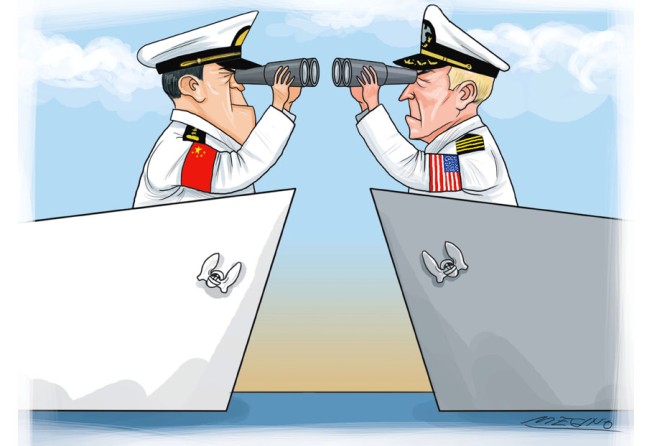

China and US must agree on rules for waters in exclusive economic zone

Mark Valencia says arguments about permitted naval activities in a country's exclusive economic zone are causing Sino-US tensions at sea, and they must be resolved soon to avert a conflict

Reports surfaced last month that Chinese vessels "harassed" the US Navy ocean surveillance vessel Impeccable in June, in what the US Navy claims are "international waters" about 100 nautical miles from Hainan . However, there has been no confirmation of the incident from either side.

The last time such an incident occurred was in March 2009, when the US protested vigorously and eventually sent a guided missile destroyer to escort the sub-hunting Impeccable. There may have been other incidents since then, but none has been reported, and some analysts assume the two sides had reached a modus operandi that avoids such dangerous encounters.

There has been quite a lot of second-guessing about the latest incident. If it occurred at all, some say it would represent a more aggressive Chinese stance against US close-in surveillance. But the commander of the US Pacific Command, Admiral Samuel Locklear, interviewed shortly before news of the incident surfaced, played down any possible provocative Chinese behaviour. He said that "in areas that are close to the Chinese homeland … we have been able to conduct operations around each other in a very professional and increasingly professional manner".

China's defence minister, General Chang Wanquan , met his US counterpart, Chuck Hagel, in Washington this month and they announced steps to improve military-to-military relations. However, Guan Youfei , foreign affairs spokesman for the Ministry of National Defence, complained about America's stepped-up, close-in surveillance, explaining that "any country would feel uneasy and threatened under such high-frequency reconnaissance". Earlier, Chang also warned that "no one should underestimate our will and determination in defending our territory, sovereignty and maritime rights".

What is strange is why, in the run-up to this important meeting, either side would risk precipitating an incident, unless it was part of a purposeful strategy.

In the June incident, the Chinese warned the US Navy vessel that it was operating illegally and that China had not granted permission for it to be there, according to reports. This gives a clue as to the differing positions that underlie these incidents. As Admiral Locklear said: "The US position is that those activities are less constrained that what the Chinese believe."

The Impeccable's mission is to use low-frequency sonar to detect and track undersea threats - enemy submarines, mines and torpedoes. China argues that the collection of such data is a "preparation of the battlefield" and thus a threat to use force - a violation of the UN charter and not a peaceful use of the ocean, as required by the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. China would presumably argue that its vessels were simply trying to stop the Impeccable violating international law and domestic law.

China is among some 166 nations that have ratified the 1982 convention. The US has not, although it maintains that most of it is binding customary law. However, customary law is constantly evolving based on state practice, as are the meanings of specific terms used in the convention.

Accordingly, there are several problems with the Pentagon's position on the incidents. First, there is no such thing as "international waters". According to the convention, there are internal waters, territorial waters, the exclusive economic zone and the high seas, each with its own regime regarding freedom of navigation. "International waters" is a term used by the US Navy to indicate areas where it thinks it has unconstrained navigational freedom. The term is imprecise and confusing and its use should be discontinued.

The legal underpinnings of the US position are also ambiguous. China maintains that the US action comes under the marine scientific research provisions of the convention and it has not given the US the required consent. However, the US distinguishes between marine scientific research, which requires consent, and hydrographic and military surveys, which are mentioned separately in the convention. The US maintains that the latter do not require consent, and are an exercise of the freedom of navigation and "other internationally lawful uses of the sea" protected by the convention.

Critics of the US position point out that collection of data for military purposes may also, unintentionally or otherwise, shed light on resources in the area, over which China has sovereignty per the convention. They also say a country that has not ratified the convention has little credibility interpreting it to its advantage.

The convention says that "the deployment and use of any type of scientific research equipment in any area of the marine environment shall be subject to the same conditions … for the conduct of marine scientific research in any such area". That would seem to tip the argument in China's favour.

The real issue is, of course, China's expanding blue-water navy capabilities and its new submarine base at Yulin, Hainan. Obviously, it wants to protect its "secrets" in the area, including the activities and capabilities of its submarines and the morphology of the sea bottom. And, just as intently, the US wants to know as much as it can about both. Thus, such incidents are likely to be repeated and become more dangerous.

Sooner rather than later, an agreement will be needed on a set of voluntary guidelines for military and intelligence-gathering activities in foreign exclusive economic zones and on definitions of permitted and prohibited conduct there. These would help avoid unnecessary incidents without banning any activities outright.

Specific guidelines have been proposed by a group of international experts meeting in their personal capacities over several years. The most relevant would be an obligation to use the ocean for peaceful purposes only, and refrain from the threat or use of force, as well as provocative acts. However, the US has rejected all such guidelines - voluntary or not. It may be time for it to reconsider its position.

Mark J. Valencia is a visiting senior scholar at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies in Haikou