Why Germany has little choice but to continue to cosy up to China

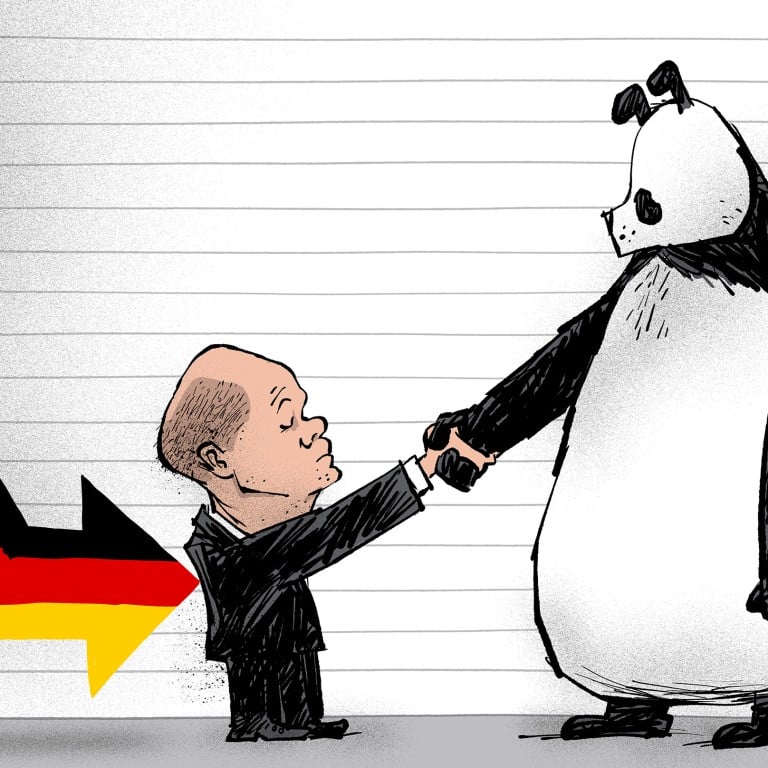

- The ugly truth is that the power of Germany’s economy is heavily connected to its business relationship with China and, with that, Scholz’s political fortunes

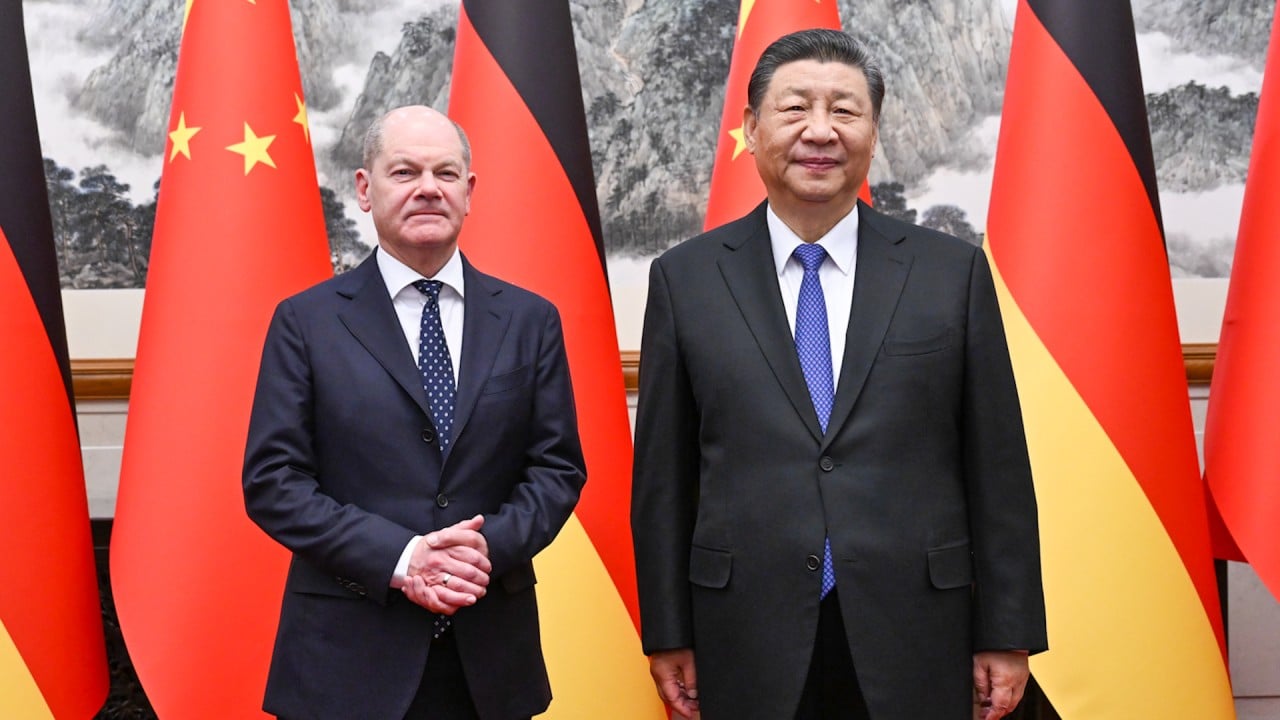

“The Russian war of aggression against Ukraine and Russia’s rearmament have had a very significant negative effect on security in Europe,” Scholz said at the meeting at the Diaoyutai state guest house. “They directly affect our core interests.”

Xi mainly repeated well-known phrases. “Together we can breathe more stability and security into the world,” he told the chancellor – and said China was not involved in the Ukraine crisis.

Xi’s remarks that Sino-German cooperation was not a risk, but an opportunity, will have been music to Scholz’s ears.

That is particularly so given that his policy is a de facto continuation of Angela Merkel’s pragmatic approach to China, which she championed during her 16 years in office, delivering immense prosperity for both sides despite critics in Germany and Brussels alike.

If there had been any doubt that Scholz is inclined to maintain the status quo, it is now gone. His visit confirmed that the economy takes precedence – evidenced in the fact that he spent three days in China, his longest bilateral visit since taking office.

Tellingly, top German business leaders travelled with Scholz, plus the ministers for agriculture, the environment and transport – but not the foreign minister. Scholz also made it clear there was “no interest in an economic decoupling from China”.

Thus, the message to Beijing was clear: the German chancellor is travelling to three different cities over three days with a delegation primarily focused on economic issues, before addressing a few other critical issues with Xi.

It is unclear whether Scholz even brought up human rights issues during his visit. So how did Berlin go from the harsh tones towards China during the last election campaign and, indeed, over the past year – and which included terms like “values-based” foreign policy – to a business-as-usual approach?

But the main rationale behind Scholz’s modus operandi is self-preservation. The grand coalition’s poll numbers are abysmal. Scholz’s Social Democratic Party finds itself at a low of 15 per cent, trailing the far-right Alternative for Germany (18 per cent) and the Christian Democratic Union of Germany, on 30 per cent, according to Politico.

Scholz’s approval numbers are equally bad. In a Statistica poll in January that asked Germans how he was doing as chancellor, 67 per cent said “badly”. Two years ago, 71 per cent thought he was doing “well”. If an election were held tomorrow, Scholz would most likely no longer be chancellor.

As in most industrialised nations, Germany’s elections are primarily decided by economic circumstances and the leader’s persona. Much to Scholz’s dismay, the German economy has been in crisis for four years. Last month, the country’s leading economic institutes had to correct their growth forecasts for the year: down from 1.3 per cent to just 0.1 per cent.

Scholz likes to blame others for this – primarily Russian President Vladimir Putin, who caused an economic shock with his war in Ukraine. While that may be factually sound, it’s not a valid excuse. Other countries have also been affected – but their economies have recovered faster.

The ugly truth is that the power of Germany’s economy is heavily connected to its business relationship with China. In 2019, German exports accounted for 48.5 per cent of all European Union exports to China.

Despite ‘de-risking’ talk, Scholz’s Germany has not turned away from China

Without this alliance of convenience, the German economy would find itself in a real crisis, one that could not be mitigated before the next election and Scholz, like Merkel before him, knows this.

But Germany will not be part of it. With the harsh economic reality hitting home, Scholz has been forced to abandon any idealistic views in favour of realpolitik – for the country’s sake, and his own.

Thomas O. Falk is a journalist and political analyst who writes about German, British, and US politics