Planned joint maritime security exercise shows Asean can lead

Mark Valencia hails the maritime initiative, given the rancour among nations on South China Sea

Asean defence chiefs agreed earlier this month to undertake a joint maritime security exercise in the strategic Malacca Strait next year. While that may not seem exactly earth-shaking, it would be a sharp break with the past practice of eschewing formal Asean-wide security exercises. Indeed, it is a bold initiative that sends strong signals to extra-regional powers that the Association of Southeast Asian Nations can still be a player in the security arena.

The timing is auspicious. Asean is currently struggling to present a united front vis-à-vis China regarding the details of a code of conduct in the South China Sea. In the bigger picture, members are trying to avoid being split by the US-China contest for their "hearts and minds" and to maintain Asean centrality in security architecture for the region.

Asean, formed in 1967 as a pro-West capitalist bulwark against the spread of communism, emphasising enhanced economic co-operation, is trying to transform itself into a "political-security community" by 2015. Many in the West think this is a bridge too far. Indeed, Asean has long been dismissed as nothing more than a talk shop. Some predict that US-China rivalry will dominate regional political affairs, increase instability and erode the grouping's political and security centrality.

Cracks are already beginning to appear. Supposed neutrals Indonesia and Malaysia are now leaning towards the US. Singapore, as a US strategic partner, and the Philippines, as a US ally, are already there. Thailand is a holdover US military ally from another era. But, in a pinch, it may well bend towards its powerful Asian neighbour. Vietnam has been very public in its attempts to draw in the US as a balancer to China. And the US has even made political inroads in Myanmar - before now a staunch China supporter.

But this Western "invasion" has not completely erased the ancient influence of Chinese culture and its diaspora - and the respect for, and fear of, China. Many Southeast Asian countries take the long-term view: China will always be there. Their valid concern is that US influence may eventually recede like the outgoing tide, to be replaced by a Chinese storm surge.

Asean was already divided on the South China Sea issues. Non-claimants Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Thailand seem to have a preference for engaging China through a "low-key approach". Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam have rival claims vis-à-vis China - and each other. The latter is significant because China has played on those differences. The Philippines and Vietnam oppose China's claims while, historically, Brunei and Malaysia have been more low key. Brunei may now be going its own way and Malaysia's position is becoming increasingly ambiguous. Indonesia and Singapore have attempted to play mediating roles between China and the Philippines and Vietnam - while maintaining Asean unity.

A fundamental question facing Southeast Asia is whether it can resist these new outside influences - currently manifest in the South China Sea disputes - and sustain its own centrality in maintaining regional security. Or will the region once again be riven, manipulated, and tortured by a political struggle between outside powers?

The Malacca Strait joint exercise is a U-turn from the 2012 debacle when Asean publicly split over South China Sea issues and for the first time failed to agree on the wording of a communiqué at the end of its annual meeting.

That nadir makes the security initiative all the more remarkable. Malaysia and Indonesia have for years fiercely guarded their sovereign rights in the strait. To now put aside suspicions sends a signal that Asean can overcome national differences, remain unified and manage its own security affairs - at least in the strait. It is a wise choice of location; any exercise in the South China Sea would have raised other problems and antagonised China.

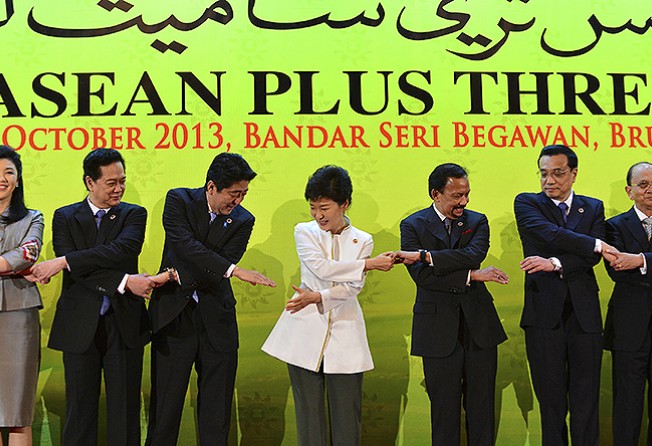

Nevertheless, outside powers such as China, India, Japan and the US are likely to want to participate, given their geostrategic interests. In the statement announcing the initiative, Asean defence chiefs also recognised that "the early conclusion of a code of conduct in the South China Sea is crucial to maritime security and to a stable security environment in the region". Linking the code conceptually with the initiative is a clever step forward for Asean unity.

Of course, to pull this off politically, members must overcome or at least paper over significant differences not just in managing the security of the strait, but on broader security issues. Although something could still derail the exercise, it could be a first step in a conceptual sea change on regional security. If Asean can build on this initiative, it may well be what Indonesia's Foreign Minister Marty Natalagawa hoped for during the recent depths of Asean disunity - "a groundbreaking, perception-changing, paradigm-shifting event".

Mark J. Valencia is an adjunct senior scholar at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, Hainan