Hell and high water

Even the dogged pilgrim can pass without noticing the two monuments honouring the first man to conquer the Yangtze River.

Grave plot 8496, in Section 12 of Hong Kong Cemetery in Happy Valley is difficult to locate among the sombre rows of tombs. The pollution-belching traffic heading into Causeway Bay along Wong Nai Chung Road has left its mark. The headstone is streaked with a black residue, like a weeping mourner's mascara, and the name of the deceased has been smudged by decades of wilting summer heat and sulphur-laced rains.

After two afternoons of searching, I locate it and scrape clear the obscured words on the headstone's inscription. The grains blunt my fingernails and turn them black, and I soon give up, satisfied anyone determined to pay their respects will be able to read the epitaph.

Along with dates, the grave inscription reads: 'In memory of Captain Samuel Cornell Plant; Upper Yangtze River Inspector of the Chinese Maritime Customs. The first to command a merchant steamer plying on the Upper Yangtze River (1900).

'Also in Memory of Alice Sophia Plant, Captain Plant's wife and devoted companion throughout his 20 years of toil on the dangerous section of the Yangtze River between Ichang and Chungking.'

I prop flowers against the grave and on the card I write, as instructed: 'To Cornell and Alice. Remembered by the family with great pride.'

I snap a picture, pat the headstone and head to the mainland, to search for the second monument to this remarkable riverboat captain, who is still remembered, albeit modestly and by contrasting communities located worlds apart.

What's more, when the many mourners left this graveside 90 years ago, two took with them a mystery that is yet to be solved.

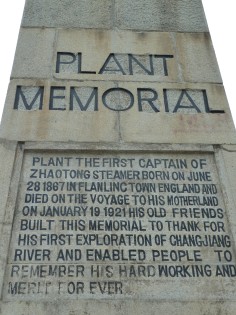

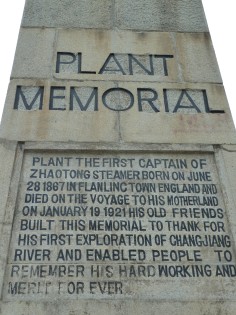

ONE THOUSAND kilometres north of Happy Valley, in the middle of Xiling Gorge, I stand on the fecund south bank of the Yangtze and, under a sultry, smog-leaden sky, I spy through binoculars an imposing column of granite stone. I can make out through the gloaming the large inscription: 'Plant Memorial'.

Like the Hong Kong headstone, if you were not seeking the monu- ment you would glide obliviously by, like the ships passing through its shadow.

There is no other landmark like it on the 6,500-kilometre-long river, which stretches from its source high up on the Tibetan Plateau to the sea at Shanghai; a watercourse that for centuries has been the origin and backdrop to much of China's history, carrying on it life, death, myths, legends, warlords and armies, heroes and invaders, tragedies and fortunes. Indeed, given the excesses of the colonialists over the past two centuries, there are few monuments to remember foreign friends on Chinese soil.

Inspirational political thinkers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels each have a statue in Shanghai's Fuxing Park, but neither visited the country. There is a stone tablet at Peking University dedicated to Edgar Snow, the American journalist who published often controversial work on Mao Zedong and the communist revolution. Norman Bethune, a Canadian physicist and communist sympathiser, has a memorial next to his grave in the Revolutionary Martyrs' Cemetery in Shijiazhuang, Hebei province. His tomb lies opposite a statue of Dwarkanath Kotnis, an Indian doctor honoured for his humanitarian contribution to the Chinese during the Sino-Japanese war who is buried in the same graveyard. General Joseph Stilwell, the American chief of staff to Chiang Kai-shek, has a museum dedicated to him (thanks to his daughters, who lobbied for the exhibition) in the Chungking (now Chongqing) house in which he was billeted during the second world war. Yet none of these tributes stand as grand and tall as the 30-foot obelisk erected to honour Plant. That it still exists at all is remarkable.

Built in 1923 on ground prone to tremors and devastating landslides, it has survived vandalising Red Guards and the Yangtze dam flood.

When cherry-picking government archaeologists were sent to iden- tify which few relics- from hundreds of thousands- should be saved from the lake set to rise behind the Three Gorges Dam, they slapped a rescue order on the obelisk and demanded it be moved high above the new water line. They did so because Plant had won the first major battle in the long war against the raging torrents cascading through the Three Gorges.

Brimming with Himalayan snow melt and heavy rains, many of the Yangtze's rapids were caused by detritus from landslides, the Hsin Tan Rapid- here in Xiling Gorge- being one of the most notorious takers of life on this stretch of the river. The gorges were peppered with hidden reefs, rip currents, treacherous shoals and strength-sucking whirlpools.

The signature sound echoing off the cliffs and bluffs was the whoosh and roar of white water. For centuries, the boatmen and trackers who waited on the banks to haul cargo junks over the foaming chaos, dubbed this place the 'gates of hell'. They clung to superstitions to ensure safe passage and muttered the saying: 'Each and every hazard is enough to make the devil frown in despair.'

Cargo boats and their crews were lost with alarming frequency and, as a result, the Sichuan basin remained a backwater. Trackers regularly fell from the tow paths, breaking limbs or simply being swept away.

Successive leaders offered plans to dam the torrent, to temper its deadly spirit. Sun Yat-sen wrote about such a plan in his 1919 'A Plan to Develop Industry' paper and Mao lyrically dreamed of a Yangtze dammed in his 1950s Swimming poem. Premier Li Peng finally gave the construction go-ahead for the Three Gorges Dam in the aftermath of the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, a calculated distraction to boost a shocked and demoralised nation.

Yet, two decades before Sun's blueprint and three decades before Li was born, the river met its match in the determined Plant. He beat the waters into submission and prized open the Sichuan hinterland.

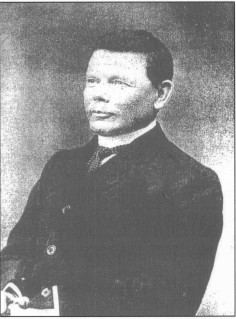

PHOTOGRAPHS OF THE captain are as rare as his 21st-century admirers. What illustrations exist show an unassuming, reticent, short, plumpish, pipe-smoking man- a most unlikely intrepid son of the British Empire.

He was born in August 1866, in Framlingham, Suffolk, in the east of England, to a seafaring family. He served on blue-ocean vessels before being posted to Persia, where he charted the raging rivers of Iraq and Iran, including the Euphrates. There, he met and married his wife, Alice.

When they moved to the Middle Kingdom, the couple fell in love with the Yangtze and Plant's pioneering work in the Three Gorges defined him.

He had been enticed to China by a Scottish merchant, Archibald Little, during a meeting at the Oriental Club in London in 1899. Little was from a prominent Shanghai expatriate family and perhaps the first to recognise the trade potential of the Sichuan basin. He had been trying for decades to conquer the Three Gorges rapids without trackers and make Chongqing a viable river port.

Little explained to Plant that the trackers were essential but made travel slow and did not guarantee safe passage. Junk captains and their crews relied as much on their gods and rituals as they did on their boating skills, but none delivered, he said. All told, trade was unprofitable.

'Can you help?' Little asked Plant, who would later observe that one junk in 10 was badly damaged by the hazards and that one in 20 was wrecked, with all cargo and many hands lost. He would also note that less than 20 per cent of the junks that attempted the journey to Chongqing from Yichang reached their destination, and every one of them- filled to the gunnels with crew, their families and cargo- did so after having survived a near-death experience.

Having just conquered the rapid-strewn Karun River, in modern-day Iran, Plant agreed to take up Little's challenge.

He travelled first to Clydebank, Scotland, to oversee the building of a boat specially designed for the Yangtze quest and arrived in China later in 1899 to take charge of the Pioneer, a side-wheeled, shallow-draft 160-foot steam boat, which had been shipped to the Far East in parts and assembled in Shanghai.

In June 1900, Plant gripped the helm at Yichang and pointed the Pioneer's bow in the direction of Chongqing. The voyage took a full three days, spread over a week, of tight turns to avoid rocks in the cascades, the steam turbine engine huffing and puffing, and relentlessly turning the screaming propeller.

The Pioneer made it through and, for the first time in the river's long history, Plant succeeded in docking a large vessel at Chongqing without having had to use trackers. With him he brought the age of steam and 19th-century industrial modernity, which he anchored deep inside China's western interior.

The Chinese were in awe of his fearless approach to the devouring waters and, with fondness, called him Pu Lan Tian. He was dubbed Dragon Dodger by his expat peers.

After accomplishing his mission, Plant set about charting the gorges. He bought a house boat, called Junie, on which he lived with his wife, and from its decks he conducted detailed hydrographic surveys.

He designed his own boat, the Shutung, made in England and also shipped out in parts, and with it he ran a Yichang-Chongqing-Yichang passenger and freight service, which took one week to sail up stream and three days down.

A map-maker and navigator extraordinaire, he was headhunted by Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs, a service set up under the Treaty of Nanking in 1842 and run by colonials to collect customs duties for the Chinese government. Appointed 'senior river inspector, upper Yangtze' in 1910, he compiled the Shipmaster's Guide, the first pilot book for that stretch of the river. It became an essential part of a navigator's kit, showing captains in numbered diagrams (for non-English readers) how to approach a rapid and follow the axis of its current, and- crucially- how to back out of the white-water maelstrom if things started to go awry.

The book could be found on the bridges of ships and junks for more than half a century, its pages dog-eared and marked with pencil by many a nervous but grateful skipper.

Merchants and officials feted the Plants up and down the river and denizens of the Yangtze saluted the captain for having saved the lives of relatives, friends and themselves.

In May this year, the Ministry of Transport's Administration of Navigational Affairs claimed in a report that 1.5 billion tonnes of cargo was carried on the Yangtze River last year, making it the busiest freight waterway in the world, ahead of the Mississippi in the United States and the Rhine in Europe. The dam, which went into operation in 2006, may have deeply submerged many of the worst hazards but the authorities still use the navigation system and rules and regulations designed by Plant. His nautical marks- black triangles and balls- are dotted along the banks; his colour-coded buoys, white for the north bank and red for the south, keep the fleet on course. And his Shipmaster's Guide and charts remain the basis on which modern pilot manuals are written.

'HERE COMES the ferry,' says my driver-cum-river guide, throwing his cigarette out of the window on to the slipway and making ready for the 10am departure to the small village of (new) Xintan.

On the opposite bank the monument looms large. Forty metres above us on the steep banks is a tide mark. Looking up and down the river, the two-tone effect is stark.

'The water has gone down to help stop the drought [and threat of famine] down stream,' says the ferryman, as he collects fares, nodding eastwards, towards the dam a day's steam away.

The crossing takes less than 10 minutes but it is the only way to bridge the river this far inside Xiling Gorge, and reach the monument.

Xintan was once a community of 20,000-plus people with coal dust and the hillside soil ingrained in the lines of their calloused hands, mining and farming being the two main industries here. Others fished the river.

In the mid-90s, officials arrived to tell of a big flood. They returned on a regular basis over the next few years, offering compensation money. Then they ordered the villagers to leave. Most villagers took the 10,000 yuan per person cash handout and moved over the mountains to live in big new cities far from their bucolic waterside existence.

The officials returned in 2004, this time in hard hats, and blew the town to smithereens, bricks and mortar and several millennia of memories turned into rubble and river bed.

A thousand villagers stayed on to farm the ancient terraces and work the small coal seam in the mountainside. But so small now is the community, the ferry offers only three crossings a day.

'Be back by 2pm,' says the ferryman, as he lets down the ramp and waves us off. We drive up a small road full of switchbacks and there is a whiff of freshly dried concrete and paint mixed in with the verdurous riverbank aromas.

Like many of the remaining villagers, Qu Yuan used his compensation to build a home high above the tide mark. He has turned the ground floor into a modest restaurant and is sitting outside, on a rickety bamboo chair, smoking and chatting with locals.

'It's to remember a foreigner who saved lives on the river. I think he was Japanese,' Qu says of the imposing stone tribute 150 metres down the road. Semi-literate, Qu says he has never been able to read fully the bilingual inscription. 'All I know is that he was important enough to be saved from the old town when the [dam flood] waters came. The gov- ernment came and moved it up to this spot. It was down there, at the water's edge at Dragon Horse Stream, on Turtle Island,' he says, pointing down the mountain to a humped-back promontory with a telecommunications mast, which is reflected in a flat, mud-coloured lagoon.

As a child he played at the water's edge in the once bustling village, he says, and the Plant Memorial was a feature of his youth. Then as now, he didn't take much notice of it, he admits.

'[The local government] came, I think in 2002, and they started to move the monument block by block up to here and then put it all back together,' he says.

His wife stands and listens and then suddenly becomes excited, saying she remembers a man in the old village, an amateur historian, who wrote a small book about Pu Lan Tian- and that somewhere among the family clutter, she thinks, there is a copy.

As his wife disappears to look, I explain to Qu that Pu Lan Tian was not Japanese but British. The monument was erected two years after his death, and was paid for with money collected from the Chinese Maritime Customs Service and local boatmen.

Qu's wife comes out wiping her hands on an apron. Some customers have arrived for lunch and she says she can't find the book.

We walk down to the granite stones, which still bear pockmarks inflicted by Red Guards. In 1968, they tried to blow up the tribute to the colonial invader, but it was so well constructed the explosives failed. They then set to work erasing memories of his existence with hammers and chisels.

We read the inscriptions and I refer to my notes with the original wording, filling in the gaps. I tell Qu the Kuomintang government awarded Plant the Order of the Chia-Ho for his services. And that, when he retired from the Chinese Maritime Customs Service, in 1919, the government and local people built the Plants a cottage at the top of a nearby cliff, overlooking the infamous Hsin Tan rapid, now submerged.

It became the custom for an up-stream shipmaster to sound his siren after passing through the turbulence, whereupon Plant would wave a handkerchief or his hat from his terrace in acknowledgement.

A newish brass plaque, on the first level of the marble plinth, explains why it was saved: 'The Plant Memorial is an important historic site and mark on the shipping history of Three Gorges region.'

In 1921, the Plants decided to visit England for a holiday before returning to Xintan to live out the rest of their lives. In Shanghai, they boarded the Blue Funnel line's SS Teiresias, which was to take them to Europe via various ports. En route to Hong Kong, however, Plant, aged 54, came down with pneumonia. He died at sea on February 26, 1921.

The ship's surgeon wrote in his report: 'I was told that he had been ill for a week and that he was suffering from a malarial attack, but, on examination, an advanced R:lobar pneumonia was evident. Temp. 103.6. Pulse 86. Resp. 34. Routine treatment was at once commenced, but it was obvious that the odds were against the patient.'

Tragedy struck again when Alice also passed away - just two days after the ship docked in Victoria Harbour; she, too, died of pneumonia, but perhaps pining for her lifelong companion exacerbated her condition. They were buried together in Happy Valley.

'Do many people come to visit the memorial?' I ask.

Qu shakes his head. 'We do get more and more tourists coming in cars. But I don't think they are coming to see this,' he says.

'It is a good thing, the dam. There is more money in the gorges now.'

On the tide of the rising waters have come engineers and factory owners. Land reclamation is everywhere and docks and jetties are springing up to service the new industries.

'But there are more landslides. And the biggest change is the noise,' says Qu. 'We used to hear the rapids all the time; it sent you to sleep as a kid. But now we can't hear them.'

At Yichang docks, I board the MS Yangtze Explorer, a five-star cruise ship, for a four-day journey upstream to Chongqing in the height of luxury. American millionaires are my on-board company.

I throw my bag on to the king-size bed and pull out a dog-eared photocopied selection of colonial literature. Most of the early English-language books about the Yangtze burst with righteous, flowery prose and were vanity published by missionaries, merchants and officials who wrote about their extravagant boat trips up the vener- able 'Changjiang'.

Plant was urged to write a travel-guide companion to his pilot book. The long out of print Glimpses of the Yangtze was arguably the first guidebook for tourists about the Three Gorges. Plant's style is functional and utilitarian; the opening line reads: 'The best way to see the glories and the dangers of this mighty river is to travel in a native boat.'

'How much would they want to take me up to Chongqing,' I ask Willy, the ship's tour guide, pointing to a small sampan moored in a gully opposite the cruise ship. He looks at me in astonishment.

'Impossible!' he says.

We sail under the Plant Memorial at night, when most of the passengers are tucked up in bed. I sit in the dark, on my private starboard balcony, scouring the banks - but I fail to spot it.

Next day, I ask for an audience with the ship's captain and am taken to the fly-blown, smoke-filled bridge, where four crew members suck on cigarettes and look at me with suspicion. From the bridge, a 180-degree view shows the Yangtze awash in commerce. Coal barges and container ships queue to dock and unload at power stations and anonymous factories; smaller vessels weave in and out of the wakes and fisherman cast nets; on the river banks, welders' torches flash and fizz as they piece together more ships being readied to join a fleet sailing full steam towards China 's future.

Captain Li Junpin says, yes, he has heard of Pu Lan Tian, the foreigner who made the river safe, and he remembers the pilot book.

'But these days,' he says, nod- ding to the blipping green radar and grey GPS screens 'we have more modern equipment'.

THIRTEEN THOUSAND kilometres away, in the small Cotswolds village of Gotherington, disapproving clucks can be heard when the Women's Institute chairwoman decides, given the busy schedule, to do away with the traditional singing of the anthem of middle England, Jerusalem, and instead crack on with tonight's guest speaker, Michael Gillam.

'Michael is from down the road, in Prestbury, and his wife, Janet, is a WI member. Michael has come to talk to us about the Dragon Dodger. A fascinating title but I have no idea what it is about... Michael, all yours, ' she says and the hall erupts into applause.

'Can I first ask a question: have any of you been to China?' asks Gillam, who is dressed smartly in blazer and Royal Navy tie replete with his veterans' badge. 'Did any of you go up the Yangtze?'

Several hands go up and 60 pairs of ears go on the alert; China has been a topic very much on the mind of this influential demographic for the past decade.

'Well if you did, you would, if you had been looking, perhaps have spotted this,' continues Gillam, and he switches to a slide of the Plant Memorial. For the next hour, the life and times of Plant and his work on the Yangzte 90 years ago are brought alive and digested by a captivated audience.

Gillam is Plant's nephew and I first met him in January, after a long search for the captain's relatives.

At his home, Gillam spreads out his Plant memorabilia, much of it contained in the captain's old sea chest. Part of the hoard is an ink- well, inscribed with the words, 'To the Dragon Dodger - a small memento of many kindnesses while Dodging the Dragon'. Chinese scrolls, logbooks and albums of rare black and white photos of junks being hauled by trackers, whitewater and the river traffic are also among the bounty.

Gillam, a 79-year-old former British Royal Navy lieutenant commander, has been immersed in the life of his uncle since he was handed his possessions 20 years ago by his parents. He gives his slideshow talk a few times a year to small community clubs and has passed on many Plant facts to Britain's National Maritime Museum and other like-minded organisations.

Furthermore, his hobby has now become a missing persons' riddle, which has seen him scour the world for an answer.

He shunts around piles of documents, clip folders, boxes and albums on his dining room table.

'Ah, here it is,' he says. 'Now, I have to point out that this is only circumstantial evidence. We do not have, as yet, anything conclusive,' and he hands over with mock ceremony a black and white photograph of two pretty Eurasian girls, no older than seven or eight.

The relaxed smiles and serene eyes of the neatly dressed sisters stare back silently from another age, a time of colonial upheaval and of a China - then as now - in transition.

'This is Clara and Isobel, and we believe [they] could be the girls the Plants adopted.'

According to a report of the Plants' funeral published by the South China Morning Post on March 3, 1921, 'the chief mourners were the two Chinese adopted daughters of the deceased'. The girls were, wrote Yichang British consul Charles J.L. Smith in a letter to Plant's brother, orphans the couple were taking to Britain for their education.

Smith wrote: 'The two girls were waifs bought by Mrs Plant a number of years ago and brought up by her as servants in her own house. They were too young to marry and therefore Mrs Plant was taking them home with her, intending to bring them back at the conclusion of her furlough, after which she intended to marry them off and give them a small dowry.'

After the funeral, the girls were sent back from Hong Kong to the Church of Scotland Mission in Yichang, wrote Smith, under the guardianship of a Mary Emelia Moore.

'When the girls grew up, they moved to Chengdu and Ms Moore fled there from Yichang with the advance of the Japanese in 1937-38. She then moved to New Zealand,' says Gillam, his eyebrows raised in puzzlement as he places the papers back in their folders.

'It would be great to find out exactly who the girls were and what happened to them. If you find anything out, do let me know ...' says Gillam, whose global quest to track down the girls has seen him travel as far as New Zealand and Hong Kong.

He stares at the photos of the Plants' headstone.

'The trail, quite literally, goes cold at that graveside in Happy Valley cemetery.'