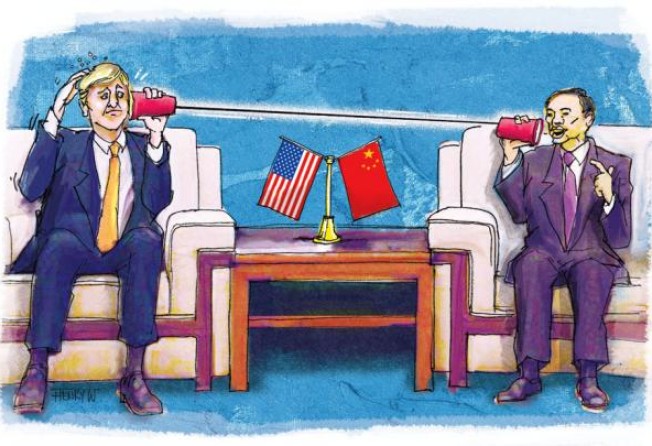

China must leave its foreign policy to the experts

Lanxin Xiang says China’s diplomacy must be conducted by those with strategic vision, rather than the technocrats who have fumbled over the past decade, to set a policy that inspires trust

For years, China's leaders have been struggling to find a new concept to reset, if not redefine, the Sino-US relationship. So far, they has come up with only vague ideas such as "peaceful rise" and, more recently, "a new type of international relations between major countries".

With the re-election of Barack Obama as US president and the transfer of power in China to a new generation, one of the biggest challenges facing Obama will be finding a strategic and economic role for the United States in Asia that is acceptable to its strong network of allies and friends without alienating the Chinese.

The biggest challenge facing the new Chinese leadership in the region is how to repair relations with China's neighbours, and its image. In the past decade, Chinese foreign policy cannot be called a success, for two reasons.

First, the leadership has been obsessed with the search for an overarching concept to guide foreign policy, but no such concept works or even sticks. The early years of the Hu Jintao-Wen Jiabao regime witnessed the quick rise and fall of the idea of "peaceful rise". As soon as the Americans countered with the "responsible stakeholder" concept, outlined by then deputy secretary of state Robert Zoellick, "peaceful rise" fizzled out, for China was hardly ready or willing to take up responsibilities as a great power. Indeed, China always claims it does not want to be a great power.

Later, Hu came up with the concept of "the harmonious world". This time, the confusion was even more evident. The real world is far from harmonious. To extend a political slogan at home - "a harmonious society" - to the anarchical world system not only looked silly, but also seemed to demonstrate China's hidden agenda of "harmonising the world" through efforts to change the rules of the game.

Besides, the leadership has failed to maintain domestic harmony, as widespread corruption and social tension have pushed China closer to revolution. Indeed, Chinese bloggers have ended up using the phrase "to be harmonised" to indicate web censorship.

More shockingly, in the past three years, China has somehow managed to squander its remarkable achievement in establishing good rapport with its neighbours, losing a reservoir of goodwill that several generations of leaders had accumulated over more than six decades. The goodwill was founded on the smart and effective "periphery policy" (zhoubian zhengce). Its loss provided fertile ground for the US to successfully build a containment strategy in Asia and the Pacific, at minimal diplomatic and material cost.

The diplomatic failure of the past 10 years has taught us at least one lesson: China should never announce any concept that is vague and confusing. For example, a concept such as "core interests", when applied unwisely to disputed territories, could trigger enormous suspicion of Chinese intentions.

Therefore, the latest Chinese proposal for a "new type of international relations between major countries" is viewed by Washington in two ways: first, the goal appears to be for China to take a bigger share of power, but not responsibility; second, it may be a scheme to undermine Washington's new Asian strategy. Many in Washington fear that, rather than share power, China really wants to unravel America's alliances in Asia.

The Chinese claim they want to foster "mutual respect" and "win-win" conditions, but it is not convincing to talk only about the desired result without specifying how to achieve it. Worse, it is vague about what a "major country" is. If the Chinese instead use the concept of "great power", then the logic is comprehensible: China is proposing to the US to reset the bilateral relationship to avoid the traditional trap of great power rivalry, especially during the process of structural change of the international system.

Great power status comes, above all, with responsibilities. But the official Chinese translation of the term "great power" is in total chaos. The foreign ministry describes a "new type of relations between major countries"; Xinhua uses "big powers"; still others, even more absurdly, use "big countries". The reason for this chaos is clear: to avoid the connotations related to the modern Chinese history of national humiliation.

Since the Opium war in the 19th century, "great power" has been translated as "power in match" ( lieqiang), which was exclusively used to describe the imperial powers that invaded and humiliated China. So, Beijing now chooses the more neutral term of "major country". But by doing so, it fails to communicate the right message to the Americans.

The right message should be: a rising China will not challenge and undermine the leadership position of the US, and will increasingly take upon itself more international duties. The precondition is, of course, that the US stops its silly containment policy. As Xi Jinping's put it, "at a time when people long for peace, stability and development, to deliberately give prominence to the military security agenda … is not really what most countries in the region hope to see".

Any overarching concept without a clear definition is subject to wrong and vicious interpretations. The new Chinese leadership differs from the previous ones in its education background, personal experience and strategic outlook. Most of its members were trained in the social sciences and humanities, unlike the engineers who have run China for the past 20 years, starting with Jiang Zemin .

As it turned out, the engineers were a perfect match for a foreign-policy elite dominated by language specialists, to whom instant results is the only measure of success. One should not expect them to have a long-term strategic vision.

The new leadership should realise that, to avoid future diplomatic disasters, this type of "diplomat" must be pushed back to where they belong - sitting in the background and doing their technical work - and not be allowed to develop strategic plans. Indeed, the reform of China's foreign policy and national security structure is no less urgent an issue, for foreign policy is too important to be left to language technicians.

Establishing a political appointee system to allow those who have the confidence of the top leaders to conduct foreign policy might be the most effective way out.

Lanxin Xiang is professor of international history and politics at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva