per cent by 2030.

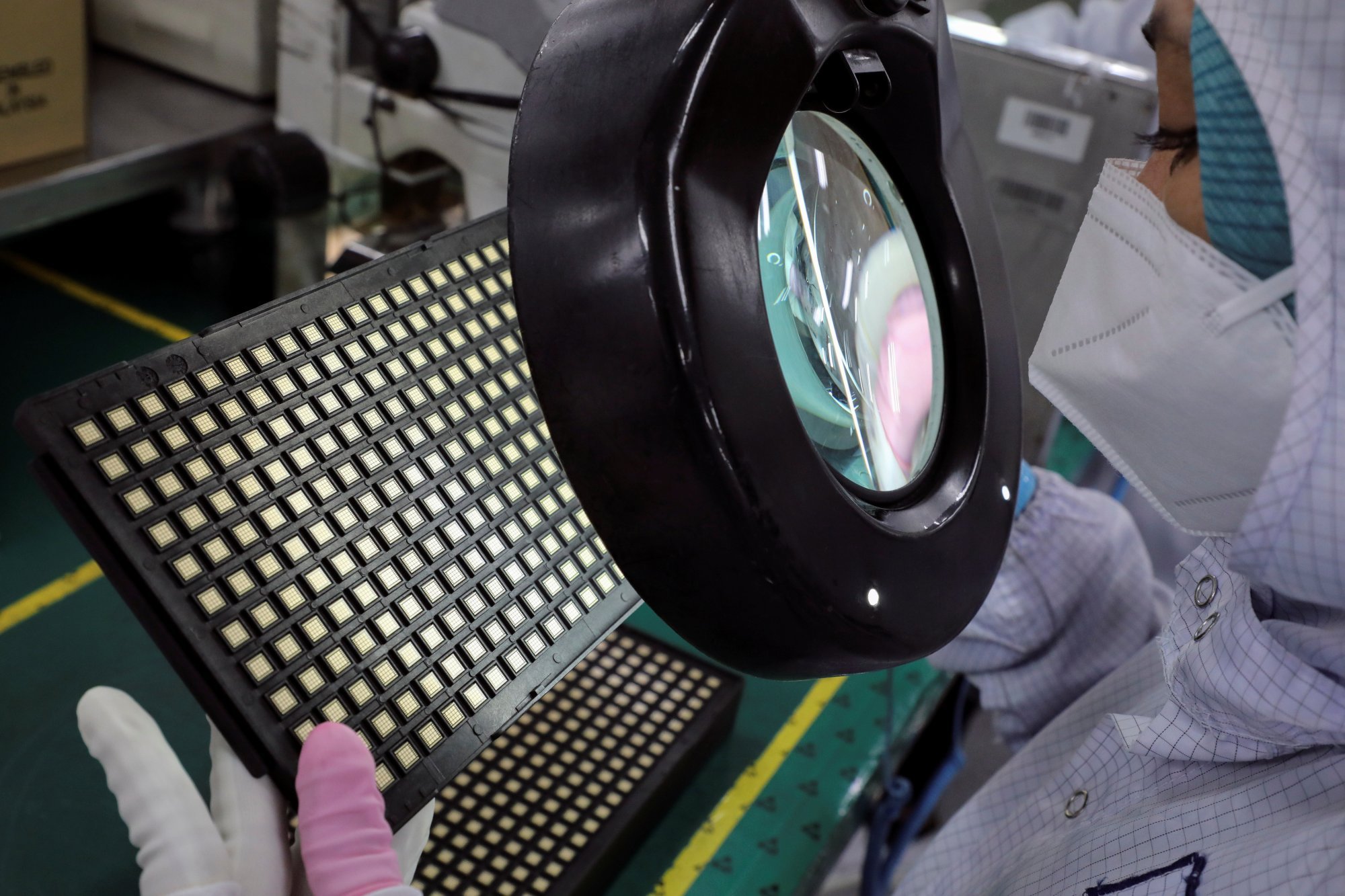

Investment, Trade and Industry Minister Tengku Zafrul Aziz said at least 42 Malaysian firms already supply parts to the EV production chain.

Malaysian manufacturers in the electrical and electronics sector are able to produce around 1,400 of the nearly 4,000 parts needed to build an EV car, he revealed.

“There is a realignment of the supply chain, and they also want the supply chain to be more resilient,” Tengku Zafrul told This Week in Asia. “One of the ways to be more resilient is to be closer to the source of the supply.”

Meanwhile, Tesla, he said, has made a commitment “to do other things” beyond setting up an office in the country.

The outlier in the EV race is Vietnam, which analysts say is less focused on attracting foreign direct investment and is instead more keen to build on the platform created by local EV champion VinFast.

But that does not mean that Vietnam can afford to neglect foreign investments in its EV push, especially if it wants to build as complete a supply chain as possible domestically.

“I think whether it is Vietnam, Indonesia or Thailand or Malaysia, they will all need to attract more foreign investment into their country to actually enhance the ecosystem that they have already,” said Ng, the economist at Natixis.

Chasing the green transition

But the shift to EVs also means the rise of a completely new industrial complex, which will lead to different jobs, supply chains – and a wholly new way to reap profits.

In just two years from now, passenger EV sales in Southeast Asia are expected to hit 169,300 units, up from 51,581 units in 2022, according to Bloomberg estimates. The figure is forecast to more than triple to 522,022 units in 2030.

By 2040, more than 2.9 million EVs are expected to be sold across the region, accounting for some 64 per cent of total vehicle sales: an estimated 4.5 million.

The question now is how well Southeast Asian nations will fare in their attempts to draw these lucrative investments.

Thailand is ahead of the pack in terms of attracting EV and EV-related investments, analysts say. As the region’s automotive hub, the country already has a strong reputation for building out ecosystems that support car production.

Despite the stumble in negotiations with Tesla, Indonesia’s vast nickel deposits continue to make it a viable option for companies looking to set up operations in the region.

Indonesia has the world’s largest nickel reserves but lacks lithium, a key material in EV production that Australia has in abundance.

Over the past three years, Indonesia has signed more than a dozen deals worth over US$15 billion for battery materials and EV production, including Hyundai’s first EV-manufacturing facility in Southeast Asia that launched in 2022.

The deals, however, also include several nickel smelters and processing facilities, raising concerns about Indonesia’s ability to amp up production while meeting global sustainability goals and requirements.

Malaysia’s semiconductor industry is its strongest selling point, but observers say that won’t be enough on its own to keep manufacturers from setting up shop elsewhere.

“You can always produce car chips and then ship them somewhere else. It’s not that hard to actually do that,” said Ng from Natixis.

You can always produce car chips and then ship them somewhere else. It’s not that hard to actually do that

Malaysia’s Tengku Zafrul however said it would not be so easy to replicate the country’s existing semiconductor ecosystem, and even if the chips went elsewhere, that would still make Malaysia part of the overall EV supply chain.

Claiming a bigger slice of the EV production pie is more of a focus for the country than pushing to increase consumer demand, it seems.

IEEFA’s Putra said two separate narratives dominate Southeast Asia’s EV race – one driven by market sales and production as in Thailand and Malaysia, and the other hingeing on natural resources, like in Indonesia.

“So I think what will happen is that both [narratives] will continue to move forward, but each country would have their own specific advantage,” he said.

Still, it is unlikely that any single country will claim a monopoly on the region’s entire production supply chain.

Multinational carmakers such as the Japanese marques have long used Southeast Asia as a manufacturing hub, with parts made in different countries at scale, both for use at their local assembly plants and for export, said Tham from ISEAS.

“If you leave it to countries, everyone will want the most valuable segment … you need [multinational corporations] that can see the region and position themselves, carve out the whole market,” she said.

“Asean’s shift to EV will provide a good neutral platform for manufacturing and exporting electric vehicles because the region is open to European, Japanese, Korean, Chinese and other carmakers at the same time,” said Jigar Shah, head of sustainability research at Maybank Investment Banking Group.

And for those who have already made the shift, they say there’s no going back to filthy fossil fuels.

“I’ll only buy electric from now on,” said Tesla-owning Bangkok resident Banjong Cheevamongkonkarn. “I’m sure future technology will just get better at charging, with longer range and costs will just keep going lower, which is better than wasting energy on the volatile petrol price.”