Does China model herald a post-democratic future?

Kevin Rafferty cautions that there are deep failings in a 'Beijing consensus'

The sound of squabbling from the schoolyard brawl of the Washington DC Political Academy must be music to the ears of those who say that American democracy always was a fraud and is now broken.

The contrast between the mindless partisan fighting in Washington and the smooth way that the changing of the guard is now going on in China has emboldened some people to assert that we have seen the global future and it is the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party.

The problem will come if people start believing this. Well-connected Shanghai venture capitalist Eric Li certainly does. In his recent article on the virtues of the Chinese system, in Foreign Affairs, Li claims that it is the supreme meritocracy that rewards proven talent: "A person with Barack Obama's pre-presidential professional experience would not even be the manager of a small county in China's system."

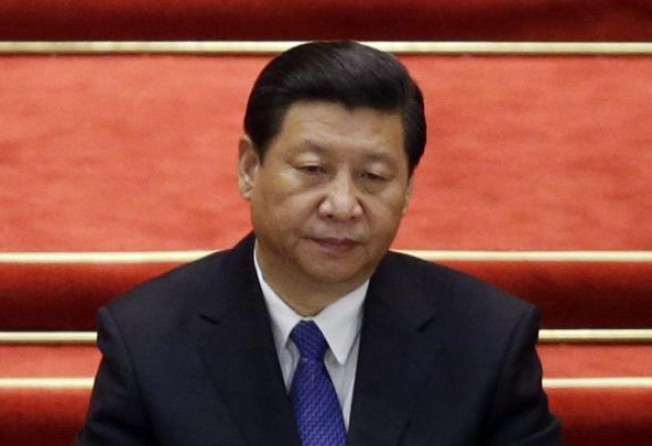

To rub the message home, he contrasts Obama with China's new leader Xi Jinping: "By the time he made it to the top, Xi had already managed areas with total populations of over 150 million and combined GDPs of more than US$1.5 trillion."

He asserts that, despite daunting challenges, "China will continue to rise, not fade. The country's leaders will consolidate the one party model and, in the process, challenge the West's conventional wisdom about political development and the inevitable march towards electoral democracy. In the capital of the Middle Kingdom, the world might witness the birth of a post-democratic future".

Li skates daringly over the historical record, citing the land collectivisation of the early 1950s, the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution as proof of the Communist Party's "extraordinary adaptability". "The underlying goal has always been economic health," claims Li, "and when a policy did not work - for example, the disastrous Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution - China was able to find something that did: for example, Deng's reforms…"

Of course, he plays fast and sometimes very loose with inconvenient facts, such as the role of the princelings, the ways of measuring popular support for the party and the implications of the rise and fall of Bo Xilai for the rule of law and indeed for the party.

Corruption, Li admits, could "seriously harm" the party's reputation, but "it will not derail party rule anytime soon." He claims that China today is less corrupt than the US when it was going through industrialisation 150 years ago, and less violent.

It is also less corrupt, according to Transparency International, than some electoral democracies such as Greece, India, Indonesia, Argentina and the Philippines.

Given the mess in the US, it may be tempting to assert the superiority of the Chinese model. But there are deep flaws in the model, many to do with the age-old question posed by Juvenal, as to who guards the guards. Some of Li's suggestions for improvements verge on democracy. Why not go the whole way? Are the Chinese people not as ready and intelligent, mature and aware as Americans or Indians or any Europeans, to decide their own leaders?

The underlying problem with the so-called "Beijing consensus" is that it is very much Chinese and very little consensus, whether talking about economic or political systems.

Politically, China's Communist Party rule is sui generis, the culmination of victory in a long and violent struggle. No doubt many dictators would like to claim the model as their cover. The problem for the world is that there is a growing nationalist edge to the Chinese political view, sometimes through a fog, dangerously.

Kevin Rafferty is a political commentator