Bernanke may have hidden agenda in printing money

When US Federal Reserve chairman Bill Bernanke announced his latest exercise in money printing last Thursday, he said he would keep the presses running until the US job market begins to improve.

The idea is that by buying US$40 billion in mortgage-backed securities each month, the Fed will flood the US financial system with fresh liquidity and push down mortgage rates, encouraging businesses to invest and home buyers to return to the market.

If that's the Fed's real objective, it's unlikely to succeed. Mortgage rates are already at a record low, and with benchmark interest rates at zero, they are hardly going to go much lower.

What's more, two previous rounds of quantitative easing, plus the Fed's ongoing "Operation Twist" programme of securities purchases, have had little impact on jobless levels.

It's true that the headline rate of unemployment has fallen from almost 10 per cent two years ago to just over 8 per cent. But the decline is misleading. People only count as unemployed if they are actively looking for work. In the past couple of years, many have given up the search, dropping out of the official unemployment statistics. As a result, the labour force participation rate has fallen and the number of jobless Americans has continued to rise.

There's little reason to believe that the latest round of quantitative easing - dubbed QE3 - will be any more effective.

But that won't deter the Fed because the real objective of QE3 may not be to create jobs so much as to create inflation.

With the US struggling under a total debt burden - public and private - equal to about 360 per cent of gross domestic product, the Fed is desperate to boost nominal GDP in order to shrink the relative size of the debt mountain. If it can't do that by promoting real growth, the Fed will settle for pushing up inflation, which also boosts nominal GDP.

According to James Rickards, the chief operating officer of hedge fund JAC Capital Advisors and author of the 2011 book Currency Wars, the Fed is aiming to produce an inflation rate of 4 per cent, double its official target and more than twice the benchmark long-term interest rate. The objective is not only to cut the country's real debt burden but to shock consumers into spending by scaring them that prices are going to be even higher in the future.

But stoking inflation by printing money can be difficult when consumers are busy deleveraging and a shell-shocked financial system is reluctant to create fresh credit. Even after two previous rounds of quantitative easing, the US consumer inflation rate was just 0.6 per cent last month.

However, Rickards says the Fed's plan to push up prices can still work, albeit indirectly. He argues that the vast quantity of liquidity pumped out by the Fed has indeed produced inflation, just not in the US.

As it has flooded the world with US dollars, exporting countries led by China have embarked on money-printing exercises of their own in order to prevent their currencies strengthening against the US dollar, which would severely damage their export industries.

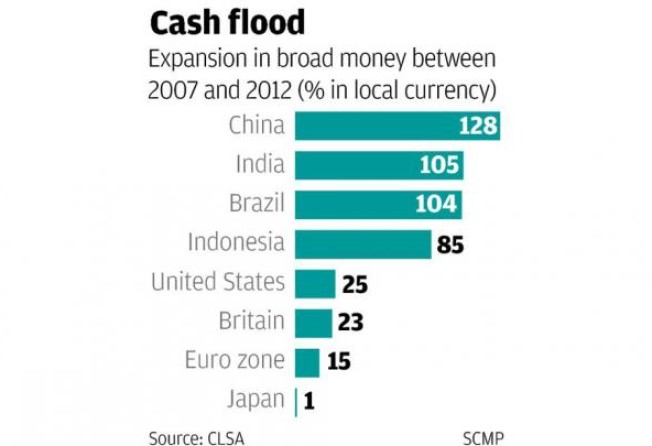

The effort has been enormous. According to data compiled by brokerage house CLSA, between 2007 and 2012, US broad money supply expanded by US$2.36 trillion as a result of the Fed's quantitative easing.

Over the same period, China's broad money supply has ballooned by an astonishing US$9.02 trillion (see chart).

Rickards says that expansion has proved hugely inflationary for the Chinese economy, driving up wages and causing unsustainable bubbles in infrastructure investment and the property market.

In short, he says that for China, maintaining a cheap currency is proving very expensive, and Beijing must either allow its currency to appreciate or face mounting inflation at home.

Either way, the price of China's exports to the US will increase. And that, believes Rickards, is exactly what the Fed wants to see.

Bernanke may not be able to drive up US inflation directly, but he can exploit the managed exchange rate mechanisms of countries like China to export inflation abroad, and then re-import it in the form of more expensive imports, so achieving his objective of pushing up consumer prices at home.

"The US calls China a currency manipulator," says Rickards, "but the US is the greatest currency manipulator in the world."

Rickards believes the Fed's plan may prove too effective, noting that once it hits 4 per cent, inflation could very rapidly rise to 8 per cent.

But it is only fair to point out that other observers disagree. They argue that QE3 is failing to produce inflation either in the US or China, and that the greatest danger facing the world economy is not rising prices but looming deflation.

We'll examine their arguments later in the week.