From Shanghai, lessons of social integration for Hong Kong

Paul Yip and Yuan Ren say integration is vital for any city with a large population of migrants and visitors. As such, Shanghai's focus on providing opportunities for all is noteworthy

Hong Kong is still ranked the most competitive among the 294 Chinese cities surveyed for the latest Chinese Academy of Social Sciences "blue paper", doing well in most of the indicators, including in business, harmony, ecology, sustainability and culture. However, Zhuhai has overtaken us as the most liveable city, due to the high cost of housing and limited living space in Hong Kong. We also lag behind Beijing, Shanghai and Nanjing as a knowledge- and information-based economy.

This sends a timely warning to Hong Kong, especially if we consider its aspiration to be a "world city" like London, Paris, New York and Tokyo. Hongkongers will certainly not be satisfied with being seen as just one of many cities in China.

There's no doubt that Hong Kong faces acute challenges, including limited living space, an overcrowded environment and disharmony among locals, visitors and migrants from the mainland.

Hong Kong's population is ageing fast; by 2030, it is expected that 25 per cent of the population will be 65 or above. We need more young people to rejuvenate our population and maintain our socio-economic development.

Despite a very low fertility rate of about one child per woman, Hong Kong's population is supported by 150 mainlanders entering the city each day through the one-way permit scheme. Allowing them in not only facilitates family reunions, it has also provided a steady source of manpower for some sectors suffering shortages, especially in catering, security and elderly care.

At the same time, we face difficulties in meeting the demands of the 50 million visitors a year, a number which has already exceeded Hong Kong's capacity to cope. The local leisure and shopping scene has been undergoing continuous change in reaction to the needs of mainland visitors. More pharmacies, watch and jewellery shops have sprung up, dominating the landscape. Business rentals have been driven up and subsequently the prices of most things have gone up, too.

The general public (save landlords) have not benefited from the growth in visitor numbers. The contribution of tourism to the economy - and the local community - has been grossly exaggerated. Even though it might account for the estimated 3-4 per cent of growth in gross domestic product, the benefits don't outweigh the costs to the whole community. In other words, the books simply don't balance. For the majority, quality of life has not improved; for many it is declining. Yet it's not the fault of the visitors. Indeed, sometimes they are the victims of irresponsible local practices, too. The recent dispute over a mainland child urinating in a Mong Kok street is a reflection of the conflicting sentiment in the community about the effects of the large numbers of mainland visitors.

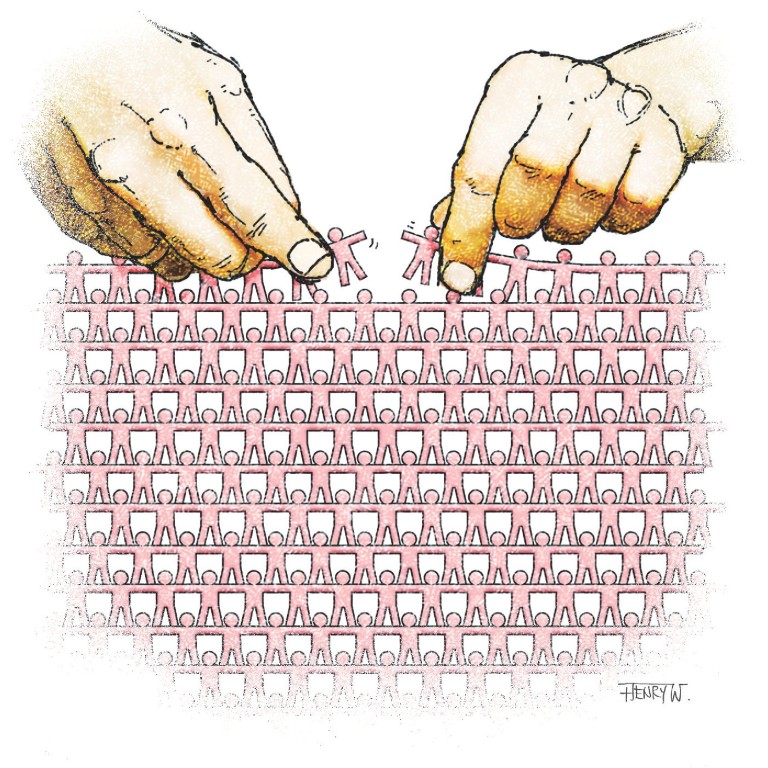

Inner-city conflict between new arrivals and locals is common elsewhere, too, from North America and Europe to Africa and Latin America. Urban migration is a process; conflict and integration are two sides of it. Sometimes, conflict can be a good thing in social integration, as it allows locals and migrants to better understand their own interests, can lead to exchanges and contact, and help create new social structures. Migrants and local residents are likely to achieve social integration through mutual exchanges.

However, conflict can, of course, have negative effects. Locals often resent migrants, as they see them taking employment opportunities and social welfare. Distrust is also common. The kind of riots by migrants in France and Italy, in retaliation for being mistreated in the community, is not uncommon.

Shanghai's experience provides a useful study for us; it, too, faces problems related to conflict between migrants and locals. Shanghai's population has reached 24 million, including a massive migrant population of almost 10 million.

Such mass migration has brought great pressures to bear on the city's development. Yet, over time, many migrants have gradually integrated into the city. An increasing number have stable jobs and relatively high income and education levels, resulting in them becoming part of the city's emerging middle class. They have begun to establish a sense of belonging and social identity. Second-generation migrants are accepted more readily and seen in a positive light.

Shanghai has shown how social integration can be nurtured. Living together in new high-rise blocks, locals, migrants and international migrants are showing tolerance and acceptance, embracing diversity and openness. Certainly, Hong Kong and Shanghai are unique, but for successful integration and development to occur, local residents and migrants in both cities need opportunities in education and work.

If the basic infrastructure is in place, everyone can grow and there will be no need to accuse others of stealing opportunities. Providing opportunities for upward mobility to local young people and improving the quality of life for locals are important. Hence, we should not only look at ways to provide the necessary infrastructure to cater for visitors, we must also enhance development of the city.

To be effective, policies should focus on further improving opportunities in education, especially for post-secondary students, by providing financial support and the appropriate training, while enhancing welfare support for those in need, with the aim of equipping them with the skills to support themselves.

We also need to develop a culture of innovation, and expand urban space for all, to allow the progressive integration and social inclusion of migrants. Conflict is not inevitable.