China could learn from Singapore's public housing model

Winston Mok says China could set up a national housing board similar to Singapore's to drive its ambitious plan for affordable urban housing, rather than rely on reluctant local officials

Even with the small dip after strong control measures, housing prices in Hong Kong remain near a historic high. With its property among the most expensive in the world, Hong Kong has long grappled with the problem of housing affordability. The government relies on land sales as a major source of income and lacks a coherent housing strategy. To effectively address it, a co-ordinated programme should have been put in place more than two decades ago.

Yet mainland China has worse housing problems than Hong Kong. But it is not too late to fix it. Only about 10 per cent of mainland urban housing is public housing, compared to Hong Kong's 50 per cent. In contrast, more than 80 per cent of Singaporeans live in Housing Development Board flats, mostly owner-occupied. Through this public housing scheme, Singapore has achieved the highest home ownership rate in Asia - at 90 per cent, according to the latest figures - contributing to its social stability.

Expensive housing is one of the obstacles standing in the way of mainland China's urbanisation. Using the housing price-to-income ratio as an indication, mainland cities have a ratio of 16 (comparable to Hong Kong's 18, much higher than Singapore's 6), among the highest in the world.

Nobel Prize winner Mo Yan, who originally came from a farming village, half jokingly said that he would like to use his sizeable prize money to buy an apartment in Beijing, but given the high prices, he could afford only a modest apartment outside the downtown areas.

China has introduced a series of measures to cool the housing sector. From the beginning of this month, a 20 per cent capital gains tax has been levied on second-hand property transactions in many cities. As with many earlier measures deemed ineffective, this latest tax is seen by some as counterproductive in the long term. These control measures restrict demand without increasing supply.

Only ample supply will keep prices affordable. Therefore, the fundamental solution is a significant public housing programme, which would increase overall supply and reduce demand for commercial housing at the same time.

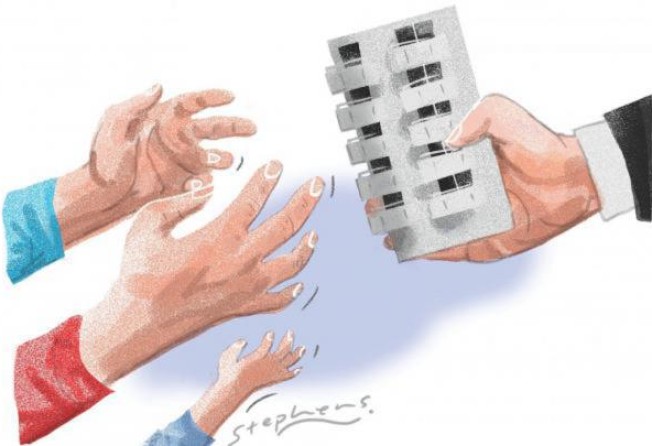

While China has embarked on an ambitious programme of building 36 million public housing units in the five years from 2011, the target is unlikely to be met if left in the hands of local governments. After a surge in 2011 and peaking in 2012, central government subsidies for public housing have declined this year, heralding a potential slowdown of the programme. Since it began, the number of new starts has declined year by year, and fewer than 5 million units have been completed per year. At this rate, by 2015 the number is unlikely to exceed 25 million.

Importantly, these units are reserved for local people and not migrant workers, whose access to crowded tenements is squeezed as land is cleared for new apartments. Public housing is bad business for local governments, which like to maximise land prices to increase their revenue. It reduces demand of land for private housing, thus depressing both prices and volumes. Since public housing is seen by local governments as against their economic interests, they will find creative ways to "manage" the central government and compromise the programme's effectiveness.

To implement an effective public housing programme, China could set up a centralised housing development board. After a transition period, this board would be responsible for developing public housing nationwide. Regional and local branches would report to the headquarters.

World-class professionals should be appointed to lead it and be held accountable to deliver against well-defined performance targets. The board's performance, reported on its website, could then be monitored by other government or statutory bodies. In addition to the timely completion of apartments in accordance with quality standards, the performance of both the national housing board and the local governments should be measured on whether the units are assigned to the intended occupants.

China need not go as far as Singapore's model, which is dominated by public housing. Beijing could start with a more modest target of 30 per cent public housing in cities, to be gradually adjusted over time and by region, based on market signals. Hong Kong's level of 50 per cent could be a longer-term, although not necessarily final, goal for some cities.

The supply of new public housing may be linked to housing prices. The higher the prices in a city, the higher the level of public housing that will be provided; this could help prevent runaway prices.

Effective urbanisation should be based on providing affordable housing to new urban residents. An effective owner-occupier public housing programme will boost domestic demand, increase gross domestic product and improve social stability.

Singapore's public housing programme is the most visible part of its social architecture. In its attempt to emulate Singapore, China could consider adapting this highly successful programme for its use.

Winston Mok is a private investor, a former private equity investor and McKinsey consultant. An MIT alum, he studied under three Nobel laureates in economics