China art auctions – a great money laundry

After a wobble a couple of years ago, China’s art market is hot and continues to be a hot topic. Art data from Artron showed sales in China exceeded the United States for the first time in 2010. Sales in 2013 were 57 billion yuan (HK$72.5 billion).

But it’s been a bumpy ride, with a major hiccup in 2012. The China Association of Auctioneers (CAA) and international art group Artnet reported 788 auctions in 2012 made Rmb29 billion – half last year’s figure.

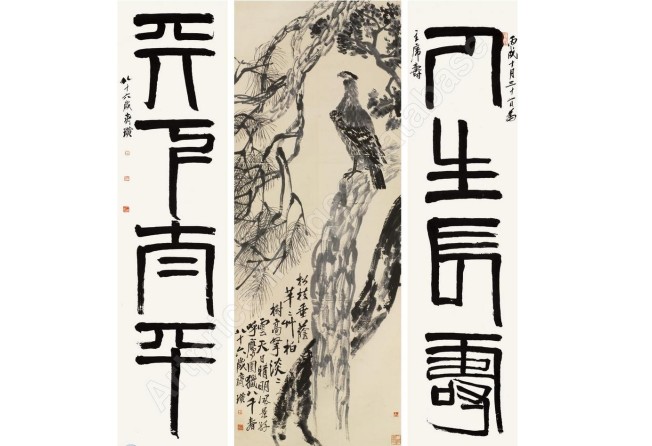

The 2012 -2011 wobble, according to the CAA, was due to “only half of the works offered at auction actually selling”. This can be attributed to many buyers questioning authenticity and refusing to pay. Eagle Standing on a Pine Tree, a 1946 ink painting by Qi Baishi, made a record $65.4 million in May 2011. But the New York Times noted the painting was still languishing in a Beijing warehouse two years later. The bidder had refused to pay up, doubting it was genuine.

As well as counterfeit concerns, Week in China explains that payment defaults often occur when bidders agree to sky-high valuations in an attempt to prop up prices for works by particular painters or artists that these “market makers” collect. Some auction houses look the other way as long as the (eventually aborted) sales make the market look strong. Pieces often get sold time and again.

Reuters noted in October that a Qi Baishi painting had gone under the hammer four times in a decade, with the price shooting from $30,000 to $794,000.

You’d think the general air of dodginess would spook buyers, but demand of Chinese art continues unchecked. The reason? “The price of Chinese art is really abnormal,” Jiang Yinfeng, a painter and art critic told the Worker’s Daily. “Art has become the best tool for money laundering and corruption.”

Roots in gift-giving

China’s gift-giving culture drives up prices. Demand is driven by businessmen buying artefacts as presents for officials. Fake or genuine, an artwork presents an opportunity to ‘wash’ a bribe, WIC explains. It’s not rocket science. A businessman gives a painting to an official, whose relative auctions it off. The businessman buys it back at an inflated price and the official pockets the cash. This leaves less evidence linking favour to bribe than handing over suitcases of cash. More sophisticated schemes exist but this is the general idea.

Real or fake?

It goes without saying that a clampdown on dodgy art deals will hit all players in the business, but no one really knows how much is real.

Questions of authenticity crop up time and again and are beginning to cast a shadow, but the market continues to expand. Not only do art sales attract much lower rates of tax than other business deals in China, but with no retail reference, their book value can be ratcheted up or down, depending who’s asking.

Two recent cases have caused red faces and backed Sotheby’s auction house into a corner. China art collector and major returner of artefacts to the Motherland, Zhao Tailai, also known as Chiu Tai-loy, is involved in a new controversy. Last February, WIC explains that he exhibited 15 paintings in Hong Kong by famous Chinese ink painter Fu Baoshi, but Fu’s granddaughter Fu Leilei challenged their authenticity.

“Anyone with very basic knowledge and experience in art authentication could tell at first glance these paintings were fake,” she told a CCTV programme. Zhao maintains they are the real thing, authenticated by experts. Then last week, Sotheby’s quickly sent out a press release, defending a scroll they sold in September, by Song Dynasty poet Su Shi.

The Shanghai businessman who paid US$8.2 million for it as “one of the greatest works of calligraphy, asked the Shanghai Museum to check. They said it was a forgery.

In spite of Sotheby’s producing a 14-page report insisting it’s an original, the buyer is now seeking other independent verdicts.

Elegant bribery

Now the issue of dodgy art shenanigans has caught the attention of the mighty Party’s Central Commission for Discipline Inspection. As well as the counterfeit element, they don’t like the art world being used as a conduit for officials to launder bribes.

Buying favours from officials with gifts of art has become so popular it’s spawned a new phrase: “yahui”, or “elegant bribery”. It even rated a mention in dispatches by China’s anti-graft watchdog last week, after wider investigations into corrupt cadres last year.

China’s discipline commission said it had received 1.95 million reports (up 49% from 2012) of corrupt behaviour. More than 180,000 Party members were disciplined, while at least 31 senior officials are under investigation or being prosecuted, reports WIC.

Jewellery and paintings popular currency

The biggest fish caught were senior bosses in the oil sector and at the economic planner, the NDRC. Enter one Ni Fake, the former deputy governor of Anhui province, who popped up when the China Discipline Inspection Daily, the corruption watchdog’s newspaper published his case.

Ni headed Anhui’s land resources in 2008 but apparently also served – without Party permission – as the chairman of the province’s jewellery association, reports WIC. The China Discipline Inspection Daily found that 80 per cent of the bribes Ni took were jade and paintings.

Once arrested, Ni told investigators that gemstones were “more elegant, more civilised and more meaningful when passed on to offspring.” Clearly a man of refinement and taste. More importantly, they were portable. “Jades and paintings offer investment value and easy storage,” Ni explained. “Insiders know you have such a hobby. Outsiders don’t know how much they are worth.”

The crafty cadre’s goodie collection was so large that he asked a business chum to build an exhibition centre to house his loot, to disguise his ownership, but Ni was caught before it was built. The discipline commission said inspectors also confiscated 90 paintings from his family.

Ni isn’t alone, there have been other examples. WIC reports that Qiushi, another high-level Party journal, commented: “senior officials letting such hobbies be known is as good as soliciting bribes publicly,” it claimed. “Ni Fake’s case is a stern warning for these officials.”

China Business News noted that it was unusual for Ni’s case to get so much air play – especially as he is still under judicial prosecution. They concluded the corruption watchdog was “pointing its sword” to deter further cases of yahui. The question is, once caught and confiscated, what happens to the loot and the proceeds?