Irrational financial markets disprove wisdom of crowds

Investors panic and sell shares over events like the US recovery and the slowing Chinese economy that should be welcomed, not feared

Anyone who still believes in the wisdom of crowds should take a look at what has been going on in the financial markets.

A market, after all, is made up of a crowd of investors, and its price fluctuations represent swings in the aggregate sentiment of that crowd.

But although prices impart this information with great efficiency, what the information tells us is that often the aggregate behaviour of a crowd of investors is not rational, let alone wise.

Just consider what has been happening recently in Asia's financial markets. Yesterday, Hong Kong's benchmark Hang Seng Index dropped by 2.2 per cent, bringing its cumulative fall over the past four weeks to 11 per cent.

It is not just Hong Kong's market that has taken a hammering. Mainland stock markets are down. too. And in Southeast Asia, share prices, bond markets and currencies have all fallen steeply.

There are two main reasons cited for this rout: fears that the US Federal Reserve may soon begin "tapering" its latest round of quantitative easing, and concerns that the Chinese economy is slowing.

Tapering first: at the moment the Fed is buying US$85 billion of debt securities a month from the markets, effectively injecting an equal amount of cash into the financial system in an attempt to support economic activity in the United States.

Last month, however, Fed chairman Ben Bernanke said that as the US recovery gathers steam, over the next few months the Fed may begin reducing its asset purchases.

In a rational world a recovery in the US economy would be good news, but Bernanke's remarks triggered something of a panic among investors, who assumed they prefigured a change in Fed policy and concluded that without the support of quantitative easing, the price of risky assets in Asia would tumble.

Yet, in reality, any significant change in Fed policy is unlikely in the near future. Above all, the Fed is watching the state of the US labour market. And with the unemployment rate at 7.6 per cent in May, up from 7.5 in April, labour force participation down over the past 12 months, job creation modest and pay only rising in line with the subdued rate of inflation, the Fed is far from ready to begin scaling back its quantitative easing.

Indeed, even though it is irrational, investors' fear of tapering could delay the act itself. Over the past six weeks, concerns over tapering have pushed the yield on 10-year US Treasury notes up by 0.6 of a percentage point, from 1.6 to 2.2 per cent.

That increase has pushed up mortgage rates, threatening to strangle the nascent recovery in the US property market, which is generating around a quarter of new American jobs. As a result, tapering is a distant prospect. At the very earliest it won't begin until autumn, and quite possibly not until next year.

Even then, when the Fed does begin scaling back its asset purchases, say to US$65 billion a month from US$85 billion, it will still be easing - just a touch less aggressively than before.

And with much of the cash generated by current asset purchases remaining at the Fed in the form of excess bank reserves, the impact of tapering on financial market liquidity is likely to be small.

So market fears of Fed tapering look overblown. That still leaves worries over a slowdown in China's economy.

After a series of weak data releases in recent weeks, analysts have been downgrading their growth forecasts for China, with many now looking for output growth this year of just 7.5 per cent, down from 7.8 per cent last year.

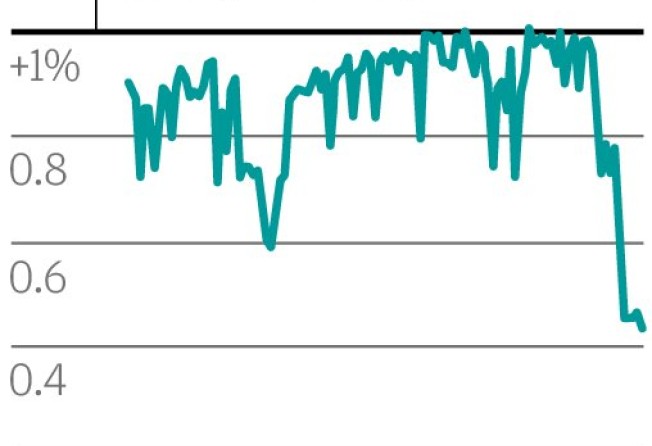

In response, investors have trimmed their exposure to Chinese stocks listed in Hong Kong, and the yuan's exchange rate has retreated from the strong side of its permitted trading band against the US dollar (see the chart), indicating a diminishing enthusiasm for holding the currency.

Both reactions seem sensible in the short term. In a slower economy, earnings growth will be harder to generate, and currency appreciation less likely.

But in the longer term, a Chinese slowdown should be reason to celebrate. For years economists have been telling us that China's expansion is unsustainable, and that the pace of growth needs to slow if the economy is to avoid a crash landing.

Hopefully that long-awaited slowdown, bringing growth into line with Beijing's target rate, is now happening. For rational investors, that should be good news, not bad.