Business successions that go awry are the stuff of soap operas and tabloids

In the next 20 years, as many as 500 wealthy families with US$2.1 trillion of assets – equal to India’s GDP – will face the challenge of succession planning, according to UBS’ forecast

Business successions: when they go bad, they are the stuff of soap operas and tabloids.

The strife between the heirs of the famous roast goose restaurant Yung Kee and the case of Nina Wang, wife of the still-missing tycoon Teddy Wang, and the fung shui master who looked to inherit the Chinachem fortune were the talk of the town in Hong Kong.

“Every business founder exits the business at one point, whether by design or default,” said Bernard Rennell, global head of family governance and family enterprise succession for HSBC Private Banking. “Better it be by design.”

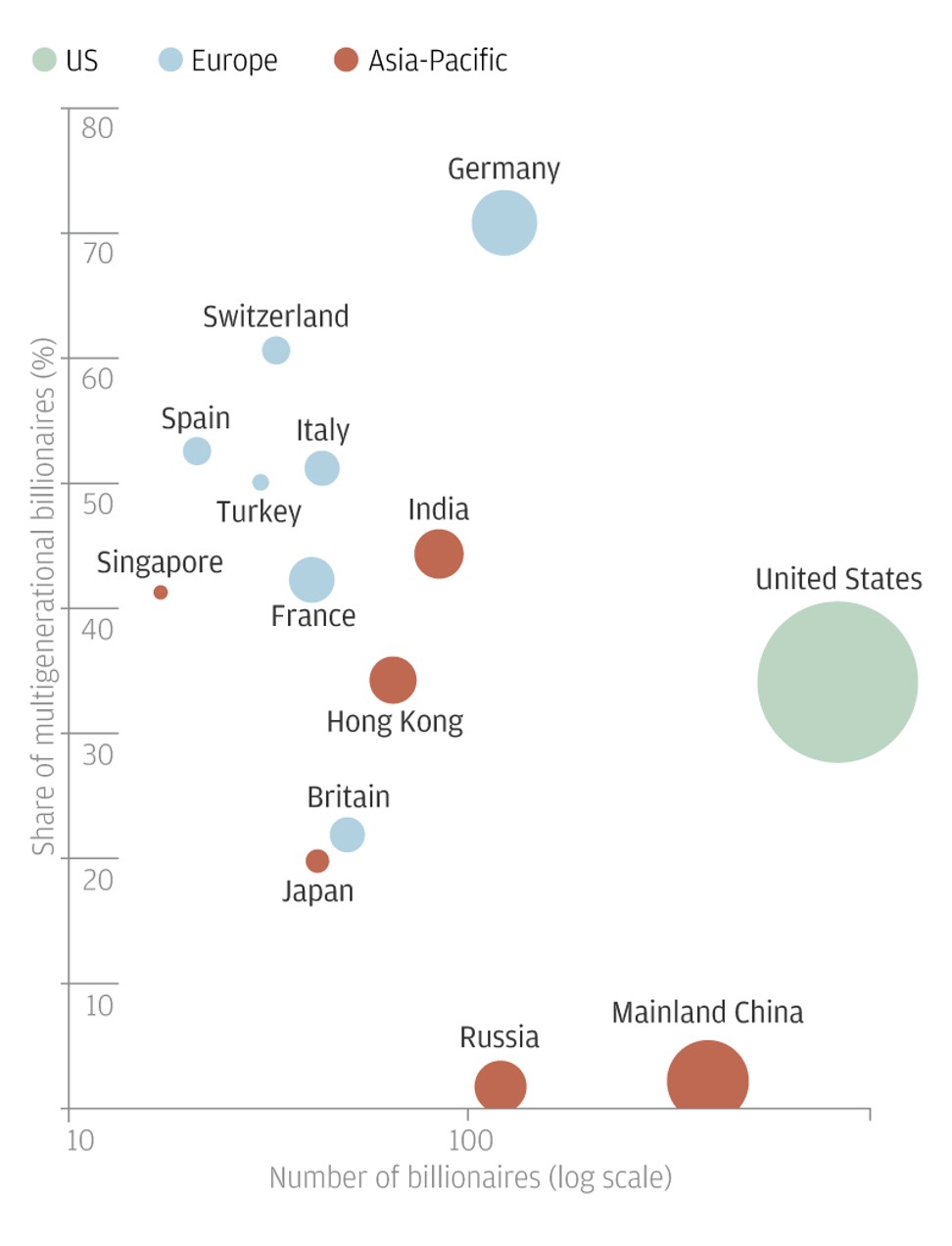

“In the next 20 years, we expect a US$2.1 trillion shift in assets as around 500 families face the challenge of succession ... This is massive. It’s the current [gross domestic product] of India,” he said, citing a 2016 UBS report with 20 years of data tracking 1,400 billionaires, accounting for 80 per cent of global billionaire wealth.

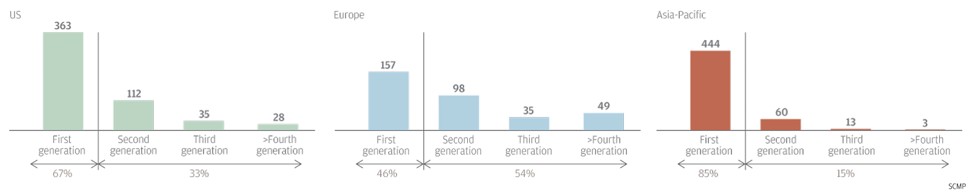

In Asia-Pacific, 85 per cent of those billionaires who would soon face that generational shift would be first-generation, Landolt said.

So, when should company founders start to think about handing over the reins? As early as possible appears to be the consensus.

“The best time to do it is when relationships are good, but families are often only talking about it when things are broken,” said Woo Pat-nie, KPMG’s expert on family businesses. “The business cannot thrive if the family dynamics are bad.”

As a general rule, research indicates there is roughly a 30 per cent survival rate for family businesses in the second generation, a number that goes down to 12 per cent in the third. Only 3 to 4 per cent usually make it to the fourth generation and beyond.

“That’s usually driven by family members, and not really driven by market change or big disruptions like technology,” Landolt said.

Businesses can cope with market change and disruptions if the family is willing and ready to support trying new things. “If your family is not organised, your mindset will not be into developing or bringing your business as well into a path of change,” Landolt said.

“Europe tends to know about [succession] more because family wealth has been there longer. There’s quite a lot of activity in Australia as well. People are getting there in Hong Kong and [mainland] China, but generally it’s not as common in the market,” Woo said.

However, Landolt predicts greater action in the coming years, given that the mentality of families has shifted from “we have to plan” to “why didn’t we start planning 10 years ago?”as the death of company founders becomes imminent.

“We see this actually across Asia. This might be why the topic is so big currently in Asia as a lot of those matriarchs and patriarchs are in a similar age,” he said.

While details differ for each family, there are two key things that Landolt believes are necessary for the business to succeed.

One is keeping the ownership within a close group of owners. “Avoid, in your fifth generation, having 200 family owners – and not having a structure around it,” he said.

He advises those in countries where they cannot put ownership under a legal structure on setting this out in a shareholders’ agreement to create an internal share market and encourage family members in a way to sell out to other family members.

Families can put in place another structure where members are not part of the business anymore but can get support for a new business or some kind of dividend without necessarily being part of the ownership.

The other key action is to clean up corporate governance.

“Even if it’s family-owned, it has to be very clear who has which role, who gets which benefit,” Landolt said.

The documents are about managing families’ expectations and knowing where each member of the family stands.

Not all businesses are passed from generation to generation. In the US, it was more of a model of serial entrepreneurship, Landolt said.

For people who do not plan to hand their business down to their children, they might learn more from the experience of Angelo Venardos, founder of Singaporean trust group Heritage Trust Group. He sold his business to international trust and corporate services company Equiom in 2016.

“It’s the little things that one would find hard to let go of,” Venardos said. “How are you going to feel moving out of the office you’ve been sitting in for 16 years?”

It was not uncommon for families to bring in counsellors to deal with the issue of dynamics, Woo said.

History has a litany of examples, whether it is sibling rivalries, fights for control or disagreements between generations, even in Hong Kong with the experiences of gaming tycoon Stanley Ho Hung-sun or the example of the Yung Kee restaurant.

“It may sound illogical, but logic doesn’t always trump emotion,” Woo said.

For EY’s Ringo Choi, a variety of factors will determine whether a company decides to plan for a replacement. One is the growth rate of the company and how the market share or profitability compares to that of competitors. If the company is lagging significantly, it might be time to consider change. Another is whether the current management is able to keep up with the pace of development in the field.

“The world is changing so fast, the internet, [financial technology] and other technologies. They change the business world very fast, and so that’s why you can see a lot of new management teams need to come out and adjust to the new environment, propose new ideas to maintain the growth engine of the company,” Choi said.

With all this said, it is still early to say how much planning will be needed to mitigate the so-called three-generation curse. Even now, the average lifespan of a company is about 30 to 40 years.

Just because a company does not have a succession plan does not mean it is automatically doomed to be another footnote in history.

“It’s an exaggerated statement if you say a company that does not plan succession will die all of a sudden,” Choi said.

When Gianni Versace was murdered in front of his Miami mansion in 1997, the family had no formal succession plan in place, but his sister Donatella managed to turn around the fortunes of the brand.

But like the others, Choi does warn against family feuds. In the long term, the company will lose a lot of momentum and problems may surface if the company becomes heavily involved in political jockeying or if family members are set against one another.

“Then the company may slow down or come to a standstill. With litigation, the company will be severely affected,” he said.

(These are excerpts of an article published in the May issue of The Peak magazine, available by invitation and at selected news stands.)