Pearl may be found in Oi Wah Pawnshop flotation if it turns into a shell

The stock market flotation of the Oi Wah Pawnshop chain may make little sense for shareholders except if it becomes a shell company

A pawn shop is going for a listing. That's interesting. Its shares have been over-subscribed 1,000 times. That is even more interesting.

Well, wait till you read the prospectus of Oi Wah Pawnshop Credit Holdings.

You see a teeny tiny business raising a teeny tiny sum for a teeny tiny expansion. You see a big why.

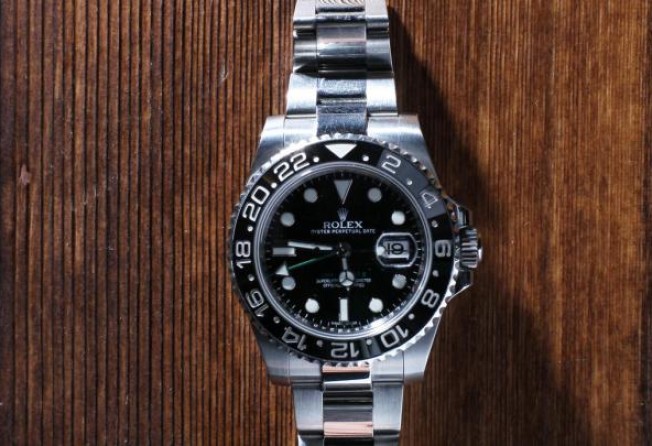

For the lucky ones who have never traded with a pawn shop, a brief explanation is necessary. Behind the little green doors is a guy who has just lost his shirt in a soccer bet. He pawned his Rolex watch for HK$$100,000 - the maximum allowed by law - to make another bet.

If he is lucky and wins, he would pay Oi Wah HK$103,500, the original loan plus the 3.5 per cent interest rate allowed by law, within a month to retrieve his Rolex. If not, the pawnshop will pocket the watch.

It is a juicy business, if tiny. Oi Wah, the largest in the industry, recorded HK$66.3 million in revenue and HK$33 million profit in the financial year 2012. That translates into a daily income of HK$15,136 for each of its 12 shops!

Oi Wah's consultant, Ipsos Hong Kong, said the city's growing poverty rate and widening wealth gap will sustain the demand for pawn loans to pay rising bills. Economic recovery will not change that, thanks to the impulse to gamble and shop.

However, while the number of poor in Hong Kong has certainly increased in the past few years, the growth of Oi Wah is far from impressive. It has managed to expand its business by 6.4 per cent in the six months before applying for a listing only by aggressively pushing into the mortgage business.

The result is HK$38 million in mortgage loan receivables, a HK$20 million cashflow shortfall and a HK$18.5 million bank loan (part of which was used to fund a HK$2.9 million dividend).

Oi Wah is selling its stake for a tiny sum: HK$64 million. Of the HK$98 million proceeds, 35 per cent will go to the sponsor, lawyers and auditors.

Oi Wah said it would use a total of HK$56 million to grow its loan portfolio, in particular the mortgage business. In the highly competitive and price-sensitive mortgage market, that is not even a drop in the ocean.

The rest will go for TV advertisements and a new customer service centre in a commercial building, to provide "discreet" service. (I thought the green door was discreet enough.)

In return for this "negligible" sum, Oi Wah had to make some undesirable disclosures. It had to report to the police that it has breached the HK$100,000 single loan statutory limit on many occasions by offering loans as high as HK$500,000.

It had to disclose the size of unlawful goods pawned, a breach of a tenancy agreement, an illegal structure in a shop and other infractions.

How this tiny business is to prosper with the help of a listing status is anyone's wonder. Its shareholders will have much more to gain if they are to sell its listing status as a "shell" in the future.

A "clean" shell company with zero liabilities can now easily fetch HK$350 million, thanks to the strong desire by mainland corporates to list in Hong Kong. Even a shell in the much less liquid GEM market can ask for HK$150 million.

This price can only go up. While Beijing is re-vetting each of the 800 IPO applications pending, the door to the US market is almost closed after a chain of frauds by mainland entrepreneurs.

Oi Wah fits the criteria for a good and therefore pricy shell in many ways.

First, it has a single and simple business. The regulators have barred shell companies from receiving any asset injections within 24 months of any ownership change.

During that period, the lending business would save the listed shell from turning into a "cash company", which would have to be de-listed under the rules.

Second, it had no factories. Fixed-asset valuation and disposal can be troublesome and unwelcome chores to a potential purchaser.

Third, it had little bank loans or hidden liabilities.

Fourth, the Chan family, including the father, one son and three daughters, controls 75 per cent of Oi Wah and all the executive board seats, making negotiation much easier. Mainland buyers are terrified by the Grand Field fiasco, in which a fight between the shell buyer and remaining shareholders resulted in a two-year trading suspension. The Chans' absolute control is very appealing.

Exit is quick, as well. Various shells have changed hands only a year after their listing. Why bother to wait for organic growth, if any?

I am sure there are many advisers to tell the Chans about the opportunities.