Academics denied their place in debate on Hong Kong

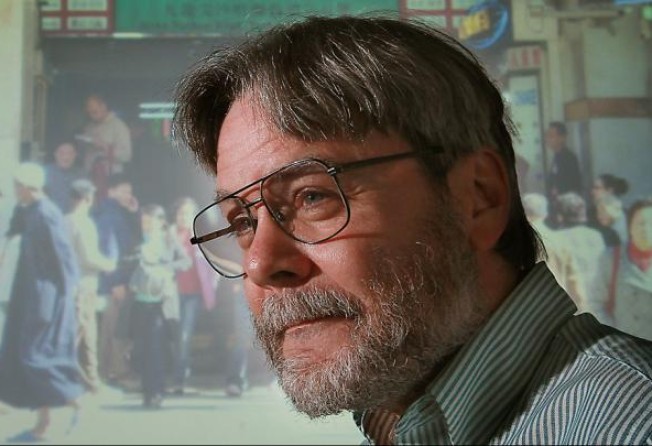

Gordon Mathews says biased ranking exercise favours research in English

Hong Kong universities are now gearing up for the Research Assessment Exercise, imported from Margaret Thatcher's Britain. Academics are required to choose their four "best" publications over the past six years; these will be evaluated by committees of experts, who will then rank different academic departments as to their research productivity. Highly ranked departments will get more money; poorly ranked departments will get less money, with implications for individuals' jobs and futures.

At first glance, this may seem entirely reasonable. Academics in Hong Kong are well paid compared to many of their overseas counterparts. Why shouldn't their performance be measured? Why shouldn't the ivory tower be subject to the same kinds of performance reviews as any other profession?

It indeed should, but there are significant problems here. Because the committees of experts judging these exercises are more than half foreign, publications in Chinese don't count. (This is denied in the guidance notes for the exercise, but is indeed the case, as many academics here can attest.)

In the sciences, academic writing is typically in English; in the arts and social sciences, it often is not. Thus, a historian or sociologist who writes a book about Hong Kong had better not write it in Chinese. Most people in Hong Kong read Chinese, not English. But for the assessment, this doesn't matter.

Beyond this, if this historian or sociologist writes an article about Hong Kong, it had better not be published locally, but only by a prestigious Anglo-American journal, most of whose readers will care little about Hong Kong. Typically, the experts judge "best" publications on the basis of the publisher, since they haven't time to actually read the massive amount of submitted work. Prestigious Anglo-American publishers count for much; Asian publishers, particularly Hong Kong ones, count for little.

Unlike the hard sciences, which are more or less universal, in the arts and social sciences Anglo-American publishers publish work of interest to Anglo-American audiences, and Asian publishers publish work of interest to Asian audiences. Thus, academics in the arts and social sciences here, needing to publish overseas, are pushed into writing articles dealing with Anglo-American theories rather than articles that are useful for understanding local issues.

This directly affects the role that academics can have in contributing to Hong Kong. The Research Assessment Exercise makes local research, local publication and local impact irrelevant. The learned men and women who comprise its expert committees do not have this intent, but the effect of their efforts is to render academics no more than mute technocrats instead of public intellectuals.

If I were a Chinese official in Beijing, I would be very happy that the exercise keeps Hong Kong academics publishing books and articles in distant places that few people read, rather than engaging in public debate through their research and publications on Hong Kong.

The solution to this problem is to take local research and publication much more seriously, and to have a far broader mode of making judgments as to research excellence. But this won't happen, because Hong Kong higher education is so obsessed with international rankings.

This makes Hong Kong humanists and social scientists into technocrats and bureaucrats, and makes Hong Kong universities increasingly resemble those of Singapore and mainland China.

Given the increasing thrall of the Research Assessment Exercise, I despair at what the future may hold for my junior colleagues, for Hong Kong universities, and indeed for Hong Kong at large.

Gordon Mathews teaches anthropology at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and wrote Ghetto at the Centre of the World: Chungking Mansions, Hong Kong