India's hard lessons

The economy's unravelling comes just as scraps from the boom begin to reach the nation's poorest, but those slim gains could be reversed

Ten-year-old Sonali sits on the baked mud floor of one of the open spaces of the village, grips a pencil tightly as if she fears it may dance away from her, and painstakingly writes spidery letters in a grubby exercise book. When she completes a line, she has a big smile on her face.

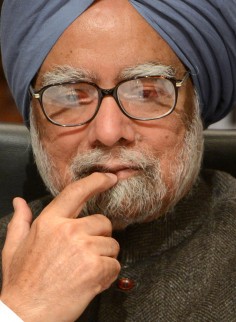

This is Paltoo ka Nangla in Uttar Pradesh state, just 55 kilometres from the Taj Mahal, that monument to love and power, and 205km from Delhi where Dr Manmohan Singh, DPhil (Oxford), wrestles with getting India's economy back on track.

Prime Minister Singh has protested that India is not facing a crisis. But those sceptical about the Indian miracle seem closer to the truth. From more than 9 per cent only two years ago, India's growth rate has dropped. The government was projecting 5.5 per cent for this year, but the latest quarterly figures show 4.4 per cent, leading economists to forecast that growth will be well below 5 per cent and may be a mere 3.7 per cent for the year.

Financial markets are distinctly underwhelmed by Singh's protests that all is alright. With the third highest current account deficit in the world, a government budget deficit of 9 per cent of gross domestic product and consumer price inflation of 10 per cent, India has big problems, exposed by promises that the US Federal Reserve would soon start tapering its US$85 billion a month programme of quantitative easing.

On every front, the government is in a bind. General elections are due next year, which makes it hard for politicians chasing the popular vote to take tough measures to cut the deficits. Sure enough, last week India's lower house of parliament passed a US$20 billion measure to provide cheap food for the country's 800 million poorest people.

That figure tellingly points to some of India's real problems. The supposed beneficiaries account for two-thirds of India's population. In spite of the recent spectacular growth, the rise of outsourcing, the forays by Indian companies abroad, with Tata buying Jaguar and ArcelorMittal becoming the world's biggest steel producer, the rise of the millionaires and billionaires in a booming prosperous middle class of 300 million people, many Indians have been left behind.

Economic theory says that if a country's currency depreciates, not least because of a heavy current account deficit, it offers opportunities to boost exports. Singh's and India's problem is that the import bill, especially for oil and gas, goes up immediately.

India's economy was never a juggernaut, as some had claimed, but a BMW or Lexus for the million at the top, a cheap Suzuki Maruti for the next 40 million, a two-wheeled scooter for a further 100 million, a bicycle for a further few hundred million and an overcrowded bus or their own two feet for most of the masses. Now, the wheels are falling off the Marutis and scooters, which were anyway stuck in traffic jams on potholed roads.

The government needs to spend more money and more wisely on too many essential things from basic education to basic infrastructure, but its budget is overstretched and spending is filtered through one of the world's most corrupt countries.

Paltoo is instructive. The last two years has seen the belated arrival of electricity and the privately run school, costing 100 rupees a month. Nearby cell towers have enabled mobile telephones and a handful of villagers have one, including a shopkeeper, also a new arrival, although his "shop" is little more than a hutch selling knick-knacks and snacks and school pens.

But this prosperity is thanks mainly to money sent back by men who have gone to Agra or Mumbai to work. Villagers complain that their wells are running dry, because of water mismanagement. If Singh has to raise interest rates to protect the rupee, growth rates will continue to fall, jobs will fail and the trickling progress of prosperity will dry up.

In Paltoo, with the school, a new door has been opened to the world for these very ordinary Indians. Does Singh have the wherewithal to keep it open?